(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, the boom in trading activity among retail investors has been stunning. This flurry of activity was driven in no small part by companies like Robinhood Markets Inc., which seized on the fact that younger people were stuck at home to offer them a fun way to make money.

That last part — making money — was contingent on stocks and other risky assets continuing to rise. For the better part of the past year and a half, that hasn’t been a problem: From April 2020 through August, the S&P 500 Index posted a monthly decline only three times, and never more than 4%. And that’s to say nothing of the lucrative opportunities trading the hottest cryptocurrencies of the day or placing options bets on meme stocks like GameStop Corp. and AMC Entertainment Holdings Inc.

It’s getting tougher out there for the Robinhood crowd. U.S. stocks are coming off their steepest weekly decline since February and the biggest monthly loss since March 2020, with the S&P 500 tumbling again on Monday to its lowest level since July. Bitcoin has failed to come close to its April high of almost $65,000. And shares of GameStop and AMC are languishing, seemingly losing their meme magic — most investors who bought over the past four months and are still holding them are sitting on losses.

What happens when an app is no longer fun? It’s forgotten.

That seems to be what’s happening lately with Robinhood. JPMorgan Chase & Co. analysts said in a report last week that the trading app’s downloads fell 78% in the third quarter compared with the previous three months, based on tracking data from Apptopia. The company’s daily active users most likely dropped by 40% in the period. The decline is happening on other platforms, too, with Charles Schwab Corp.’s daily users slipping by 30% and crypto apps like Coinbase Global Inc. also experiencing a slowdown.

This could prove to be just a blip, of course. But the way in which fintech disruptors have removed almost all friction from the financial system increases the risk that a more prolonged decline in markets could have noticeable spillover effects for the real economy.

Robinhood’s mission statement is to “democratize finance for all,” leading the charge to bring fees on trading stocks and exchange-traded funds to zero. This is a clear victory for retail investors, knocking down a barrier to putting even small sums of cash in diversified equity indexes that will all but certainly increase in the long run.

But then there’s options trading, which also comes at no cost at brokerages including Robinhood. These derivatives are inherently short term and speculative in nature, with call options in particular offering tremendous upside during rallies but also the risk of expiring worthless. During the first bout of meme-stock mania in January, traders who bought or sold 10 or fewer contracts at a time were out in force, even more than when they were pushing technology company shares to records in the late summer of 2020.

Those small investors who have reliably bought every dip seem spooked by this most recent one. Bloomberg News’s Katie Greifeld reported that retail traders spent just 43% of their total volume in the options market on bullish calls in the week through Sept. 24. That’s the lowest share devoted to call options so far in 2021, according to Sundial Capital Research.

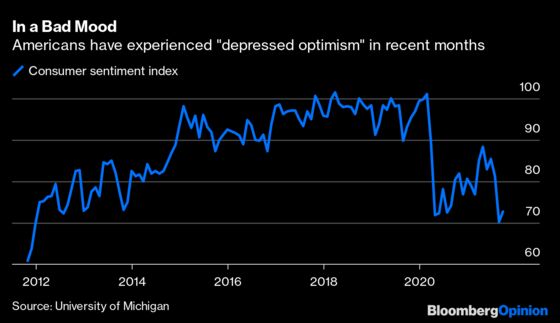

It doesn’t take much squinting to see how this souring mood on stocks could alter the trajectory of the world’s largest economy. The University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index managed only a modest rebound in September from the lowest level in almost a decade. Richard Curtin, director of the survey, called it “depressed optimism,” which was “initially sparked by the delta variant and supported by a surge in inflation and unfavorable long-term prospects for the national economy.”

I don’t doubt any part of that rationale. But I also can’t help but notice that the sentiment index reached the highest since the start of the pandemic in April, which was during a period of ramped-up vaccinations but also coincided with a two-month gain of almost 10% in the S&P 500. Elevated inflation always stings — but it feels much less noticeable during a period of double-digit asset growth. By contrast, in the five months through September, the equity benchmark rose by only 3%, with last month’s losses taking a big bite out of overall performance.

At least for now, consumers haven’t drastically changed their behavior. U.S. Commerce Department data released Friday showed personal spending rose 0.8% in August and 0.4% on an inflation-adjusted basis, both in line with estimates, though July’s figures were revised lower to -0.1% and -0.5%, respectively. Still, that was enough to sharply lower the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s GDPNow forecast to a 2.27% expected expansion in the third quarter.

A popular saying is that the stock market is not the economy. That may be, but I’d caution that there’s never before been a time when the very same Americans who are needed to power U.S. growth also have such unfettered access to financial markets. It’s one thing for the “wealth effect” of higher asset prices to drive sentiment among wealthy individuals, who won’t alter spending based on stocks falling by a few percentage points. It’s quite another if people across income brackets have been conditioned to count on the valuations of Alphabet Inc., Amazon.com Inc. and Apple Inc. reaching nosebleed levels and aren’t accustomed to seeing balances decline. Robinhood, meanwhile, is looking for ways to keep its users hooked: Planned features include allowing them to receive paychecks by direct deposit up to two days early and letting them invest spare change in specific stocks.

It’s great that Robinhood and other fintech companies want to democratize finance, but it’s worth acknowledging the risks posed by the lack of friction in today’s financial system. Just as there were no brakes as equities reached record after record in August, it’s worth wondering if the same is true on the downside amid the persistent selling pressure of the past few weeks. Momentum is hardly a new phenomenon in investing, but with so many newbies involved, there’s reason to suspect it’ll be a stronger driving force than ever before.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.