(Bloomberg Opinion) -- While they’re not the type of hedge funds that have been embroiled in a public battle with the Reddit crowd, distressed-debt investors are quietly having a reckoning of their own.

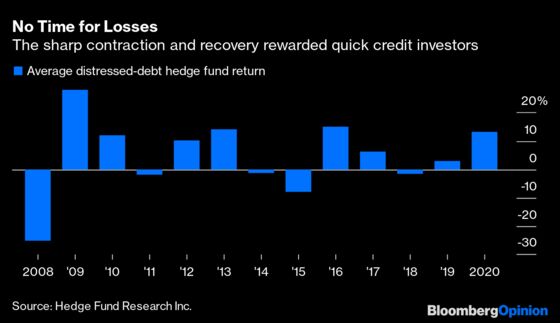

By all accounts, funds that place bets on the hardest-hit companies and segments of the economy had a fantastic 2020, bolstered by aggressive stimulus from both the Federal Reserve and the U.S. government. Distressed-debt funds returned an average of 13% last year, according to Hedge Fund Research Inc., and Bloomberg News reported last month that funds run by firms such as Knighthead Capital Management, Diameter Capital Partners and Apollo Global Management posted gains that were even higher, in some cases approaching 50%. A $2.8 billion fund from KKR & Co. raised at the height of the Covid-19 crisis returned 52%. A $3 billion credit fund that Centerbridge Partners began investing around the same time soared by an annualized 90%.

Even in real time, this kind of performance wasn’t hard to see coming simply because of the huge amount of cash chasing the strategy. On March 31, a week after the Fed revealed an unprecedented intervention to thaw credit markets, I wrote about the sudden boom in new credit funds and argued that they needed to raise cash fast or else risk being too slow to capture the highest returns. At that time, Preqin data suggested distressed-debt funds had $63.6 billion of so-called dry powder to invest. And they did just that: The all-in yield on the Bloomberg Barclays index of triple-C rated corporate debt fell from 19.45% in late March to just 11% by early June.

The issue now for distressed-debt funds is that the rally hasn’t stopped. Triple-C rated U.S. junk bonds gained an additional 1.5% in January, the 10th consecutive month of positive returns and one of the longest winning streaks ever. On Jan. 21, the average triple-C yield fell to 6.42%, a record low. Again, at the peak of the Covid-19 crisis, that yield reached almost 20%. During the 2008 financial crisis, it topped 30% and remained above 15% even after the U.S. recession ended.

In March, the amount of bonds and loans trading at distressed levels in the U.S. quadrupled in less than a week to almost $1 trillion, just about reaching the 2008 peak. This week, a report from S&P Global Ratings found that the U.S. distress ratio — the proportion of speculative-grade securities that yield at least 10 percentage points above Treasuries — fell to just 5% in December, the lowest since 2014.

Those figures understate the slim pickings at the moment for buyers of distressed debt. During the worst of 2020’s market meltdown, several of Ford Motor Co.’s bonds crossed the line into distress. Now, not one of its securities trades at less than 100 cents on the dollar, even though it lost its investment-grade ratings. One of Apollo’s top trades was reportedly buying up beaten-down high-grade debt. Other funds profited by purchasing some desperate early deals while credit markets were still mostly closed, such as Carnival Corp.’s 11.5% coupon bonds at 99 cents on the dollar. The debt last traded at 114 cents, for a double-digit price return on top of double-digit interest payments.

Keep in mind, those Carnival bonds were rated triple-B at the time. The average yield for debt with those ratings now is just 2.13%, according to Bloomberg Barclays data. To get anything approaching what was available several months ago, one of the few options seems to be taking a chance on oil and gas companies, which S&P noted accounts for a quarter of all distressed credits. For example, Great Western Petroleum LLC, which has the lowest triple-C ratings, is marketing $350 million of five-year bonds at double-digit yields to pay off notes maturing in September that now trade at 63.5 cents on the dollar. If the deal goes through, the company’s sponsor said it would inject new equity into the company.

Put plainly, that’s a much dicier proposition than lending to one of the world’s largest cruise-line operators or funding the bankruptcy reorganization of Hertz Global Holdings Inc., one of the biggest car-rental companies. And Great Western is hardly a one-off: Junk-rated U.S. companies issued about $52 billion of debt in January, the third-busiest month ever. According to Bloomberg’s Caleb Mutua, triple-C borrowers accounted for about 21% of those sales; energy represented almost one-third of the total. In a telling quote, David Knutson, head of credit research for the Americas at Schroder Investment Management, told Mutua: “The demand is driven by a desperate need for yield combined with hope.”

That naturally brings to mind the phrase “hope is not a strategy,” even if the frenetic trading in shares of GameStop Corp. and AMC Entertainment Holdings Inc. made Wall Street briefly question that assumption. Then again, entrenched credit investors profited off those wild swings anyway, with Mudrick Capital Management returning 9.8% in January, one of its best months ever, largely thanks to gains on debt and equity options of AMC, to which it had provided $100 million of financing in December.

Smaller investors, on the other hand, have been getting skittish, pulling $1.33 billion from U.S. high-yield funds in the week ended Jan. 27, according to Refinitiv Lipper data. That was the fourth consecutive week of outflows. Meanwhile, U.S. investment-grade bond funds pulled in a staggering $8.3 billion in the week ended Jan. 20, the fourth-largest inflow ever, and followed that up with $6 billion more.

Ultimately, as is often the case with investing in corporate debt, it comes down to a question of whether companies can make it to better economic days. S&P, for its part, says “U.S. corporate defaults are expected to continue to rise as revenue generation pressure is likely to persist, especially for sectors most impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic.” Still, many defaults come in the form of distressed exchanges so firms can avoid or delay bankruptcy. AMC, for instance, was considered in default last month because part of its deal with Mudrick involved converting existing debt into equity.

Weakened companies seem to have any number of choices to avoid folding. That leaves distressed-debt investors with few options but to keep extending lifelines in exchange for potentially lofty returns. There are no other obvious ways to replicate 2020’s performance from simply buying bonds of fallen angels or snapping up the first leveraged loans to hit the post-Covid market.

Howard Marks, the co-founder of Oaktree Capital Group and a legendary distressed-debt buyer, put it this way in a recent memo: “In the past, bargains could be available for the picking, based on readily observable data and basic analysis. Today it seems foolish to think that such things could be found with any level of frequency.” Effectively, the world is more efficient now, he says. “The investment industry is wildly competitive, with tens of thousands of funds managing trillions of dollars … not only is information broadly available and easily accessed, but billions of dollars are spent annually on specialized data and computer systems designed to suss out and act on any discernible dislocation in the marketplace.”

That sure sounds like an investor who feels cornered. Of course, he said something similar in September 2019, lamenting that distressed debt was a struggle because “the economy is too good, the capital markets are too generous. It’s hard for a company to get into trouble.”

Part of this is simply pining for the days of easier profits. But, in theory, the U.S. economy should only improve as more Americans get Covid-19 vaccinations. There’s no reason credit markets would be less receptive than they are right now, given the Fed is in no hurry to tighten policy. So why should anyone expect more lucrative distressed situations to pop up?

Opportunistic credit funds depend on, well, opportunities. While 2020 was full of paths to outsized profits, 2021 looks as if there’s virtually nowhere left for distressed-debt vultures to scavenge.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.