What Decades of (Sometimes Dodgy) Dietary Advice Made Us Do

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In September, a team of researchers made a well-publicized recommendation that people start eating... about as much red meat as they already eat. This was not based on any new medical findings, and was described by its authors as a “weak recommendation” with “low-certainty evidence.” But that was kind of their point. Previous warnings against eating red meat, they concluded, were “primarily based on observational studies that are at high risk for confounding and thus are limited in establishing causal inferences.” That is, we all eat and do lots of different things, and it’s really hard to suss out what causes what.

This new advice is part of a broader backlash against how nutritional research is conducted and communicated.

“The field needs radical reform,” Stanford Medical School Professor John P.A. Ioannidis wrote in the Journal of the American Medical Association last year:

Resources for some of these studies could have been better spent on unambiguous, directly manageable threats to health such as smoking, lack of exercise, air pollution, or climate change. Moreover, the perpetuated nutritional epidemiologic model probably also harms public health nutrition. Unfounded beliefs that justify eating more food, provided “quality food” is consumed, confuse the public and detract from the agenda of preventing and treating obesity.

This raises an interesting question. Have all these studies, and the official nutritional guidance that has sometimes flowed from them, really affected what people eat? If we’re about to embark on a wholesale reexamining of nutritional advice, it seems like that would be a good thing to know.

Happily, the U.S. Department of Agriculture keeps estimates back to 1909 of the per-capita “availability” of various foodstuffs. This includes food that is never actually eaten, and there are critics who say the early-1900s numbers aren’t to be trusted, but on the whole availability is considered a pretty good proxy for consumption. These numbers’ movements over time don’t exactly prove anything — that is, they “are at high risk for confounding and thus are limited in establishing causal inferences.” But I’m not a medical researcher, I’m a columnist who likes to make charts, which in this case help tell some interesting and important stories. Not necessarily simple ones, though:

The advice against eating red meat all started with heart attacks. In the U.S., heart disease went from relatively unknown in the late 19th century to the No. 1 cause of death by far, especially among men, in the 1950s and 1960s. Several different studies conducted just after World War II found big declines in heart disease deaths in European countries during the war, and attributed them to reduced consumption meat and other animal products. The “diet-heart hypothesis” was born and was, according to the University of Minnesota School of Public Health’s invaluable “History of Cardiovascular Disease Epidemiology” website, soon backed up by experimental and observational studies that pointed to fat in particular as the problem.

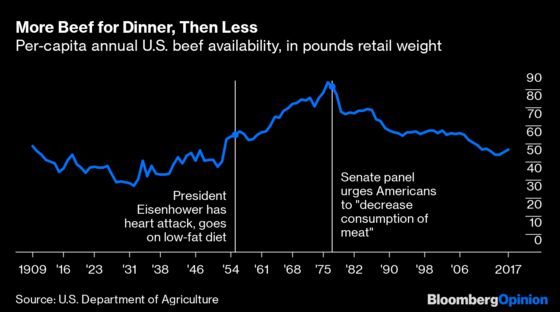

By the mid-1950s these results were beginning to be reported in the media. Playing a big role in this coverage was President Dwight Eisenhower’s 1955 heart attack and the low-fat diet his doctor subsequently recommended. In 1957 an American Heart Association panel issued a tentative warning on fat consumption, and in 1961 Time magazine put the leading proponent of the diet-heart hypothesis, physiologist Ancel Keys, on its cover. Keys kept delivering evidence after that, leading a “Seven Countries Study” that reported lower incidence of heart disease in Japan, where fat consumption was low, and in Southern European regions where it consisted mostly of olive oil, not animal fats.

Through all of this, as is apparent from the above chart, consumption of beef in the U.S. just kept rising. Then, in 1977, it began an abrupt fall. One noteworthy 1977 event was that a U.S. Senate select committee headed by former Democratic presidential nominee George McGovern advised Americans to “decrease consumption of meat.” So maybe people were just waiting for word from George McGovern.

Or maybe rising affluence proved stronger than the health warnings, until it didn’t any more. Growth in real, per-capita GDP averaged 3.2% a year in the U.S. from 1960 to 1973 (about twice as fast as in our current economic expansion), and the percentage of individuals below the poverty line fell from 22.2% to 11.1% (0.7 percentage points less than the current level). Eating beef was what prosperous people did, so more Americans ate more beef, and cattle ranchers geared up for continuing gains.

During the oil crisis and recession of 1973 and 1974, it became apparent that this had been a miscalculation. Demand softened, prices fell and the cattle industry lost $30 billion. Ranchers cut back their herds and let prices rise.

