Economy Has Plenty of Offramps Before Stagflation City

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- With the U.S. economy slowing and inflation rising, there are growing fears of stagflation, a combination of stagnant economic growth and high inflation. The example that comes immediately to mind for most people is the late 1970s and early 1980s, when inflation, interest rates and unemployment all surged to double digit rates, far outpacing real growth in gross domestic product.

The economy is nowhere near in as bad a shape today, but real growth and inflation are moving in the wrong directions. The Atlanta Fed’s nowcast of real GDP growth, net of inflation, estimates that the economy grew at an annual rate of just 1.2% in the third quarter, well below the economy’s long-term growth rate of 3.1% since 1947.

Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve’s preferred inflation gauge, the personal consumption expenditures index, rose 4.3% in August over the prior year, the biggest one-year jump since 1991 and more than double the Fed’s target of 2%. The consumer price index rose even higher in September, up 5.4% from a year ago.

It’s obviously not good that inflation is rising faster than real growth, as now appears to be the case. But it’s also not unusual, and it doesn’t necessarily mean the trend will continue. The economy has repeatedly shown an ability to correct course, and it’s a mistake to assume it won’t do so again.

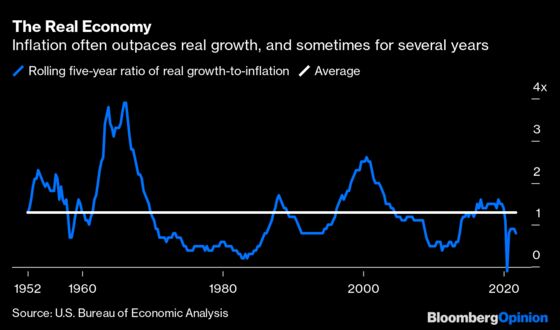

One way to follow the economy’s progress — and its frequent stumbles — is to track the ratio of real growth-to-inflation over time. It’s a useful measure because high inflation tends to be a drag on growth, so when real growth is rising faster than inflation, it’s usually a good sign that inflation is under control. Also, while persistently elevated inflation is bad, it’s less problematic if real growth is even higher.

It turns out that in the near term, inflation has exceeded real growth as often as the other way around. The growth-to-inflation ratio has dipped below 1 about half the time over rolling annual periods since 1947, counted quarterly. So it’s not at all uncommon for inflation to run hotter than real growth for a time.

Importantly, it doesn’t mean inflation will exceed real growth going forward. The historical correlation between the growth-to-inflation ratio from one quarter to the next is weak (0.32), and there’s no correlation from one year to the next (0.06). In other words, the economy could look entirely different in a few months. (A correlation of 1 implies that two variables move perfectly in the same direction, whereas a correlation of negative 1 implies that two variables move perfectly in the opposite direction.)

It’s not even unusual for inflation to outpace real growth for several years. The growth-to-inflation ratio has dipped below 1 roughly 40% of the time over rolling five-year periods since 1947, all clustered around five episodes. In three of them — the late 1950s, the early 1990s and the years after the 2008 financial crisis — the economy averted deeper stagflation. The one that began in the late 1960s devolved into hyperstagflation later in the 1970s, but it took many years and significant missteps in Fed policy to get there.

The fifth episode is the current one. Real growth dipped below inflation during the five years through June 2020, and the rolling five-year growth-to-inflation ratio has remained below 1 ever since. As the earlier occasions show, however, it’s not safe to assume that 1970s style stagflation is imminent or even likely.

What about that idyllic 3% real growth and 2% inflation, or some similar proportion of the two? It’s probably more an aspiration than reality. The growth-to-inflation ratio has registered 1.5 or higher just 30% of the time over rolling five-year periods, mainly during the 1950s and 1960s. Except for a brief period in the 1990s when dot-com mania momentarily juiced growth, the U.S. has chased that ideal ever since, mostly without luck. The ratio has averaged closer to 1.3 over the past seven decades.

In fact, there’s a good chance the economy will experience some degree of stagflation in the years ahead. The five-year breakeven inflation rate, or the difference in yield between plain vanilla and inflation-protected Treasuries, is as good a barometer as there is of future inflation, and it now stands at 2.7%. It isn’t easy for a mature economy like the U.S. to sustain real growth over that hurdle, so don’t be surprised if real growth lags inflation occasionally in the coming years.

That doesn’t mean current growth and inflation trends are acceptable, and the Fed will have to intervene if inflation moves higher or hangs around current levels, and perhaps sooner than later. But as the chatter around growth and inflation intensifies, remember that the U.S. economy is a moody, complex machine that rarely conforms to expectations, particularly when navigating disruptions like a global pandemic. Sometimes what it needs is a little time to get back on track.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.