(Bloomberg Opinion) -- A declining population is generally seen as a sign that a city isn’t doing so well. But with overall population growth slowing in the U.S. (and already turning to decline in some countries in Europe and Asia), more and more cities and metropolitan areas will shrink. Will that mean they’re all failing?

There is a growing academic literature (most of it sequestered behind paywalls, I’m afraid) on the topic of shrinking cities that is aimed at least partly at answering this question — and the emerging answer seems to be that no, shrinking isn’t always bad.

Dutch researcher Ellis Delken, for example, compared happiness-survey scores in German cities and rural districts that had shrunk, grown or remained stable in population from 1990 through 2005, and found that residents of shrinking areas were on average happier than those in growing ones. In the U.S., Tufts University professor of urban and environmental policy and planning Justin Hollander looked at “neighborhood quality” scores in 38 big U.S. cities in the 1990s and 2000s from the Census Bureau’s American Housing Survey, and found that while growing cities scored higher than shrinking ones on average, there was a lot of heterogeneity, with residents of several cities that lost population over the study period (Atlanta, Boston, Minneapolis, New Orleans) giving high and rising neighborhood ratings.

Such surveys suffer from the limitation that, as Delken put it near the end of her paper, “the people that have left the shrinking cities did not take part in this study,” but they do indicate that life for those that stay behind can be perfectly pleasant (in the German shrinking cities, people reported being especially happy about public transportation and the standard of living). There are also lots of shrinking cities where those who stay behind are quite affluent: A brand-new article by Maxwell Hartt, a lecturer in spatial planning at Cardiff University in Wales, looks at the 886 U.S. cities with 10,000 residents or more as of 2010 where population had peaked before that year, and finds that 27 percent of them had average incomes higher than those of their surrounding regions.

Most of these 238 “prosperous shrinking cities,” as Hartt calls them, are wealthy suburbs. I grew up in one of them: Lafayette, California. It is in a metropolitan area — San Francisco-Oakland-Hayward — that saw a 33% population increase from 1980 to 2010, and in a county that grew 60%. But Lafayette effectively chose to shrink as residents resisted denser new development and stayed in their big houses long after the kids moved away, behavior encouraged by California’s Proposition 13-imposed property tax rules. These older residents have in recent years proved to be mortal, though, and according to Census Bureau estimates, Lafayette’s population has grown more than 10% since the 2010 census (to a new peak of 26,440 as of July 2017) as families with kids have moved into the houses that longtime Lafayettans finally vacated.

So that’s one formerly shrinking city’s not-exactly-helpful story. In the regressions Hartt ran on the whole group of shrinking cities, what stood out most about the prosperous ones was their high talent levels (as measured by the percentage of residents with bachelor’s degrees) and low levels of income inequality (because non-affluent people don’t live there) relative to surrounding regions. Again, maybe not the most useful and encouraging information for most places suffering from involuntary population loss, although I look forward to seeing where Hartt’s further research on this subject leads him.

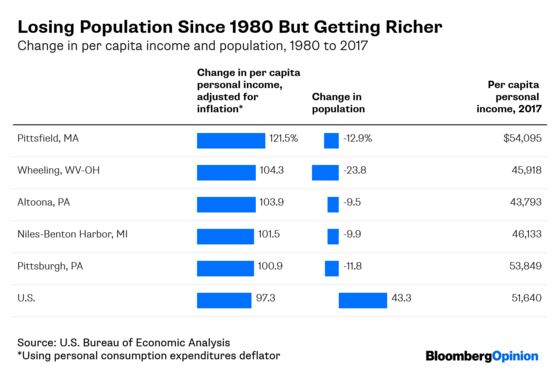

It has already led me to conduct my own quick-and-dirty research project, in which I set out to identify prosperous shrinking metropolitan statistical areas, the federal-government-defined concoctions of one or more counties with “core urban areas” of at least 50,000 residents. This approach has the advantage of avoiding the shrinking swanky suburb phenomenon. The criteria I chose also delivered too few results for a meaningful regression analysis, but for an opinion columnist, that’s kind of an advantage, too. Using data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, which has annual population estimates for metropolitan areas that adjust for changes over time in metropolitan-area delineations, I identified 45 U.S. metro areas that had lost population since 1980 — a period during which the country as a whole grew by 43% — and threw out all the ones where per capita personal income growth trailed the national average. Here’s what was left:

