Ending a Road Trip With Abe, With Many Miles Left to Go

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- What holds America together?

I’ve asked scores of people that question over the past five months of driving a 25-foot Winnebago cross-country on local roads. My wife Laurel and I left Times Square on Sept. 11, taking the old Lincoln Highway — America’s first transcontinental road — to its terminus in San Francisco, before heading down the coast, turning east across the Southwest, through Louisiana to our destination: New Orleans.

The idea was to stay off the interstates and out of the headlines to ask people about their lives and their work, with the hope that — by hearing national issues described from local and personal perspectives, and by stepping away from the consuming frenzy of presidential politics — we might see the country’s challenges a little less rigidly, see our fellow citizens a little more empathetically, and think about the ideas and values that bind us.

To guide our journey, I leaned on the spirit of Abraham Lincoln, who in striving to reunite the country recognized that his opponents believed they, too, were in the right. Lincoln understood that reconciliation requires humility. The “charity for all” that he extended to secessionists, and challenged the public to support, had little do with Christian morality and everything to do with American patriotism. His faith in the importance of preserving the union was paramount — too much so, say some modern critics, who note that Lincoln was no abolitionist. Yet had he been, had he held our modern view of racial equality, he never would have been elected president. What then?

History is complicated. We simplify it to fit the stories we want to believe, sometimes having grown up with them, and we too easily reject views that call them into question. One of the reasons Americans have grown so intensely divided is that our national politics have become as much about our vision of the future as our understanding of the past.

In recent years, many Republican leaders have championed an idealized past — Make America Great Again — as Democratic activists have held its heroes to present-day standards, with each side vilifying the other’s view of history. Caught in the middle is the vast majority of Americans who get pulled into arguments they’d rather not have — in part because they have more pressing concerns in their own families and communities, but also because the debate surrounds an uncomfortable subject: race.

Since leaving California, I’ve been struck by what I have not seen: monuments to Lincoln. Across the North, we could hardly drive a day without seeing a Lincoln statue. In the South, there are almost none. When a Lincoln statue was dedicated at a National Park Service site in Richmond, Virginia, in 2003, protesters attempted to disrupt the ceremony. Driving through Texas, I recalled Senator Ted Cruz, last October, criticizing protesters in Oregon for tearing down a statue of Lincoln, and yet we saw no public statues of Lincoln in his home state.

Again and again, I’ve heard people say they wished our elected leaders in Washington were more practical, wanting them to put compromise over combat. But for politicians, most of the rewards — in media coverage, fundraising and votes — derive from combat. And today, the most fiercely contested ground is national identity: what we were, what we are, and what we should be.

As a result, arguments over Civil War monuments and other public legacies of slavery are extending to all aspects of our history. Earlier this week, the San Francisco board of education voted to remove the names of Lincoln, Washington and others from its schools.

These are important conversations, but media coverage amplifies the loudest voices, who almost always oversimplify and ignore unhelpful facts. Their goal is not reconciliation through understanding. It’s victory through divide and conquer, leaving each side to view the other as irredeemable. Lincoln’s spirit of charity — the respect he afforded opponents and their arguments, the humility with which he declared his own position, the logic and reasoning he applied to controversies, and the heartfelt appeals he made to our familial bonds — can be hard to find.

But so it has always been. Politics is a blood sport. Lincoln is worth remembering today as much for what he did as the spirit with which he did it, as exceedingly rare then as it is now. With the nation again torn in two, we can either call on that spirit in the name of unity, or reject it in the name of righteousness. Human nature defaults to the latter, our better angels call us to the former. The choice is each of ours to make.

Lincoln’s last speech, two days after Robert E. Lee’s surrender and three days before his assassination, concerned the burning question on everyone’s mind: how to bring the country back together. Lincoln offered conciliatory comments toward Southern states and focused on the controversy surrounding Louisiana’s new constitution, which northern Republicans in Congress opposed because it did not include Black suffrage. He spoke in favor of the state’s constitution on entirely pragmatic grounds, noting that it provided public schools for Blacks and Whites, and arguing it was better to accept it and improve it than to reject it and lose the state’s votes for the 13th Amendment banning slavery.

At the same time, Lincoln did something he had never done before: He publicly expressed his support for conferring voting rights on at least some Black men — “the very intelligent, and on those who serve our cause as soldiers.” John Wilkes Booth, after listening in the audience, declared, “That is the last speech he will ever make.”

