(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Eastern European countries are aggressively raising minimum wages in the face of acute labor shortages. Nevertheless, these economies are retaining their international competitiveness and still growing faster than their wealthier neighbors. The region’s nationalist and populist governments are succeeding with policies their liberal predecessors wouldn't have risked.

But the success won't last forever without more complex and targeted policies.

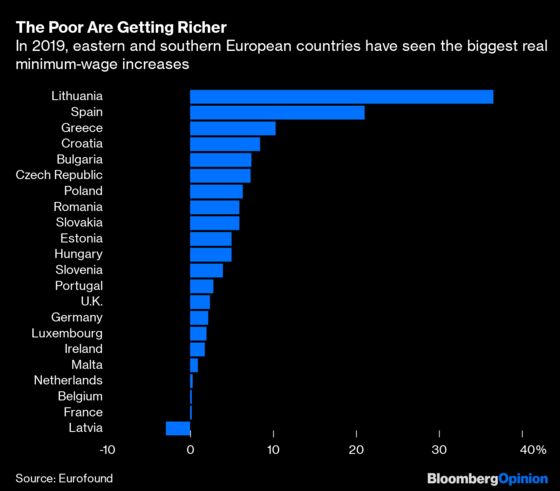

This year, real minimum wages have increased across Europe. Latvia is the only exception: The three-year agreement between employers, employees and the government that was signed in 2017 didn’t call for a minimum wage hike this year, so it declined in inflation-adjusted terms. The countries of southern and eastern Europe, where the minimum wages are the lowest, posted the highest increases

The trend is going to continue in 2020 and beyond. Poland is planning a 15.6% nominal minimum wage rise in 2020 and another 15.3% hike the following year. Slovakia is upping the statutory minimum wage by 11.5% next year, Lithuania by 9.4%, Hungary and Romania by 8%. It’s as if Eastern Europe has woken up from a nightmare in which it absolutely had to keep its wages low for fear of losing their German- and French-owned factories — and is trying to compensate for the fright it got.

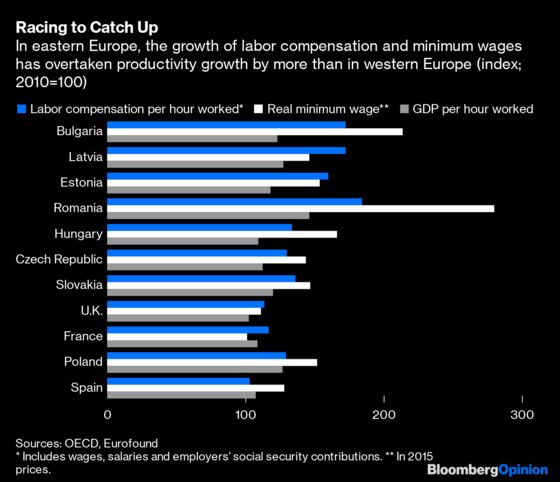

Some might even say they’re overcompensating. In much of the world, wage growth has decoupled from productivity increases in recent years, but in the east of Europe the disconnect has been bigger than in the continent’s west. Labor shortages caused by emigration and the significant foreign investment in industry have made sure wages have been going up at a much faster rate than productivity.

The trend has been there for a decade — and yet the eastern European economies have remained competitive. They are still the European Union’s fastest-growing ones, despite a general slowdown, and foreign investment has been robust.

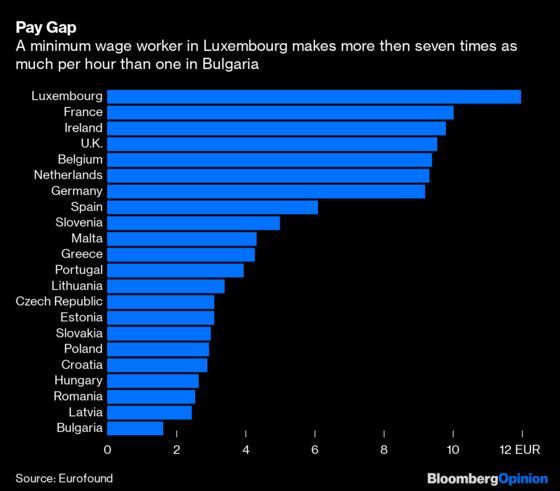

In 2009, Andreas Noelke and Arjan Vliegenthart wrote a seminal paper describing the post-Communist economies of Central and Eastern Europe as “dependent” ones, locked into providing cheap labor to mostly foreign-owned enterprises. Much has been said and written since about the limitations of this model. Indeed, within its confines growth is only possible while workers are poorer than in neighboring countries. This naturally leads to high inequality — only much of it is hidden from official statistics because a disproportionate share of income and wealth accrues not to the richest 1% of a country’s residents but to foreigners.

The sense of treading water economically has led to the rise of nationalist and populist governments in the region. They have promised to rectify the problem through higher taxes on the foreign owners, which would be redistributed through higher social transfers. Poland’s famous 500+ program, which distributes cash to families with children, is a prime example. In Hungary, Romania and elsewhere, populist governments have lured voters with generous handouts of this kind.

These social policies, whatever one might think of their efficiency, have pulled people out of abject poverty, reduced inequality and boosted domestic spending, which is now the major contributor to eastern European growth.

Raising minimum wages is another tool the populist governments are using to reach the same goals. Essentially, these governments have taken over the function of labor unions, which are weak in much of Eastern Europe. They are pressing for pay convergence with western Europe by using their ability to set the wage floor.

The Eastern European minimum wage policies have few immediate disadvantages. In a recent analysis of the Polish wage increase, a team economists from ING Groep NV wrote that the move created the twin risks of accelerating inflation and depressing investment. But, they added, “in the short term, this will be offset by higher consumption growth.” Following the news of the hike, ING revised its 2020 growth forecast for Poland by 0.1 percentage points to 3.4%.

But the problem with these policies, as with generous and broad social programs like 500+, is that they are blunt tools. They increase the poorest workers' welfare (if, that is, firms actually stick to the minimum wage requirements, which is not a given in Eastern Europe). But they don’t fix the structural problems with the region’s compensation practices, which have developed over the post-Communist era.

In a recent paper, Jan Drahokoupil and Agnieszka Piasna of the European Trade Union Institute in Brussels wrote that wages in Eastern Europe aren't just relatively low in manufacturing, in keeping with the “dependent economies” concept. Returns to higher skills and education are also generally lower than in the west. That goes, for example, for public service and education — two areas that aren’t “colonized” by foreign companies. In fact, the gaps are even bigger there. According to Drahokoupil and Piasna, the average education worker in Poland, Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic makes about 1,017 euros ($1,131) less per month than a German peer, while in manufacturing, the gap is smaller, at 833 euros.

Fixing such disparities requires more complex policies than social handouts and minimum wage rises. Governments need to seek ways to bring returns to training to the level of wealthier nations. Then, policies aimed at reducing poverty will no longer pose risks for Eastern European countries’ international competitiveness. In theory, governments that win one election after another on the back of their social generosity should be able to move on to more difficult tasks as they gain more experience. Otherwise, the current policies will lose their potency, and the populist leaders aren’t going do any better than their liberal predecessors.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Tobin Harshaw at tharshaw@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.