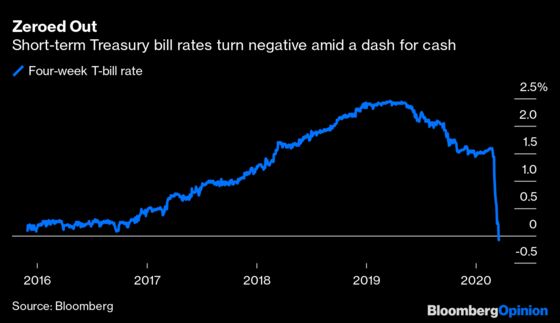

Dash for Cash Pushes Treasury Bill Rates Below Zero

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Negative yields have reached America’s shores. Well, sort of.

The rate on one-month U.S. Treasury bills dropped as low as -0.089% on Wednesday, and the rate on those maturing in three months sank 15 basis points to -0.0178%, data compiled by Bloomberg show. Six-month bills came close to dropping below zero, too. This has happened before when the Federal Reserve locks its benchmark near the zero lower bound: the one-month bill reached a record low -0.091% in December 2008 and the three-month touched -0.0508% in October 2015.

But for it to happen on a day when longer-term Treasury yields climbed, stocks sank to the lowest levels in three years and both investment-grade and high-yield corporate bonds tumbled suggests the dash for cash is so intense that the price doesn’t matter. Indeed, money-market funds pulled in $143.2 billion in the past two weeks, an unprecedented sum since Investment Company Institute data began in 2007. With the funds now holding $3.78 trillion, just shy of their post-crisis high, it’s tempting to wonder just how low rates can go below zero and whether longer-term debt might follow soon.

For Treasury bills with such short maturities, it’s fairly straightforward why a combination of huge private demand coupled with Federal Reserve purchases drives their rates below zero. Unlike longer-term debt, which offers semi-annual interest payments, T-bills have no coupon and are sold based on an upfront discount rate. So when the rate turns negative, it simply means investors are willing to pay slightly more than face value for the bills — say, $10,001 for a T-bill that will pay $10,000 in three months.

In the past, that might have seemed nonsensical. But I’d wager most readers were entirely unfazed by that example. The negative-yield experiments in Europe and Japan have normalized this type of trade-off between guaranteed losses on government-backed debt if held to maturity and the risk of losing even more money elsewhere.

For the near future, it seems unlikely that negative yields will spread further along the U.S. curve. But interestingly, a Bloomberg monitor of outstanding Treasuries quoted some coupon-bearing debt with ultra-short maturities as having slightly negative yields. It’s unclear whether those are actual tradable levels or just reflect the currently distorted bid-ask spreads across the world’s biggest bond market. But that’s a development worth keeping an eye on.

The Fed, for its part, has repeatedly dismissed the idea of negative yields. “We do not see negative policy rates as likely to be an appropriate policy response here in the United States,” Chair Jerome Powell said Sunday after the central bank slashed its benchmark lending rate to near-zero.

That’s never the end of the story for bond traders, of course. If they grew convinced that the Fed would lower rates below zero, they’d be out ahead of that move, pricing it into fed funds futures and other short-term rates markets. That doesn’t seem to be what’s happening now: The lowest implied rate in the fed funds futures market is 0.08% later this year.

Even if negative yields aren’t imminent, it still doesn’t feel good to see this kind of scramble for cash. Markets are in turmoil, and, unlike just a few weeks ago, so is the financial system. With millions of Americans stuck in their homes and thinking about worst-case scenarios, it’s hardly a surprise they’d want to get off the market roller coaster.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.