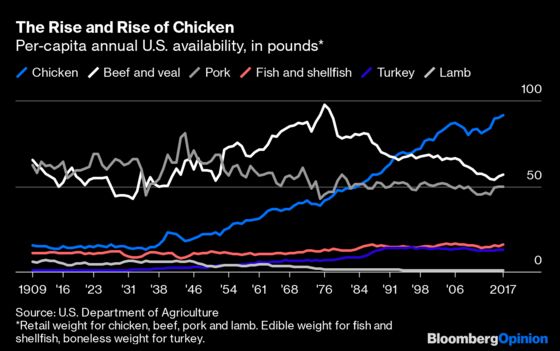

Meanwhile, a productivity revolution in chicken farming meant that there was a ready replacement waiting in the wings, with lower fat content and lower prices than beef. It had begun in 1923, when Cecile Steele of Ocean View, Delaware, ordered 50 chicks to replenish her flock of egg layers and was sent 500 by mistake. Steele decided to raise them for meat and sell them as soon as they were big enough, and her husband, Wilmer, built a small chicken house for them. “Her little business was so profitable that, by 1926, Mrs. Steele was able to build a broiler house with a capacity of 10,000 birds,” according to the National Chicken Council. By 1952 mass-produced “broilers” had replaced egg-laying farm chickens as America’s main source of chicken meat.

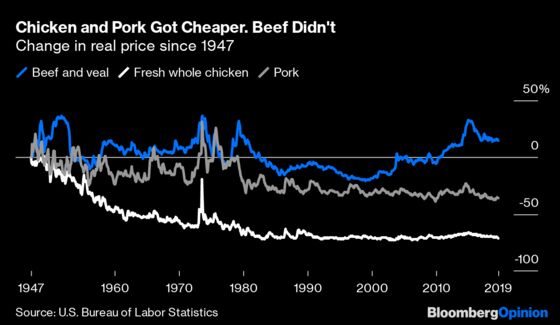

The ever-more industrial scale of the industry meant that this meat just kept getting cheaper and cheaper. Pork farming followed in chicken’s wake starting in the 1970s, and is now mostly an industrial, indoor endeavor as well. Beef cattle, however, still live most of their lives on the range before being brought to feedlots and fattened up. The cost of beef hasn’t fallen in real terms, and has gone up substantially relative to that of chicken and pork.

Beef lost market share after the mid-1970s to chicken, turkey and seafood. In relative terms it even lost ground to its fellow red meat pork. The pork industry did try really hard to run away from its association with red meat and fat, with a long-running “The Other White Meat” ad campaign and a successful effort to breed much of the fat (and much of the flavor) out of America’s hogs, but falling prices surely helped too.

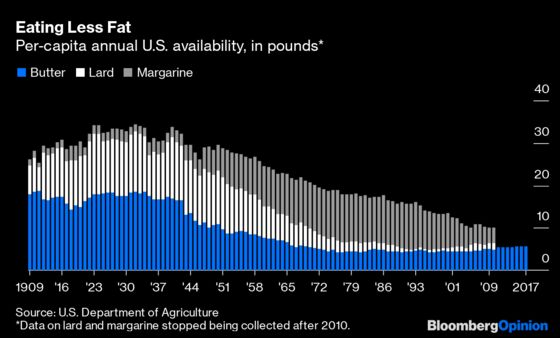

So the evidence on meat consumption is a little complicated, with factors other than dietary recommendations clearly playing a big role. Let’s take a look at some more direct sources of dietary fat: butter, lard and margarine.

Here the trend does mostly coincide with the anti-fat research findings, although it also seems to predate them just a little. The USDA only has data on vegetable oil from 1977 through 2010, but it shows a more than quadrupling of per-capita availability over that period, which makes one suspect that recommendations to eat like Southern Europeans really did have an impact. There was also a big displacement of butter and lard by (usually cheaper) margarine in the 1940s through 1970s. That has been partially reversed after research in the 1980s and 1990s showed that trans fats, which in those days were found in most margarines, were if anything more dangerous than animal fats.

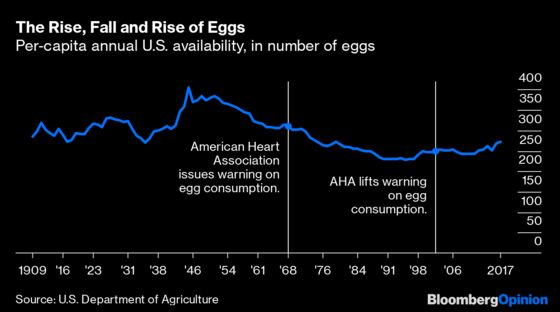

Eggs are another interesting case, in that they don’t contain a huge amount of fat but do contain cholesterol, the very substance that clogs arteries and can lead to heart disease. By the mid-1960s, researchers were positing a connection between egg cholesterol and bloodstream cholesterol, and in 1968 the American Heart Association issued a warning to limit egg consumption. By the late 1990s that theory seemed to have mostly fallen apart — although a study published just this March found that “each additional half an egg consumed per day was significantly associated with higher risk” of heart disease.

