Critics of Economics Fight a War That Ended Long Ago

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Each year brings a reliable drumbeat of broadsides against the economics profession in the popular press. This year’s standout is an op-ed by anthropologist David Graeber in the New York Review of Books. Like its many predecessors, Graeber’s article gets a few things right and a lot of things wrong about the failings of economics and its role in the modern world.

Like many of his fellow critics, Graeber focuses almost entirely on one particular branch of economics -- business cycle theory, which occupies a small niche in the broad field of economics. A list of all the other topics economists study would be too long for one column, but it includes things like inequality, economic mobility, wage policy, taxation, unions, health, education, poverty, economic development, race, gender and a vast host of other things that are important to people’s lives and livelihoods. To ignore these as Graeber does, and to declare economics “no longer fit for purpose” because of the shortcomings of business cycle theory, is like declaring biology obsolete because of the failure to cure cancer.

That’s one reason that sentences like the following seem hopelessly out of touch:

Economists still teach their students that the primary economic role of government—many would insist, its only really proper economic role—is to guarantee price stability.

By saying this, Graeber erases the entire field of public economics, which studies government policy. But even just regarding business cycle theory, his assertion is simply wrong. Mainstream macroeconomic models don’t just care about inflation; they emphasize a balance between price stability and economic output. According to these models, which are used by central banks around the world, one of the government’s primary roles is to prevent unemployment from rising.

We saw this a decade ago when central bankers went to great lengths to reduce unemployment by cutting interest rates to zero or below and unleashing enormous quantitative easing. They did so in spite of dire warnings that monetary easing would cause inflation to rise. Some would argue that it was their quick and decisive action that staved off a replay of the Great Depression.

It is true, as Graeber says, that economists don’t have a strong understanding of inflation. Those who predicted a big rise in prices as a result of quantitative easing were proved wrong. The Phillips curve, which represents a trade-off between unemployment and inflation, may or may not even exist; a vigorous debate continues. And there is little consensus regarding the causes of rare but devastating episodes of hyperinflation, such as the one now impoverishing the people of Venezuela.

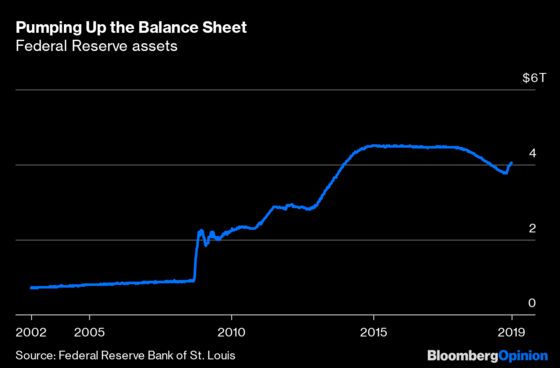

Graeber spends a lot of time heaping scorn upon the quantity theory of money, a simple and rather outdated idea that gained popularity during the high inflation of the 1970s. Central bankers tried controlling the money supply from 1979 to 1982, but abandoned the effort when they discovered that it was beyond their control. Nowadays they target interest rates instead, as well as using unconventional tools like quantitative easing. The Federal Reserve had few compunctions about dramatically expanding its balance sheet -- which requires pumping money into the economy -- during the Great Recession:

The Bank of England had even fewer reservations, quintupling the size of its balance sheet between 2007 and 2012. It’s possible that doing even more would have brought even better results and that a fear of inflation held back even more dramatic action. It’s quite reasonable to assert that lingering fear of inflation has too strong a hold on the minds of economists and policy makers. But the dramatic and sudden change in central bank balance sheets belies Graeber’s assertion that hard-money policies are regarded as “a matter of principle” or “universal common sense” by the powers that be.

About one thing Graeber is certainly right: modern business cycle theory does resemble a “shed full of broken tools.” Many of the assumptions baked into most macroeconomic models are either provably false or highly improbable. This renders macroeconomic models of very limited use in a crisis; quantitative easing was an impromptu, seat-of-the-pants policy, and many central bankers reverted to older and simpler models when crunch time came. Macroeconomists are very far from a general understanding of how recessions and inflation work; many younger scholars are going back to the drawing board, studying the nitty-gritty details of how consumers and businesses behave in the hope that one day a better theory can be constructed.

But in the meantime, Graeber and the rest of the long parade of intellectuals lining up to denounce economics seem to have little in the way of credible alternatives. Heaping scorn upon the discredited theories of the past is fine, but it offers little practical guide to the future. There are plenty of good and constructive criticisms to be made of economics, and especially of business cycle theory, but caricaturing what economists do and believe is not helpful.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.