Singapore’s Power Spikes Are the Cost of Clinging to the Past

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Think the cost of electricity in Europe — where fuel shortages and the approach of winter recently drove prices over $200 per megawatt-hour — is crazy? You should check out Singapore.

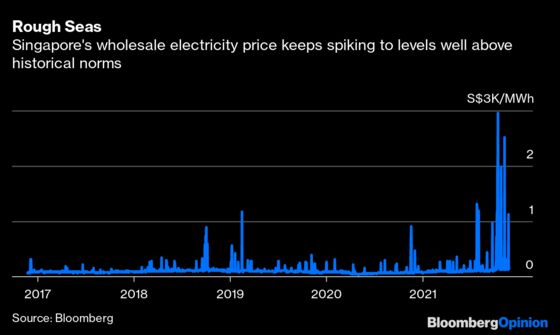

The city-state has seen wholesale prices rising as high as S$2,947 ($2,184)/MWh in October and $1,121/MWh last month. Those levels aren’t even particularly unusual in Singapore’s highly liberalized power market, where costs spike whenever supply and demand fall out of alignment:

While most households pay the fixed government tariff of S$241/MWh, a few that have signed up to prices linked to the wholesale market have been spending extraordinary amounts. At October’s peak, it would cost $5 or more to run a typical oven for an hour.

In Europe and China, the volatile price of grid energy in recent months has often been presented as an outcome of decarbonization. “The world is facing an ever more chaotic energy transition,” Saudi Arabian Oil Co. Chief Executive Officer Amin Nasser told an energy conference in Houston this week, warning of “energy insecurity, rampant inflation, and social unrest” if investment in fossil fuels wasn’t stepped up.

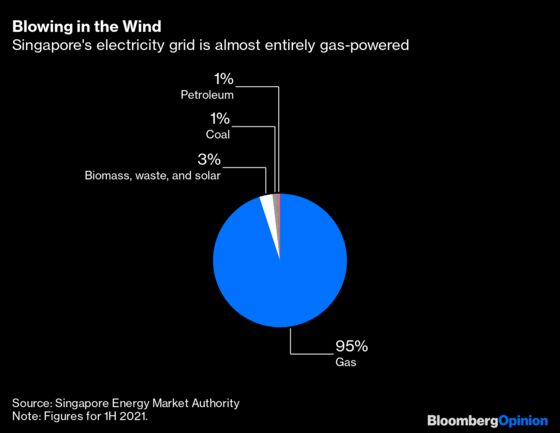

That’s clearly not what’s happening in Singapore, one of the most intensively fossil-fired economies on the planet. Around 95% of electricity is provided by gas turbines, with coal and fuel oil making up another 2% or so. Waste incinerators account for a substantial slice of the remainder, leaving renewable solar and biomass with just 1% or so of generation, next to 47% in Germany and 83% in Brazil.

Instead, it’s a sign of an economy that’s unusually exposed to volatile fuel prices, the same dynamic that’s making power costly in Europe and China, and one thing that a shift toward fixed-tariff renewables ought to alleviate. That transition will be difficult in Singapore, however, because its energy market is an outgrowth of a unique geographic and political situation. About three-quarters of the country is urban and industrial land, meaning there’s simply too little space for large-scale solar or nuclear generation. Wind speeds are slow and water catchments tiny, knocking out wind and hydro, too.

Its relations with neighbors Indonesia and especially Malaysia veer between the cordial and prickly, but the continuing existence of mandatory national service illustrates how nervous the country remains about security. Being dependent on a wire from renewable installations in neighboring states to keep the lights on isn’t an appealing prospect. Billionaires Andrew Forrest and Mike Cannon-Brookes are proposing to build an undersea connection to renewable power plants in northwest Australia, but it’s not clear that such a connection would be possible with current technology.

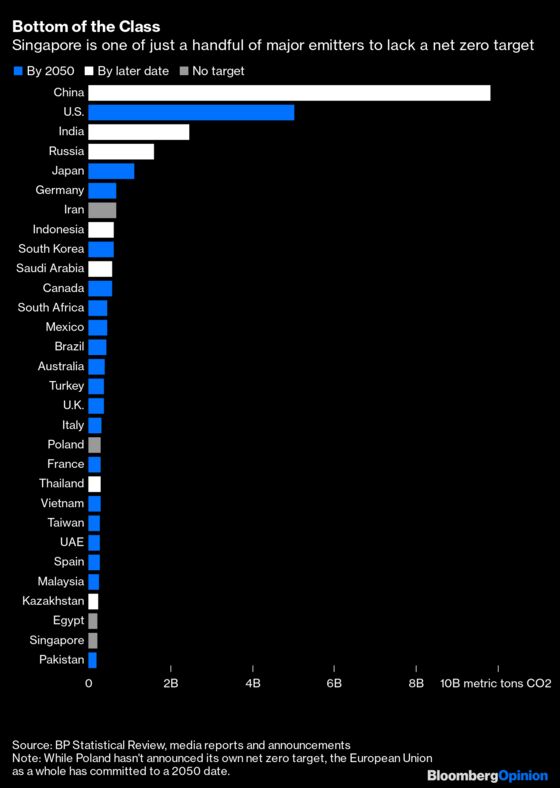

Little wonder, then, that Singapore joins Iran, Poland and Egypt among the top 30 emitters as a rare country not to have committed to any firm phase-out date for carbon emissions (the official line is this will happen “as soon as viable in the second half of the century”). That status is even more remarkable given that Singapore is incongruously a member of the Small Island Developing States grouping at the United Nations, a designation that brings together the mostly poor countries at greatest risk of rising sea levels.

Given the geopolitical constraints and the country’s role as a hub for the shipping and aviation industries, imported fuel is likely to be at the heart of the energy mix for decades to come.

That does suggest one opening, however. There’s a new zero-carbon fuel on the horizon that’s attracted $130 billion of announced investments in recent years — hydrogen. Along with its more easily transportable derivatives of ammonia and methanol, it’s being pitched as a solution to decarbonize a host of industrial activities, from steel, plastics and fertilizer production to fuel for ships, aircraft and long-distance trucks.

A-P Moller-Maersk A/S in August put in an order for eight methanol-powered container ships to start delivery in 2024. Australia’s government wants to bring the cost of green hydrogen down to A$2 ($1.43) per kilogram by 2030 and Asia’s richest man Mukesh Ambani believes India can achieve $1/kilogram by the same date. Those levels would be sufficient to compete with long-term LNG contract costs of around $7 per million British thermal units, not to mention current extreme spot prices in Asia of $35.15/mmbtu.

Singapore’s absence from this race has been notable. Of around $11.5 billion of annual subsidies available to hydrogen development over the coming decade tracked by BloombergNEF, the city-state isn’t providing a cent. A government study of hydrogen options published earlier this year carried many suggestions, but made few promises. With the exception of a few small-scale trial projects with Japanese and Australian partners, there’s little progress on getting projects up and running.

That's a mistake. From its founding, Singapore has shown great foresight in leveraging its position at the heart of the world’s transport networks with visionary large-scale investments in aviation, port infrastructure and oil refining. In this latest industrial revolution, it risks being left behind.

More From Other Writers at Bloomberg Opinion:

- Just How Clean Can Two Billionaires Be?: Mukherjee & Trivedi

- There’s No Such Thing as Secure Energy: Liam Denning

- The Missing Piece of the Hydrogen Puzzle: Clara Ferreira Marques

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.