(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It will be the biggest initial public offering of a private equity firm for a decade. EQT AB’s prospective shareholders will need to believe the stock will fare better than those of its U.S. counterparts.

The big U.S. buyout firms went public in a rash of listings kicked off by Blackstone Group Inc. in 2007. Raising capital helped them to develop their businesses – but shareholder returns since have been mixed. Until this year, Blackstone and Carlyle Group LP had seen their stock underperform the S&P 500 index.

True, Switzerland’s Partners Group Holding AG has far outpaced its local benchmark since going public in 2006; but the overall impression is that private equity sits ill with public markets.

Enter EQT. The Swedish firm, founded by the Wallenberg family 25 years ago, confirmed Monday it will seek to raise at least 500 million euros ($548 million) in a Stockholm IPO. It said a year ago it wanted to raise capital. The question was how. EQT could surely have found the money privately. The industry likes chewing on itself: Blackstone last month agreed to buy a minority stake in BC Partners, a British leveraged buyout firm.

The advantage of an IPO is that the company’s existing owners get the chance to cash in their holdings over time. The Wallenbergs still own 23% of EQT. The remainder is held by 70 individuals, with around 45% owned by just ten people. Together, they will reap an undisclosed sum in the deal.

EQT’s economics aren’t dissimilar to those of conventional asset managers. Only 25-30% of future revenue will come from its slice of the gains on portfolio investments. Most income will be from recurring management fees. Earnings were 110 million euros in the first half. Annualize that and apply an 18 times multiple, somewhere between the U.S. firms and Partners, and the equity valuation would be around 4 billion euros before factoring new money raised in the IPO.

The partners have agreed not to sell further holdings for three to five years after listing “without consent”; there doesn't appear to be an immediate succession issue looming. That offers some comfort this isn’t a thinly veiled rush for the exit.

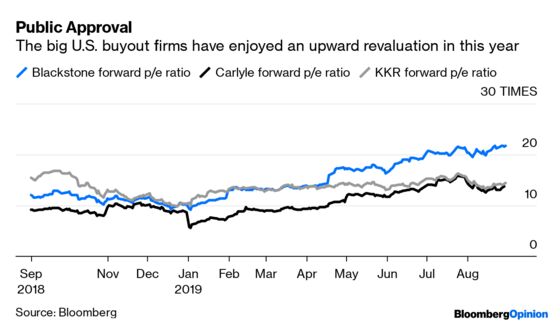

The share-price performance of the U.S. peers is partly down to their arcane governance, something that is being remedied. Blackstone and Carlyle said this year they were converting from partnerships to corporations. Valuations have climbed accordingly. The good news is that EQT has always been a corporation and will have a one-share, one-vote governance structure from the get-go.

Pension funds and wealthy investors are throwing money at private equity, so EQT’s market is growing. Having a proprietary pot of capital makes sense – it helps to seed new funds when clients are wary of innovation. The big unknown is the firm’s ability to secure the best investment opportunities. Right now, deal-makers are long on capital but short on targets. EQT’s Scandinavian connections set it apart. That should help it to grow in an industry that already has more money than it knows what to do with – but it’s no guarantee.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Edward Evans at eevans3@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Hughes is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals. He previously worked for Reuters Breakingviews, as well as the Financial Times and the Independent newspaper.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.