Deadly Viruses Aren't Pharma's Top Priority. Why Not?

There are significant disincentives for big drugmakers to go big in medicines to fight infectious diseases. This needs to change.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Drugmakers have made significant scientific advances in recent years. Unfortunately, their ability to combat potential pandemics isn't included.

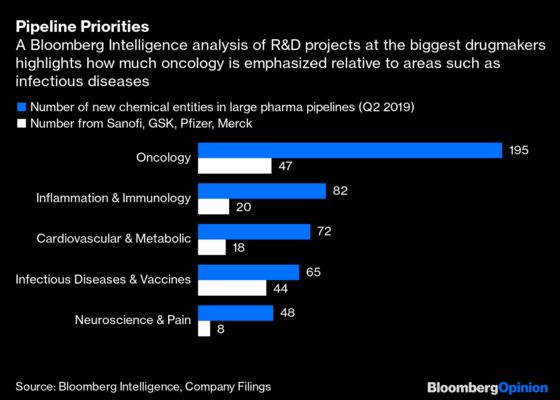

Driven in part by high prices and an easier path to profit, pharmaceutical companies have increasingly focused on medicines targeting cancer and rare diseases, and they are often amply rewarded by investors for doing so. That's helped lead to important new drugs and a notable drop in American cancer deaths. But, as I have noted, those efforts can come at the expense of vital but less lucrative work in the service of public health.

The recent outbreak of a deadly respiratory illness in China has reminded the world of the threat of new diseases and their potential for spreading globally. As part of efforts to contain the virus, China this week halted travel out of Wuhan and neighboring municipalities, while the World Health Organization said it will decide Thursday on whether to declare the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern as the death toll climbed. The current crisis may abate, but the threat of pandemics won’t. It's past time to take steps to make sure that the world has the scientific and medical firepower it will need — and large drugmakers could play a much bigger part than they are now.

Just 20 pharmaceutical companies spent more than $2 billion on research and development over the past 12 months, and they control the majority of the money spent on formulating new medicines. After years of consolidation, only four have major vaccine units. Smaller biotechnology firms are entering this area and could bring exciting new approaches to bear, but they are less proven.

While a virus is behind the latest outbreak, drug-resistant bacteria may be an even scarier long-term threat. Novartis AG and Sanofi, among others, have stepped back from the development of new antibacterials. There’s not enough new research, and as big companies disengage, antibiotic infrastructure could get weaker. That may lead to access and availability issues for even today's aging options.

If a company did develop a new class of antibiotics, doctors would use them as little as possible to avoid creating resistance. And vaccines for diseases that pop up sporadically aren't sure bets even to recover development costs. So there are significant disincentives for going big in these medicines as opposed to other more lucrative areas.

Publicly funded research can fill some gaps, but can't do it all. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention spent about $500 million on programs aimed at emerging infectious diseases last year, but is battling funding cuts. The National Institutes for Health sent about $5.5 billion to the institute that focuses on infectious diseases in 2019. Those funds also have to cover research into allergic, immunologic, and inflammatory conditions; only a portion goes directly to research targeting potential future pandemics, and it’s split between many labs and projects.

Public research also rarely turns into actual medicine without a pharmaceutical company's expertise. Merck & Co.’s Ebola vaccine, one of just a few recent success stories, originated in a publicly funded Canadian lab. The vaccine had looked promising for more than a decade, but it took years and multiple outbreaks for it to get developed and approved last year. The vaccine is a success, but not exactly a ringing endorsement for an ecosystem where fewer drugmakers have the ability or will to do this essential work.

The possibility for blockbuster sales motivates large drugmakers; little else moves the needle. The revenue potential for many infectious disease drugs is likely to remain limited, so other serious incentives are required. Whether it’s cash prizes that actually matter to companies that generate billions in revenue, or significant tax breaks, or extra market exclusivity for bestselling medicines, whatever it takes to get companies to re-engage is worth trying out. Just financing individual projects isn't enough; drugmakers need to feel reassured enough to rebuild the ability to develop and produce these sorts of medicines at scale.

At the same time, public efforts need more funding in order to make the basic breakthroughs that drugmakers can capitalize on. Researchers need an easier path to alliances with public health organizations and private companies that will see their best efforts make it to the market in a timely fashion.

Cancer and heart disease kill more Americans than infectious diseases in an average year. It could take take just one epidemic to change that, and we need to build a system that’s up to the challenge.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Max Nisen is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering biotech, pharma and health care. He previously wrote about management and corporate strategy for Quartz and Business Insider.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.