(Bloomberg Opinion) -- I am practical, and probably boring, about cars. I have never owned one that makes people on street corners and outdoor cafes stare at me. But on a recent Sunday I was ogled in a vehicle that wasn’t particularly flashy or expensive. I think people were gawking because the car I was test-driving, an ElectraMeccanica Solo, is delightful, unusual and impossible to figure out with just a glance. So everybody stared — and smiled.

The Solo looks like something a sushi chef might concoct with a knife capable of slicing a full-sized car in half, precisely and with a bit of whimsy. It has one seat, two doors, three wheels and is technically considered a motorcycle. But it is fully enclosed in a lightweight, aerospace-composite chassis, has a comfortable cockpit, a digital instrument cluster, solid audio, air conditioning, heat, a camera for backing up, a little trunk and most other car stuff except extra seats and fellow passengers. You feel the road while driving it, and it handles and accelerates like a champ.

And the Solo is an electric vehicle. It can travel about 100 miles on a charge and has a sticker price of $18,500 — about $23,000 to $113,000 less than Tesla Inc.’s least and most expensive models. It’s truly an EV for the masses. It’s also an ambassador for a manufacturing boomlet in Arizona and elsewhere in the Southwest — which, in turn, offers other states a road map for attracting cutting-edge industries and promising startups.

While ElectraMeccanica Vehicles Corp., and its chief executive officer, Paul Rivera, vetted several states when the Canadian company was looking for a production home in the U.S., they ultimately settled on Arizona. Lighter taxes, looser regulations, a sophisticated economic ecosystem and a lower cost of living than neighboring states such as California informed that decision, but two other factors were pivotal. Arizona offered access to a talented labor pool, and the state went out of its way to help the company solve its problems — including coordinating a ride-sharing experiment central to its marketing plans.

“We get just one chance to do this. The vehicle has got to be right,” Rivera said. “The five municipalities around Phoenix stepped up and enabled us to test Solo-share. You know how hard it is to get municipalities to agree on anything?”

ElectraMeccanica recently broke ground on a state-of-the-art, 235,000-square-foot engineering facility in Mesa that will begin pumping out cars next year. It hopes to assemble 20,000 Solos and employ as many as 500 full-time workers there. The startup is in good company. Two technology behemoths, Intel Corp. and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp., are pursuing multibillion-dollar expansions in Arizona, other EV makers have launched there, legacy aerospace companies abound, major data centers and biomedical technology firms have arrived and Arizona continues to woo new enterprises.

Chastened by the Great Recession and the loss of 300,000 local jobs after 2008 in bread-and-butter businesses such as construction, real estate and tourism, Arizona changed its game plan. It used innovative private and public sector partnerships to help lure advanced manufacturers that also planned on exporting their products globally.

“It was a conscious decision by our business and political leaders to ensure we could diversify our economy so we could withstand future recessions,” said Sandra Watson, president of the Arizona Commerce Authority, the state’s leading economic development organization. “When we think about the future, we’re thinking about advanced technology.”

Watson has been courting businesses in Arizona for nearly three decades, and she said that the various teams she has worked with or overseen have attracted $45 billion in new investment and created tens of thousands of jobs. Echoing Rivera, she said talented workers are the first draw for companies relocating to the state or starting from scratch there.

Arizona, like the rest of the Southwest, faces some significant challenges. Drought, wildfires, soaring temperatures and other manifestations of climate change are ravaging the region and may change the calculus of companies pondering setting up shop there. Low-tax regimes are always attractive to corporations, but the cost of advanced infrastructure and higher-quality public education needed to fuel continued economic growth will test — and possibly strain — such public budget-cutting over time.