Again, it seems like the dietary recommendations have had an impact, but it’s also apparent that the decline in egg eating long predated the warnings. Perhaps Tony the Tiger is to blame. The Kellogg’s spokesfeline debuted in 1952, part of an advertising barrage by manufacturers of cereal and other breakfast foods that the egg industry didn’t counter with its own “Incredible, Edible Egg” campaign until 1976. It took a 1974 act of Congress allowing for a levy on egg production to fund research and promotion to get the American Egg Board and its advertising efforts going.

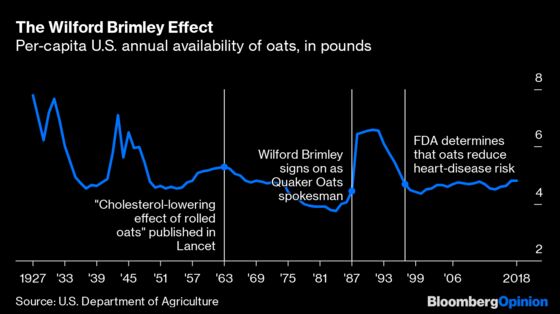

Another cholesterol-related advertising campaign of note was Wilford Brimley’s work for Quaker Oats, which began in 1987 and continued into the 1990s. The British medical journal The Lancet had published a study on the “Cholesterol-lowering effect of rolled oats” in 1963, which didn’t seem to have much impact, but then a flurry of studies in the early 1980s reported similar effects, a couple of best-selling books proclaimed the benefits of oat bran in particular, and Brimley’s “It’s the right thing to do” ad campaign expertly capitalized on the findings.

A single 1990 study concluding that oat bran “has little cholesterol-lowering effect” seems to have put a big damper on the oatthusiasm. Even though subsequent research has reaffirmed the oats-cholesterol link, and in 1997 the Food and Drug Administration began allowing Quaker to include claims about oats’ health benefits on its packaging, consumption hasn’t rebounded to anywhere near late 1980s levels. Why not? Well, breakfast cereals in general are now out of favor because they’re made out of carbohydrates and often contain lots of added sugar. A simple message — oats are good for you — has been muddled (although it does look like the spectacular rise of oat milk may be pushing oat consumption up again).

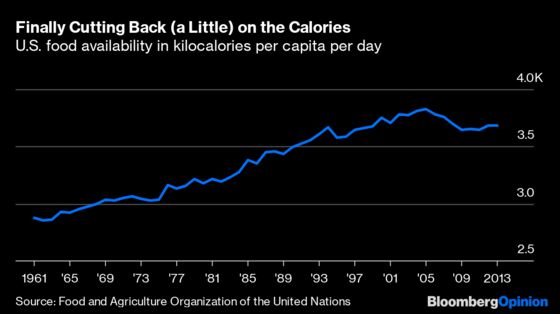

Clarity of message does seem to matter a lot. From the beginning of the diet-heart research in the 1940s, the benefits of simply consuming fewer calories were apparent. The American Heart Association recommendations of the 1950s and 1960s, the 1977 McGovern report and the official U.S. dietary guidelines that followed in its wake all emphasized the importance of keeping overall calories and/or weight down. Yet Americans’ caloric intake just kept going up and up and up, until recently.

It would be nice to think that this is evidence of Americans finally taking a more holistic approach to diet, and following author Michael Pollan’s famous 2007 advice of, “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” But vegetable consumption actually seems to have been declining in the U.S., and analyses of the recent drop in caloric intake have found that it was driven mainly by a sharp drop in consumption of high-calorie beverages — soft drinks and also fruit juice — especially among children.

Somewhat contrary to recent claims of a cover-up of the dangers of sugar, warnings against sugar consumption have been a staple of official dietary advice since at least 1977. But they weren’t the focus as long as combating heart disease was the top priority. It isn’t really anymore. Heart disease remains the leading cause of premature death in the U.S., just ahead of cancer. But death rates have plummeted since the 1960s, with improved medical techniques likely playing a bigger role than dietary changes.

Rapidly rising obesity and its consequences, meanwhile, spurred a new sense of alarm among public health officials in the late 1990s and early 2000s that led to concerted campaigns to combat it. Reducing caloric intake was the goal, and the most effective way to get people to reduce their caloric intake was deemed to be persuading them to cut out the “empty calories” of sugar-heavy foods in general and soft drinks in particular. It was a simple message, and it had an impact. Which seems like an important lesson.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Sarah Green Carmichael at sgreencarmic@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.