Another way to sift out “prosperous” shrinking metropolitan areas might be to look at those where 2017 per capita income exceeded the national average. Along with Pittsfield and Pittsburgh, which are both on the above chart (and both named for 18th-century British statesman William Pitt, for whatever that’s worth), the only other shrinking metro area to make that cut is Cleveland-Elyria, Ohio, with a per capita income of $51,755. Use the BEA’s real per capita personal income estimates for 2017, which were just released and account for differences in purchasing power among metropolitan areas, and seven more areas (including Wheeling and Niles-Benton Harbor from the above chart) make the cut. But those data are only available back to 2008 and this all seems complicated enough already, so … let’s just leave it.

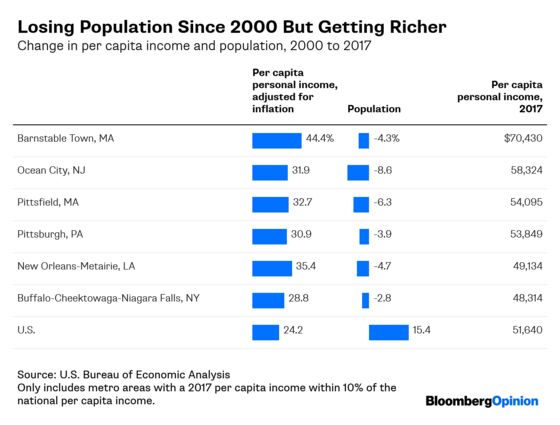

To get another view, I looked at the metropolitan areas that have lost population since 2000. Interestingly, given that overall U.S. population growth has been much slower since 2000, there are also 45 of those. Nineteen of them, or 42%, saw per capita personal income rise at a faster pace than the nation. I somewhat arbitrarily divided these into the 13 with 2017 per capita incomes of less than 90% of the national average and the relatively richer remainder. The members of the first group are all on the small side, and all but three can be found in a narrow, hilly 500-mile-long swath of territory from southern West Virginia to upstate New York: Beckley, West Virginia; Cumberland, Maryland-West Virginia; Huntington-Ashland, West Virginia-Kentucky-Ohio; Weirton-Steubenville and Wheeling, West Virginia-Ohio; Altoona, Johnstown and Williamsport, Pennsylvania; Elmira and Utica-Rome, New York; Danville, Illinois; Niles-Benton Harbor, Michigan; and Pine Bluff, Arkansas.

What’s going on with most of these areas is, I imagine, a combination of being down so long that it looks like up, and largely missing out on the two phenomena that threw so many regional economies for a loop in the 2000s: the “China shock” that hammered until-then-still-chugging manufacturing industries in parts of the South and Midwest, and the real estate bubble and bust that hit hardest in parts of the Sun Belt. Also, as Tim Henderson of Pew Charitable Trusts’ Stateline news service reported after doing a similar crunching of numbers last year, much of the income growth in such metros (he was referring specifically to Huntington, but I imagine it applies more broadly) comes from “raises in Social Security, disability insurance and other government payments.”

For the richer six, the stories seem more interesting, if also not always inspiring.

Topping the income-growth and income rankings are the Barnstable Town metro area, better known as Cape Cod; metro Ocean City, which stretches north from Cape May in the southeastern corner of New Jersey; and metro Pittsfield, aka the Berkshires. They’re all scenic areas where lots of affluent people have summer homes and some choose to stick around for the whole year when they retire, while younger working families can find it hard to gain a foothold. “Cape Cod is running a social experiment about whether you can have a society without children,” a local economist told the New York Times a few years ago. It’s not quite that dire in and around Ocean City or Pittsfield and, as I wrote in a column in December, the Berkshires model of rebuilding a formerly manufacturing-centered economy around arts and education does offer some possible pointers for other areas, but on the whole the summer-home approach to prospering amidst population decline seems both limited in application and possibly unsustainable.