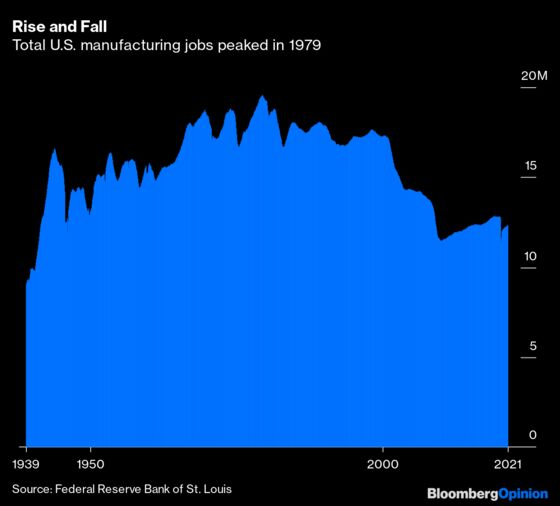

Although the U.S. remains a manufacturing powerhouse, a return to its brightest industrial years presents formidable hurdles. About 20% of the U.S. adult workforce — some 19.5 million people — held a manufacturing job in 1979, industrial labor’s peak year, according to Federal Reserve data. Employment in the sector has steadily plunged since then, to about 12.3 million people now, eviscerating what was once a reliable path to a middle-class life for blue-collar Americans. Offshore production, automation, trade policy, skill gaps and competitive weaknesses have all contributed to manufacturing’s decline.

For as heady as Arizona’s growth has been, the state has added only about 13,000 manufacturing jobs since 2015 — less than a dent in the broader context of overall job losses nationwide. While the state has about 180,000 industrial workers, that headcount lags well behind legacy manufacturing hotspots such as California, Illinois, Michigan, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Texas and Wisconsin.

Still, Arizona has spent years laying the groundwork for the gains it is enjoying now and exemplifies the payoffs that come with robust public and private planning. About 238 manufacturers relocated to the greater Phoenix area between 2009 and 2019, with more than a third of those arriving in 2018 and 2019 alone. A number of recent studies have shown that Arizona and some of its Southwestern neighbors are adding certain manufacturing jobs and increasing manufacturing production faster than other states. Companies also appear to be favoring the region, at the expense of legacy states, for new plants or for those repatriated from overseas— which may mean manufacturing’s future will be rooted there.

“Manufacturing” may evoke images of steel mills and heavy-duty machinery, but the top producers that economists and the federal government identify as manufacturers now occupy a different landscape. Chemical companies, computer and electronics makers, food, beverage and tobacco concerns and aerospace enterprises are the leading manufacturing categories in the U.S., followed by the auto sector, machinery makers, and metal, petroleum and coal producers.

The modern assembly line also is not your grandfather or your grandmother’s assembly line. Automated plants require far fewer workers, but those workers need greater training and more advanced education than their counterparts from the past. Smart factories that digitally integrate sensors, controls and software to enhance efficiencies and output at plants and adaptability along supply chains have also ratcheted up demand for skilled workers.

The Covid-19 pandemic — and its abrupt, brutal upending of business production and distribution worldwide — may mean that a reordering of global manufacturing relationships and supply chains is on the way. That possibly bodes well for domestic manufacturers at the top of their smart-manufacturing games. And smart factories and smart workers are what Arizona is targeting.

ElectraMeccanica, founded in 2015, fits that bill. Although it is publicly traded and the descendant of a sports car manufacturer that relocated from Turin, Italy, to Vancouver, it is very much a seedling. It lost $63 million on just $569,000 in revenue last year but had $260.4 million in cash on hand at the end of the first quarter.

The Solo’s kinks are still being ironed out, and its production run next year will be modest. But ElectraMeccanica thinks the Solo is a perfect fit for urban commuters, commercial fleets, the local delivery guy, drivers who like ride-shares, and teenagers prone to mischief when they have friends in their car. A majority of commuters drive alone to work anyhow, so the Solo got rid of all those unused seats.

