Did Novak Djokovic Really Pose a Health Risk in Australia?

The idea that Djokovic's refusal to be vaccinated could “excite anti-vaxxers” doesn’t seem serious, writes Therese Raphael

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Novak Djokovic knows how to pull off wins from tight positions. He has often been known to take a lengthy bathroom break before storming to victory. Not this time.

On Sunday, a federal court in Australia upheld the government’s decision to revoke Djokovic’s visa, ending a 10-day saga that saw him enter the country on a medical exemption from vaccination rules granted by the local state government, then be detained for violating federal visa rules and then released after a court ruled that border guards had not followed proper procedure.

But while he lost his bid to win a historic tenth Australian Open (which would have pretty much sealed his claim to be the GOAT in his sport), it’s not clear what the Australian government has gained here. In fact, it may well have made things harder.

Immigration minister Alex Hawke revoked Djokovic’s visa Friday “on health and good order grounds” saying it was in the public interest to do so. “The Morrison government is firmly committed to protecting Australia’s borders, particularly in relation to the Covid-19 pandemic,” he said.

Obviously, the unvaccinated Serbian made himself an easy target for a government looking for an election year victory. He double-faulted before even stepping foot in the country by failing to report recent travel to Spain on his Australian visa application and holding publicity events after having tested positive for Covid-19.

Djokovic has long been the marmite of tennis players. Tennis fans either love him (the clinical game, the movement) or loathe him (the bathroom breaks, the showy post-match gestures). He’s now a lot more controversial without playing a match down under.

But it’s worth asking what deporting Djokovic accomplishes. The idea that his refusal to be vaccinated could “excite anti-vaxxers” wasn’t serious. Djokovic’s opposition to vaccines was a matter of public record so he is already a poster boy for those similarly opposed. And most in that camp don’t need the validation. Plus, the player was sure to get a cool, if not hostile, response from a once-enthusiastic Australian audience who, as Prime Minister Scott Morrison noted, had sacrificed mightily to comply with lockdown rules.

More importantly, what actual health risk did Djokovic pose? Assuming he did indeed test positive on Dec. 16, or around then, his antibody levels would presumably be comparable to someone who has been vaccinated. Australians can usually get a temporary exemption of up to six months for a PCR-confirmed infection. He can be expected to follow other precautions, such as masking, during his stay. He already had a period of quarantine.

In the court of public opinion, which the government had a close eye on, Djokovic was doomed. A November study on attitudes toward vaccine mandates showed strong support for serious consequences for the non-vaccinated — and for exemptions to be tightly regulated for medical reasons, not for flimsy personal belief reasons.

In suggesting that Djokovic poses some level of threat to health and order, however, the government risks stoking the very fears it needs to tamp down if it is to wean people off rules that no longer make sense and transition to a different set of policies.

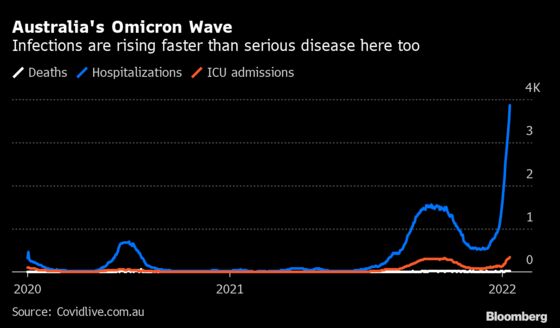

Such stringent border controls serve little purpose once transmission is well-established. Infection rates in Australia have climbed to the highest point since the pandemic began, with the seven-day average now more than 108,000 and the total number of confirmed Covid-19 cases reaching more than 1.6 million on Saturday. Hospitals in the worst-hit states, already dealing with staff burnout, face the crunch from rising admissions and staff shortages due to illness and isolation requirements.

Studies have shown that lengthy quarantines at this stage of the pandemic impose a heavy socioeconomic cost for no discernible health benefit. New South Wales health authorities have said that more than 90% of the cases there are the milder omicron variant, while more than half of those in intensive care in the state are unvaccinated (vaccination rates there are 94% for those aged 16 and over).

Part of the alarm about rising cases in Australia has been a shortage of antigen tests. The Djokovic drama has provided a convenient distraction from the government’s liability there. But sometimes a player wins a match despite a flawed game. Maybe the opponent shows up poorly prepared, or an unorthodox tactic catches him off-guard. Both seem to be the case here.

Australia’s government will have scored some points by deporting Djokovic, whose approach to vaccines and visa forms rightly offends many there. But in riding the wave of public indignation, the government has undermined its own case for a change in pandemic strategy and failed to rectify the problems in its own game.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Therese Raphael is a columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. She was editorial page editor of the Wall Street Journal Europe.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.