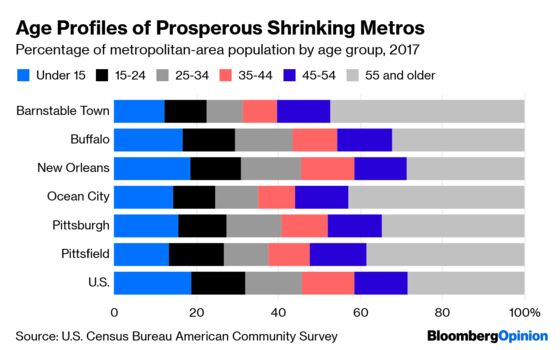

To see this a little more clearly, here are the age distributions for all six metropolitan areas:

All of the prosperous shrinking metropolitan areas skew old except for the New Orleans area, which has an age distribution quite similar to the nation’s. That’s probably because it’s not so much a shrinking metropolitan area as an area that has gained population every year since 1990 except one — but shrank a whole lot that one year. Hurricane Katrina devastated the region in August 2005, and by July 2006 the metro area’s population had declined an estimated 25%, with lower-income residents (whose neighborhoods tended to be the worst-hit by flooding) overrepresented among the departees. Some have since come back, the city has attracted a few young creative types from elsewhere, the oil and gas industry has been resurgent, and New Orleans is an ever-bigger tourist draw. So that’s a unique case!

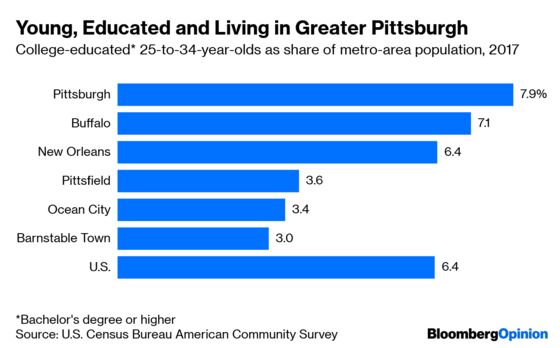

Pittsburgh and Buffalo, on the other hand, would seem to offer at least a little hope for other shrinking cities in the Rust Belt and elsewhere. The cities themselves more or less stopped growing in the 1930s, and started shrinking outright in the 1950s. For the metropolitan areas, the population declines started in the early 1970s and have continued, with occasional pauses, ever since. Both areas have populations that skew old, but that’s due not to a recent influx of oldsters but a decades-long lack of influx of anybody else. Now, though, both regions can boast reasonably healthy shares of people early in their working years. If you look at those young people’s educational backgrounds, metro Pittsburgh and Buffalo really stand out.

The equivalent percentages for metropolitan San Francisco and San Jose are 11.6% and 12.2%, so Pittsburgh and Buffalo aren’t exactly global magnets for young talent just yet. But they do seem to have become regional magnets — in a region that, some recent research has shown, has been experiencing a “brain gain” relative to the large cities of the Sun Belt. In Pittsburgh’s case this revival, centered in the city proper, has already gotten so much attention in the national media that I was moved to write a disparaging piece about it in 2016, which I must admit I regret a little now. In Buffalo the city itself is still struggling (30.9% of the population is below the poverty line, versus 22% in Pittsburgh and 12.3% nationwide) and talk of a revival remains relatively muted. Like Pittsburgh, though, it has assets — universities, cultural institutions, big-league sports teams, great architecture — that it was able to hold onto during the long decline, and unlike Pittsburgh, it’s next to the economic powerhouse that is southern Ontario.

The next stage for Pittsburgh and Buffalo might be an end to population declines, meaning they would no longer be prosperous shrinking cities. The most oft-cited success story in the shrinking-city literature is probably Leipzig in eastern Germany, which started losing population in the 1930s, lost its industrial base after the reunification of Germany in the 1990s, and was lauded by Harvard economist Edward Glaeser in his 2011 book “Triumph of the City” for its “hardheaded policy of accepting decline and reducing the empty housing stock.” Since then, Leipzig has become the nation’s fastest-growing large city, and is even struggling with a housing shortage. As overall population growth slows, sharp turnarounds like that are presumably going to get rarer. From that perspective, where the Pittsburgh and Buffalo metropolitan areas are right now already looks pretty good.

My father excepted. Hi, Dad!

The seven are, in descending order of real per-capita income, Wheeling, WV-OH; Decatur, IL; Davenport-Moline-Rock Island, IA-IL; Detroit-Warren-Dearborn, MI; Peoria, IL; Niles-Benton Harbor, MI; and New Orleans-Metairie, LA.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.