(Bloomberg Opinion) -- For economists, the biggest problem with inequality is how little they really know about it. For the rest of us, the question should be whether knowing more makes sense as a priority.

A recent edition of The Economist contains two primers on how the popular inequality research of star economists such as Thomas Piketty and his frequent collaborators Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, showing that the rich are getting richer while the poor are getting poorer, has been challenged by other academics. Most recently, Gerald Auten of the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Tax Analysis and David Splinter of the U.S. Congress’s Joint Committee on Taxation took issue with how Piketty, Saez and Zucman used tax data to come to the conclusion that the wealthiest Americans’ share of national income has risen fast in recent decades while that of the bottom 50% has decreased. Auten and Splinter calculated that the income shares of both the richest and the poorest have barely changed since the 1960s.

There’s plenty of other literature, mentioned in the Auten-Splinter paper, the Economist articles and elsewhere, that challenges the methods used by Piketty and his collaborators. Such challenges are mainly possible because tax data draw an incomplete and often difficult-to-interpret picture of the income distribution. Tax systems are complex, different governments choose not to tax different kinds of income, and of course people, rich and poor, cheat on their tax returns. Measuring wealth inequality rises to a whole new level of difficulty: Since so few countries have wealth taxes these days, only guesstimates of the wealth distribution are possible.

So on Tuesday, Piketty, Saez, Zucman and a long list of other signatories issued a sweeping response to critics of the popular inequality narrative, pointing out that all the data-based arguments can be settled by making solid data available. The World Inequality Database, on which much of their research relies, is a compilation of information from official, semi-official and unofficial sources ranging from government statistics to journalistic estimates. That’s the only possible approach, the economists argue, when governments don’t provide enough properly organized data.

“It is critical that we develop an internationally recognized set of indicators and methods for tracking income and wealth,” Piketty and others wrote. “Government statistical agencies should be publishing the income and wealth levels of the top 1%, 0.1%, and 0.001%, as well as the effective taxes paid by these groups.”

For research purposes, of course, it would be great to have definitive official data on wealth and income inequality. If everyone could agree on a single standard for the underlying numbers, only the conclusions and policy recommendations would be open to debate. But, leaving aside the difficulty of achieving that across a multitude of countries with widely diverging tax systems and evasion levels, one has to wonder whether it makes sense to worry so much about the “top 1%, 0.1%, and 0.001%.”

In their rebuttal, Piketty and others argue that this “Dark Ages of inequality statistics” we live in carries risks for democracy, and is hard to accept in a world where global tech and credit-card giants know so much about each of us. They also point out that “whether or not inequality is acceptable — and whether or not something should be done about it — is a matter of collective choice.” Cleared of powerful emotions such as jealousy, that choice becomes one of setting goals. Is greater economic equality the ultimate goal in and of itself? Or is there a higher purpose, such as making people happier, perhaps?

If that’s the case, it’s worth looking at Finland’s recent trial of a universal basic income. It revealed that paying people such an unconditional income doesn’t help get the unemployed into work — but it does make them happier. It’s not really about reaching a greater statistical level of equality with the top 0.001%; that’s not a meaningful concept to most people. With the basic income replacing means-tested benefits, people merely feel less stress when they don’t have to prove that they require help from the rest of society.

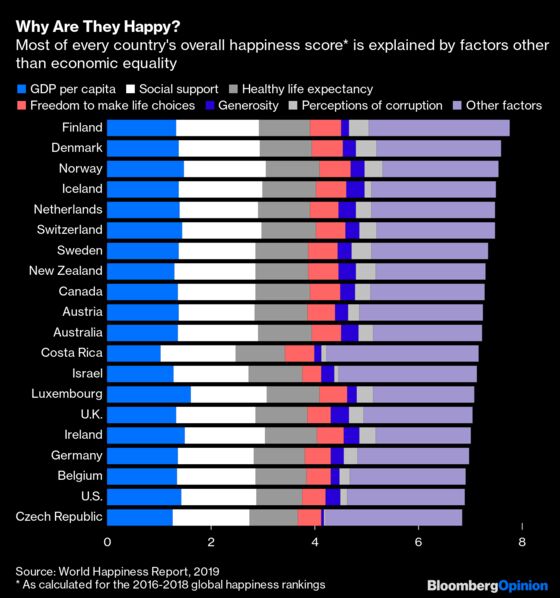

Happiness is too complex a phenomenon to be measured using income and wealth distributions alone. Inequality is one of the factors affecting a country’s place in the happiness rankings, but, for example, Costa Rica, ranked 12th in the 2019 World Happiness Report, has about twice the inequality level of the Czech Republic, which is ranked 20th. It’s not necessarily true that the Nordic countries are the world’s happiest just because they also rank high in income and wealth equality: Other factors account for the majority of nations’ happiness levels, such a country’s overall wealth, corruption perceptions or the robustness of the social safety net.

If happiness is the ultimate goal, tracking the income shares of the wealthiest isn’t necessarily worth the trouble. Working out a standard set of indicators that need to be improved to make people more satisfied with their lives would make more sense on a policy level. It’s a broader task than revising the United Nations’ System of National Accounts, an effort to which Piketty and other students of inequality are currently contributing. It’s fine for these experts to focus on inequality, if not necessarily on the top 1% of the income and wealth distribution; governments, by contrast, should be able to maintain a broader focus.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Melissa Pozsgay at mpozsgay@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.