1.5 Million Unemployed Health-Care Workers Signal a Failed System

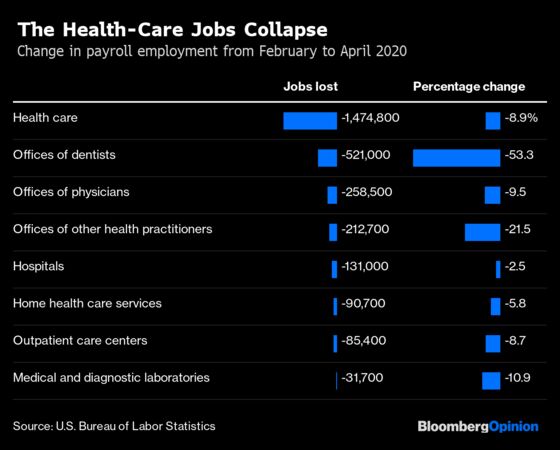

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Of all the industries to have shed lots of jobs since Covid-19 reached our shores, perhaps the most surprising to casual observers like me has been health care. We’re in the middle of a pandemic, and 1.5 million U.S. health-care workers have been laid off or furloughed since February.

Some of the job losses become more understandable as one looks through the above list. Of course dentists’ offices have had to be shuttered — the work of dentists and dental hygienists probably exposes them to more coronavirus risk than that of just about any other profession. And sure, going to the chiropractor or optometrist or podiatrist (among the “other health practitioners” in the table) isn’t really going to be a top priority in the early weeks of a pandemic. But hospitals have been shedding employees too, as have physicians’ offices, including a lot of primary-care practices. My primary-care doctor in Manhattan has been busier than ever, treating Covid-19 patients over the phone and sometimes in person (catching and recovering from the disease along the way), but has still seen a collapse in revenue and had to lay off staff.

It’s not that there’s a sudden shortage of cash to pay for care. The two main payers of medical bills in the U.S. are the federal government, which can effectively print money, and private insurers that are doing just fine at the moment. This structure has in the past made the sector largely recession-proof — even as nonfarm payroll employment fell by 8.7 million from January 2008 to February 2010, health care added 551,500 jobs.

The problem in a pandemic is the billing system. As a rule, health-care practitioners are paid not for taking care of their patients’ health but for performing specific procedures and other activities listed in the American Medical Association’s Current Procedural Terminology codebooks and databases. There are CPT codes for talking to a patient over the phone, but they’re usually reimbursed by insurers at lower rates than those for doing so in person. That can work out fine for dedicated telemedicine providers who don’t need medical equipment or office space in expensive neighborhoods, but for primary-care doctors it’s at best a stopgap. “Telemedicine for us is like takeout for restaurants,” said my doctor, Bertie Bregman. “It’s not going to pay all the bills, but maybe it will help keep us afloat for a while.”

Which brings me, somewhat belatedly, to the point of this column. At ChenMed, a Florida-based chain of primary-care practices that serve low-income senior citizens in 10 states, the decision was made in February to shift immediately from 98% to 99% in-office visits to 95% telemedicine. Well, “telemedicine” doesn’t quite describe it. “Our seniors can’t be running around, so we’re going to bring them food, toilet paper, medication,” ChenMed chief executive officer Christopher Chen told me last week. “If they’re lonely, we set up ‘love calls.’”

There are no CPT codes for toilet-paper runs or love calls, but that’s OK because ChenMed doesn’t get paid that way. Instead, it receives lump-sum payments from private insurance plans in the Medicare Advantage program. “We are something called global full risk,” Chen said. “Plans take out their administrative costs and a healthy margin, and give us the rest of the premium for us to pay for all of the costs: hospitals, doctors, drugs, etc.” ChenMed thus profits by keeping its patients alive and out of the hospital, not by running tests on them or operating on them or prescribing them drugs.

This method of paying for health care is not new. Mark Twain once recalled that his parents paid a doctor $25 a year in the 1840s (about $875 in today’s dollars) to take care of the whole family. The forerunners of Blue Cross and Blue Shield were organized along similar lines, as was the Permanente Health Plan established for Kaiser Shipyards workers in Richmond, California, during World War II. Although Kaiser Permanente has survived and grown by more or less staying the course, operating its own hospitals and paying the doctors in its network annual salaries, the Blue Cross and Blue Shield plans that came to dominate private health insurance in the post-World War II decades gravitated instead to paying hospitals and doctors for each service rendered. After Congress created Medicare and Medicaid in 1965, they followed the same approach.

A lot that ails the U.S. health-care system, the most expensive but far from most effective in the developed world, can probably be traced back to that decision. “The original sin of the current payment model is it’s fee for service,” said Rushika Fernandopulle, CEO of Iora Health, a Boston-based chain of primary-care practices that is similar to ChenMed (and is also in 10 states) but contracts with some employers as well as Medicare Advantage plans. “You do a thing to people and you submit a code and you get paid for that code. So you do more things.”

Iora Health and ChenMed figure prominently in two new books about improving health care in the U.S., “The Price We Pay,” by Marty Makary, a surgeon at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore and professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and “The Long Fix” by Vivian Lee, a radiologist and former hospital CEO who is president of health platforms at Alphabet Inc. subsidiary Verily Life Sciences. It was in a recent conversation with Lee that I learned both companies were humming along just fine amid the health-care retrenchment brought on by Covid-19. “They’ve had income,” she told me. “They haven’t had to furlough anybody.”

Efforts to shift the U.S. model away from paying for procedures and toward paying for results date back at least to the early 1970s, when the Nixon administration embraced health maintenance organizations to some extent modeled on Kaiser Permanente. HMOs did rise to prominence and in some areas dominance, but most were middle men that continued to pay doctors and hospitals on a fee-for-service basis. Still, they allowed room for experiments, like the one Christopher Chen’s parents, James and Mary, undertook in the 1990s by cutting deals with insurers to serve high-risk elderly patients in a poor section of Miami on a prepaid basis.

Medicare reforms enacted in 2003 made such arrangements a lot more attractive to doctors, and the Affordable Care Act of 2010 (aka Obamacare) committed the federal government to encouraging them across the board, policies that the current administration has continued to emphasize despite its overall hostility to the ACA. In response ChenMed, Iora Health and similar organizations such as Chicago-based Oak Street Health and California-based CareMore Health have been expanding rapidly.

Add all their patients together, though, and Fernandopulle estimates that they come to well under 1% of the U.S. population. And though established medical practices and hospital networks have also been experimenting with new ways of paying for care, egged on by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, doing that in conjunction with fee-for-service can be a difficult balancing act. “It’s been framed as having one foot on the canoe and one on the dock,” Fernandopulle said.

Could the terrible experience of fee-for-service medicine during the Covid-19 pandemic accelerate the shift away from it? As Fernandopulle put it: “The dock is burning, so maybe it’s time for everyone to jump in the canoe.” Or maybe it isn’t time — a few minutes later he mused that pandemic-induced financial troubles will force more independent medical practices to sell out to hospital networks or private-equity-backed chains, both of which would be likely to push them to maximize fee-for-service revenue. That’s what Chen sees as the likelier short-term outcome. “We have an entire system built around celebrating transactions and volume,” he said. “When that system begins to consolidate, everybody else is pushed even more in that direction.”

Fee-for-service is the establishment in U.S. health care, and establishments are hard to displace. “If you have decades of fee-for-service, think about the power structure, who brings in the revenue,” said Lee. “It becomes this self-fulfilling system.” It’s also a system that just broke down during a health-care emergency. Do we really want to revive it?

Yeah, same Bloomberg.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.