We sanctify Lincoln for giving his life to the battle for union. But he was murdered after the war was over, at least in part because of his support for voting rights and Black political power — the same reason that, for a century to come, many Black Americans would be murdered and terrorized.

A few days before President Joe Biden’s inauguration, I meet Justin Nystrom, a professor of history at Loyola University, at the Roosevelt Hotel in New Orleans, the place where Huey Long once sipped gin fizzes. It is also the site where, 15 months after Lincoln’s last speech, hopes for peaceful reconciliation died, along with more than 30 Black men, massacred while attempting to attend a constitutional convention convened by Republicans to extend suffrage. Democrats, many of them Confederate veterans and led by the city’s mayor, opened fire and brutally attacked the Black marchers. In the bloody aftermath, many arrests were made — of Black citizens, by police officers who had carried out the attack. There is no monument to those killed, nor any public marker of the massacre.

There was more violence in the years that followed. In 1873, with Republicans back in charge but Democrats crying foul over voter fraud and a stolen election, Republicans attempted to seat a county judge, leading to the massacre of more than 100 Black men. The Supreme Court later ruled that the federal government could not prosecute the killers. The next year, a White League militia attacked the police and attempted to overthrow the government, leaving more than 30 dead. No arrests were made.

“If you don’t arrest people who do this,” says Justin, who wrote a book on Reconstruction in Louisiana, “they’ll be back, because they always come back when you don’t arrest them.” He sees the racism of anti-Reconstruction forces in the violent mob that stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6, Confederate flags and all, and he doesn’t see it going away. (Two weeks later, the Department of Homeland Security would issue a bulletin warning of an elevated threat from “ideologically motivated violent extremists with objections to the exercise of governmental authority and the presidential transition, as well as other perceived grievances fueled by false narratives.”)

Justin laments that the primary slogan for racial justice has ended up being divisive: “I always contend that [Black Lives Matter] should have requisitioned ‘law and order’” as a rallying cry, he says. “Because ultimately it’s about the 14th Amendment, and their theme should have been, ‘We want law and order,’ because that’s only fair — equal protection under the law is what they seek. And I thought stealing that, appropriating that from the right, would have been a twist, but nobody asked me.” Swords into ploughshares, dog whistles into peace pipes.

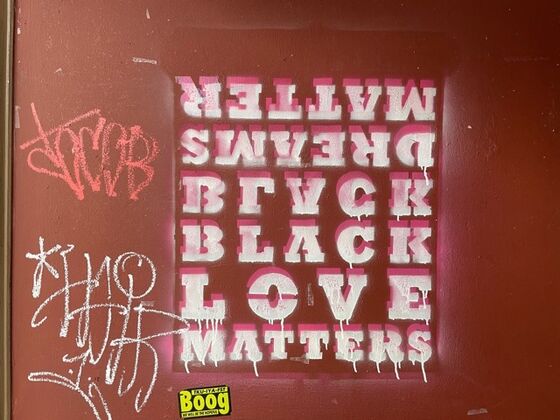

Instead, we have tribalistic flags — Black Lives Matter versus Blue Lives Matter — that have ended up pushing people into making a false choice: Stand with Black Americans or stand with police officers — one or the other, as though we can’t do both. All across the country, I saw countless BLM signs and countless thin blue line American flags. I never saw one house, one business or one RV displaying both. Most Americans do, quietly, stand with both groups. But in front yards and store fronts, we see only division, centered on that hardest and hottest of topics, race.

To some extent, those divisions are an inevitable part of the national reckoning over race that has only just begun. Justin mentions that his profession, long dominated by Whites who have downplayed racial injustice, has been part of the problem. “The Cold War has freed us up as historians to tell the truth about ourselves,” he says. “When you had the Cold War, you had to pump up American institutions as [being] what I call the conveyor belt of progress. But when the Cold War ended, we no longer had this kind of obvious enemy, and we still don’t.” Without a clear military enemy, we have had a lot of time to look in our national mirror.

“I think there’s a lot of questioning about the American mission,” he says, “and I think this reckoning that we’re doing with our history — whether it’s the monuments, whether it’s finally coming to grips with ‘Birth of a Nation’ — there’s a lot of the country that’s just not ready for that. Every country believes its own myths. That’s what kind of holds it together, right?”

Without me asking it, he’s answered the question I’ve put to every person I’ve met along my journey — What holds America together? — and he’s gotten right to the heart of it: “I don’t mean to be cynical about this, but when you quit believing, when a country no longer agrees on the story” — the bonds of union begin to slip. “And we’re a long way from agreement on the story of what the country means.”

