Economic Nationalism Made Eastern Europe More Resilient

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Whether eastern European economies are dragged down by a likely German recession is a good way to test the idea that they are effectively colonies of their much larger neighbor, or “foreign-owned countries,” as some economists have dubbed them. So far, it looks as though the nationalist governments in Poland and Hungary have managed to reduce their dependence enough to build up resilience to spells of German economic weakness. Others should take steps in the same direction.

Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Poland and Romania all owe their spectacular recent economic growth at least in part to Germany. German companies have integrated these countries into their export-oriented production chains, helped drive down unemployment rates and set standards for labor conditions and quality. Collectively, these five countries’ trade turnover with Germany reached 325.3 billion euros ($360.8 billion) last year, 63% more business than Germany did with China. For all five economies, Germany is the biggest export market.

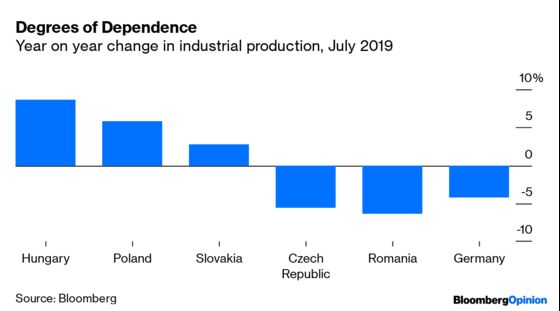

So when the German economy shrinks, as it did in the second quarter of this year and could do again in the third, this should send shock waves through eastern Europe. And indeed, growth has slowed a little throughout the region. But in some countries, these shocks are much more painful than in others, as the latest industrial production data show.

So far, Romania and the Czech Republic appear to be the most affected, while Hungary, Poland and Slovakia have resisted the downturn. What have they done differently?

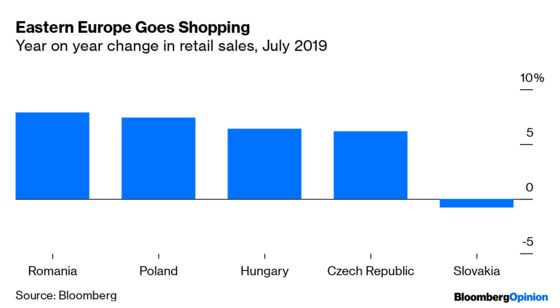

All five eastern European economies suffer from labor shortages after years of low birth rates and high emigration. The low unemployment rates are driving up wages and domestic demand. In four of the five countries – Slovakia is the only exception – retail sales are showing healthy growth.

Domestic demand, however, is the highest in three countries with the most expansionary fiscal policies: Romania, Hungary and Poland. In the latter two, nationalist governments have made big social promises, arguing that their countries’ living standards need to catch up faster to those of Western Europe, but they have the cushion of trade surpluses. Romania, by contrast, depends on imports and its shaky Social Democratic government only survives thanks to generous social spending.

Poland and Hungary, as well as the Czech Republic, have pursued conscious policies aimed at reducing their dependence on Germany. In 2000, 42% of the Czech Republic’s exports were going to Germany, but that share went down to 32% by 2018; Hungary and Poland have also reduced their export dependence on Germany by 10 percentage points and 7 percentage points respectively during the same period but they’ve done more than just weaning themselves off Europe’s biggest economy. Poland, for instance, now produces more finished products than intermediate goods such as parts, which wasn’t the case at the turn of the century.

It appears that the sweet spot of maximum resilience to German malaise lies at the crossroads of fiscal expansionism and a conscious strategy of export diversification. Eastern European governments that adhere to this policy mix often have been described as “populist” and their economic nationalism has been questioned. But even though their illiberal political practices have undermined basic freedoms, spawned corruption and sometimes subverted justice, their economic vision appears to be paying off – at least while labor markets hold and inflation remains manageable.

Romania joined the European Union later and started from a lower base than the others. It hasn’t had enough time to diversify exports or boost production of finished goods, so it’s more exposed to a downturn in Germany and in the euro area in general. Slovakia is equally at risk because of its outsize dependence on German automakers and its membership of the euro, which means it can’t control monetary stimulus like its neighbors with their own currencies can.

Germany isn’t a bad country to depend on: Its powerful export engine remains reliable even in the face of global trade wars. The trick for eastern Europe, which German investment has both enriched and, to some degree, subjugated, is to keep the dependence from becoming unhealthy – and to make sure living standards are increasing to offset any temporary economic trouble.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stephanie Baker at stebaker@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.