Chongqing Zongshen Automobile Industry Co., a top motorcycle manufacturer in China, is helping ElectraMeccanica build the Solo and has a stake in the company. The car features a high-performance electric rear-drive motor that propels it to 60 miles per hour in about 10 seconds. Its speed tops out at 80 mph. (ElectraMeccanica is also developing a gorgeous upscale sports car, the eRoadster, for drivers who can’t bear being stuck at 80 mph; the two-seat EV will sell for about $150,000.) The Solo boasts a roll bar, side-impact protection, crumple zones and torque limiters but lacks air bags. (Motorcycles are not required to have them, and the Solo exploits that loophole.)

“This is our iPhone 1,” said Rivera, comparing the Solo’s rollout next year to the launch of a famous breakthrough product. “It’s a car that’s meant to help solve urban driving challenges and help address climate change. Those are our goals.”

Rivera said he began scouting manufacturing sites in the U.S. in late 2019 and enlisted BDO USA LLP, an accounting and consulting firm that specializes in such work, to advise him.

“The first thing to start with when you do this is labor. Everything else you’re looking at after that are costs, like taxes or shipping,” said Tom Stringer, who oversees BDO’s site-selection practice and worked with Rivera. “Labor gets you into skillsets, availability in the market, quality of life and inward migration patterns. It’s extraordinarily multifaceted on the labor side.”

“We’re seeing these decisions increasingly being shaped by personnel issues,” he added. “Where’s the talent?”

Stringer noted that many states — including Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee and the Carolinas — have sharpened their approach to wooing newfangled manufacturers. But he said that Arizona’s focus on semiconductors and electric vehicles has given the state an edge in those sectors and allowed it to create networks of suppliers, distributors and transportation hubs to support them. Arizona also has an advantage those other states don’t: Its proximity to California’s massive market.

He said ElectraMeccanica considered Arizona, the Carolinas, Colorado, Florida, Tennessee and Texas for its new plant before narrowing its choice to Tennessee or Arizona. Access to a pipeline of skilled workers and California tipped the decision to Arizona. Stringer also praised Watson’s attentiveness and understanding of ElectraMeccanica’s needs. He said he regards her as “the best state commerce secretary in the country by far — and I’ve worked with them all.”

Watson tips her hat to Governor Doug Ducey, noting that his administration prioritized recruiting manufacturers to the state years ago. She also emphasized that her team can tick off a number of important boxes for companies considering Arizona. That list includes lower corporate and personal taxes, a lighter regulatory touch, affordable communities, access to reliable supply chains and transportation and — always the closer — skilled labor.

“Innovators and business decision-makers look to Arizona because we have a complete package,” she said, noting that the state also plans to court companies specializing in financial technology, quantum computing and artificial intelligence.

For all of that, however, Arizona’s package has a significant hole in it if the state plans on remaining a competitive destination for manufacturers in the decades to come: Education.

Arizona has recently ramped up job training programs at its network of community colleges and its three public universities, leaning heavily on partnerships with local businesses to tailor curricula to meet their needs. Arizona State University offers meaty undergraduate and graduate programs in engineering and has had a longstanding academic and research partnership with Intel.

But the state also has a long history of underfunding education from preschool through college, especially compared with rival nearby states such as California and Colorado. Teacher shortages and crowded classrooms have been the norm in K-12 schools. Some state legislators have balked at spending more on colleges. And a state that traditionally tolerated high poverty rates and depended significantly on a poorly paid, low-skill workforce didn’t have much of an incentive to change course.

Now that Arizona is positioning itself as a destination for innovative manufacturers that rely on more highly skilled workers and engineers, how it funds education will matter even more than it did in the past.

Rivera said that business leaders in Arizona recognize that the state and the private sector need to make more serious commitments to education and are pressing forward on that issue. He also said that other looming problems, particularly drought and other impacts of climate change, are front-of-mind for the business community and are being taken just as seriously. Water conservation and recycling are standard operating procedure, he said.

In the meantime, Rivera has his shoulder to the wheel. He has a plant in Mesa to open and cars he wants to churn out.

“I couldn’t have picked a better location to build the Solo,” he said. “We’re excited to be here.”

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Timothy L. O'Brien is a senior columnist for Bloomberg Opinion.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.