Most people I’ve spoken with over the past five months, when I asked them what holds America together, talked about freedom and democracy, equality and the Constitution, opportunity and ambition, God and family. But the more I listened to them answer another question — What’s your biggest fear about the future of the country? — the more I came to hear something else: respect for opposing views and tolerance for differences.

Again and again, people mentioned their fear of the country dividing into partisan camps that don’t communicate civilly with each other, consume separate news, and generally think the other side is irredeemable. They frequently blamed social media for tearing apart families, friends and the country itself. It may be that the breakdown of the nuclear family has extended to the American family for a similar reason: If we don’t need to be in a marriage with people we can’t get along with, why stay? It’s easier to walk away. We see this retreat in communities’ increasingly homogenous political cultures. Self-sorting has come to feel normal and, worse, righteous.

As we retreat from one another, we lose trust. And that extends to our trust in the will of the majority and in the democratic institutions — the justice system, the education system, the media — that both underpin and check it. As trust erodes, so does faith in a shared national culture.

“I can't think of a lower point of what E Pluribus Unum” — our national motto, out of many, one — “might mean to Americans,” says Justin. It may be the bleakest statement I’ve heard the entire trip, but I’m not sure I can argue with it. “This is, to me, what’s different about right now [compared with] our entire history. Even the North and South in the Civil War sort of had this sort of similar conception. The North was, in many ways, just as White supremacist as the South…. We’ve done a good job, I think, over our history in coming back to that phrase. I’m hoping that in this hour where we seem so divided, that we can look at that old Latin saying and say, ‘Yes, that is who we are. And that is who we need to be.’”

I ask him what he fears most about the future of the country 10 years from now. “As the father of two sons, I most fear that they will have to fight for their country against their own countrymen. I think that’s a fear shared by many. Our children shouldn’t be fighting each other in the streets of this country to preserve it.”

It’s inauguration day in New Orleans, the end of a 144-day journey through America. After watching Biden invoke Lincoln in his inaugural address on Fox News — it was the only channel that came in on our television — I head out for lunch, picking up a bowl of crawfish etouffee at Mother’s Restaurant, established 1938, and walk over to Lafayette Square, passing a half-empty parking lot that was once heralded as the future location of a 69-story Trump-branded hotel. Across the street is a federal courthouse named for Hale Boggs, a local congressman who voted against the Civil Rights Bill of 1964 but supported the Voting Rights Act the following year.

A statue of Ben Franklin stands on the east side of Lafayette Square. On the west side, one of John McDonogh — a slaveholding real estate and shipping magnate who left his fortune to establish schools for Black and White children — is gone, toppled last July, leaving an empty pedestal. In the center of the park is a statue of Henry Clay, Lincoln’s hero, the Great Compromiser whose American System of political economy aimed to unify the country, and who held North and South together as the debate over slavery intensified.

Less well remembered is that, while Clay called slavery an evil and favored gradual emancipation, he himself enslaved 60 people. When one, Charlotte Dupuy, sued for her freedom, claiming it was promised by a previous owner, he was irate. She lost the case. Ten years later, he freed her and one of her two children, though not the other, nor her husband.

We rarely take note of the history all around us. It blends into the scenery. Of the millions who pass through Times Square each year, nearly all remember seeing Elmo or another street performer. Almost none notice the sign marking the Lincoln Highway. We name things for people because we know that, without conspicuous reminders, future generations will forget. But monuments have proven to be useful to us beyond what their benefactors and champions imagined.

By fixing our sights on the totality of their lives and legacies, we can begin to see ourselves more clearly. From the fullness of their shadow emerge harsh truths long obscured — on race and also on gender and sexuality, class and power — and hard questions about how to create a more equal society, a more perfect union. If we can discuss these truths and questions in the spirit of Lincoln, seeking to bind up wounds rather than settle scores, in language and sentiment that elevates national commonality without sacrificing political principle, with more listening and less snarking, there is yet hope for the last best hope of Earth.

As I walk through Lafayette Square, two Black men sit hunched over on the steps leading up to the statue of Clay standing tall, his eyes gazing to the heavens. They appear to be asleep, heads resting on arms, arms resting on knees, their faces hidden.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Frank Barry is a columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. This column is part of a series, “Looking for Lincoln: A Portrait of America at a Crossroads.” It features reports from Barry’s journey west along the Lincoln Highway, a zigzagging network of local roads running from Times Square to the Golden Gate Bridge, from Sept. 11 to Election Day.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.