DeSantis’s Move on Solar Is a Political Calculation

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- When even the Magic Kingdom isn’t safe in Florida, I suppose boring old utilities have no chance.

Having unexpectedly jabbed Mickey & Co. in the eye, Governor Ron DeSantis threw another curveball late Wednesday by vetoing House Bill 741. This would have severely curtailed subsidies for rooftop solar power in the state, plus opened the way for utilities to levy new charges on it. It is as utility-friendly a piece of legislation as possible in a state known for backing its utilities. It also scratches a certain anti-green itch some Republicans have. Nonetheless, DeSantis defied Florida’s Republican-controlled legislature and tossed it.

It’s an odd move and here are three initial thoughts on why.

First, there is the wording of DeSantis’s veto. Referring to the charges that would have been imposed, he wrote:

Given that the United States is experiencing its worst inflation in 40 years and that consumers have seen steep increases in the price of gas and groceries, as well as escalating bills, the state of Florida should not contribute to the financial crunch that our citizens are experiencing.

That’s what you call some context.

DeSantis’s recent salvo against Walt Disney Co. — or, as it turns out, mostly Floridian taxpayers — was a performative T-bone for Republicans not just in his home state but across the country. A governor stood up to a “woke” corporation that had the temerity to criticize that other bit of red meat, the Parental Rights in Education Bill.

The next presidential election is in two and a half years, by the way.

Similarly, although the solar bill ticked some boxes in Florida, blocking it might tick boxes in many other states. Emphasizing broad inflationary pressures, for example, is a great line of attack on an incumbent president, if one were so minded. It also indicates sympathy for voters nationwide.

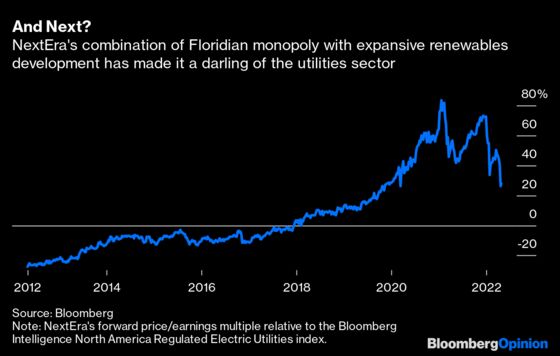

Second, the state’s biggest utility, Florida Power & Light, is owned by NextEra Energy Inc. NextEra is the biggest utility in the world by market cap and has long traded at a premium to its U.S. peers. This is because it combines a well-run regulated utility in its utility-friendly home state with a huge and growing unregulated renewables business across many other states. In a nutshell, NextEra is fortress Florida plus a series of green beachheads in everyone else’s backyards.

Now fortress Florida looks a bit less secure. Moreover, DeSantis’s move follows on the heels of another governmental setback, this time in Washington. An obscure but possibly devastating investigation into solar-panel imports by the Commerce Department has the potential to slam the brakes on the U.S. solar boom (see this). NextEra is by far the biggest solar-project owner in the U.S. — which is why this risk featured so prominently on the company’s recent earnings call.

Jim Robo, the long-time chief executive officer who built NextEra into a behemoth, announced he was stepping down from that role in late January, which looks like fortunate timing. But that unsettled investors and the news has since become more unsettling. NextEra’s traditional premium has taken a big tumble.

Third, while solar advocates cheered DeSantis’s unexpected restraint Wednesday, they may want to temper their joy. As I surmised, his political calculus probably does not reflect any passion for solar power — crazy as that might seem in a Sunshine State horribly exposed to rising sea levels and where distributed energy systems offer insurance against hurricane damage to the grid. Having established his inflation-fighting credentials, and probably winning November’s gubernatorial race, DeSantis may well sign some future version of HB741 and also adopt some form of drill-baby-drill energy policy ahead of 2024. Moreover, even if Florida’s solar advocates have dodged higher charges for now, they, like NextEra, must still contend with that Commerce Department investigation. Subsidies go only so far if panels are suddenly more expensive or altogether unobtainable.

NextEra’s peers should also pause before cheering this surprise move from Florida man-in-chief. Utilities make money primarily as a function of how much they invest, earning a regulated return. That investment has risen at a rapid clip, with the industry’s aggregate electric “rate base” — the assets on which they earn a regulated return — expanding by almost 7% a year on average since 2010, according to Hugh Wynne, an analyst at Sector & Sovereign Research LLC. Yet customer bills have gone up by only about 0.5% a year.

The reason: low inflation and, in particular, the collapse in natural gas prices, which reduced the cost of electricity. But those factors have now reversed, as DeSantis pointed out. Looking ahead, as utilities seek to recover similar increases in investment, they will have to persuade state regulators to allow much bigger additions to customer bills. Along with higher gas prices, inflation will boost the cost of everything from metals for transmission lines to the wages of workers who put them up. In addition, rising Treasury yields squeeze the spread that utilities have enjoyed on their regulated rates of return and put pressure on stock prices as investors adjust their expectations for dividend yields. For utilities, the world has changed.

Ironically, this could carry a silver lining for NextEra. Regulators have, over the years, stymied several of its attempts to buy utilities in other states. But as customer bills rise, so does the need for greater efficiency, and NextEra has a reputation for efficiency that regulators might now view more favorably. DeSantis’s hawkishness may contain more than a touch of grandstanding, but energy inflation is real.

More from Bloomberg Opinion:

- Solar Power Is Winning From the Energy Crisis: David Fickling

- Russia’s War Draws Governments Into Energy Markets: Liam Denning

- The Solar Farm That Almost Destroyed a Town: Francis Wilkinson

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.