(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Score one for the activists in shale. Yet there is so much more to do.

The Rice brothers have prevailed in their battle for the board of EQT Corp., the largest U.S. producer of natural gas. Toby and Derek Rice sold their company, Rice Energy Inc., to EQT in 2017. While the marketing of that deal left much to be desired (see this), the rationale of marrying up two big Appalachian gas positions was sound enough. Two years on, however, there is little evidence of EQT making the most of it. Instead of reaping the fruits of a vaunted $2.5 billion of synergies, a company valued at $11.3 billion bought another one for $6 billion and is now worth about $4 billion. Even adjusting for almost $9 billion of disposals along the way, that’s poison for shareholders and catnip for activists.

EQT embodies much of what ails the exploration and production sector in general. Investors no longer buy the idea that oil prices, and especially natural gas prices, will inevitably rebound. With that optionality discounted away, the only reason to own any of these stocks is if they can demonstrate more intrinsic value, chiefly by cutting costs, reining in capex, and generating positive free cash flow to pay out. EQT did actually deliver roughly $470 million of the latter in the first quarter, but it was too late compared to a long track record of red ink. Plus, it didn’t look sustainable: The full-year consensus forecast is less than $200 million.

Activists have been targeting E&P companies with high costs and weak governance with mixed results. Kimmeridge Energy Management Co. pushed for change at both Carrizo Oil & Gas Inc. and PDC Energy Inc., recently losing a proxy battle at the latter. Rising passive ownership via tracker funds and ETFs make it tough to unseat incumbent management; the scale of the collapse in EQT’s stock can only have helped in that regard.

Yet the fundamental problem in shale-land remains: Too many companies are chasing a finite set of prospects, with incentive structures that prioritize growth while frequently shielding management from the poor returns that follow. Until recently, generous funding from capital markets has enabled all this. The result has been a fantastic boom in U.S. oil and gas production that has also obliterated value in the industry.

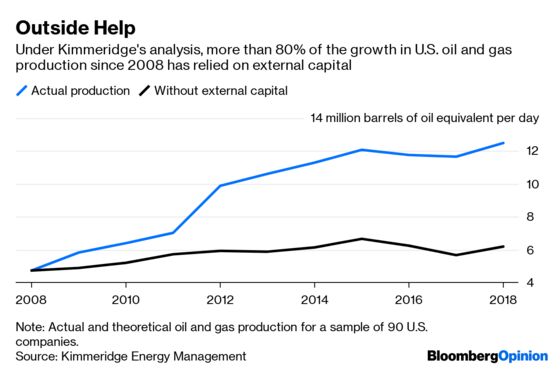

Kimmeridge has tried to quantify this. Analyzing almost 90 E&P companies, they looked at the recycle ratio, which compares profit per barrel with finding and development costs. Absent access to external capital, a producer needs a ratio of more than one in order to keep growing, and substantially more if they want to grow at the double-digit rates promised by many shale operators. Kimmeridge then compared actual production versus a theoretical production level as if the companies had lived within their means.

The results are striking. Under the more restrained case, production grows at a compound rate of 2.7% per year between 2008 and 2018. Actual growth: 10.2%.

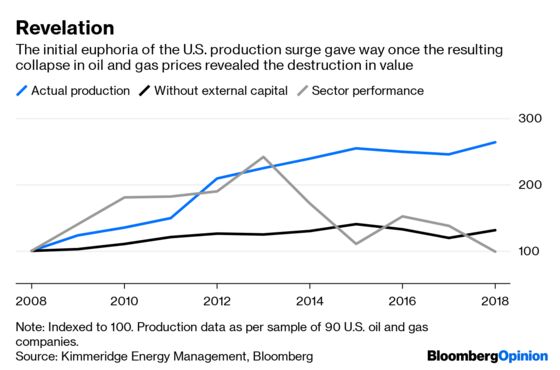

Cheap funding and an obsession with growth has done wonders for stuff like “energy dominance” and thrown OPEC for a loop. But it hasn’t done much for investors. Here’s a modified version of that chart, indexing it to the SPDR S&P Oil & Gas Exploration & Production ETF:

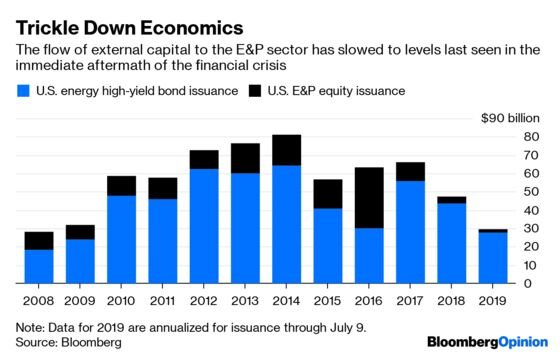

At this point, external capital appears to have dried up. On an annualized basis, high-yield energy bond issuance is running at its lowest level since 2009. Equity issuance, which surged in 2016 as E&P companies recapitalized amid the oil crash, has collapsed even more dramatically.

Barring a sudden outbreak of enthusiasm on the part of investors (perhaps on the back of an outbreak of war in the Middle East?), that spigot looks likely to remain closed. The longer it does, the harder it will be for many shale producers to promise both growth and a decent free-cash-flow yield. That has implications for robust U.S. production growth forecasts. Above all, though, it serves to reiterate the need for consolidation and streamlining in an industry that has over-capitalized and under-delivered.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Gongloff at mgongloff1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.