(Bloomberg Opinion) -- You might think that a government report declaring the conduct of a major casino as “illegal, dishonest, unethical and exploitative” and “in a word, disgraceful” would be bad news for shareholders in the business. Judging by the jump of as much as 13% on Tuesday in shares of Crown Resorts Ltd., it’s anything but.

That’s not as surprising as it may seem. After all, the main problem for Crown after an official inquiry by Australia’s Victoria state found evidence of money laundering, exploitation of problem gamblers, and misleading of regulators at its Melbourne casino was the seemingly indelible stain on its reputation.

The key recommendation of the latest report — following initial revelations published in the Age and Sydney Morning Herald newspapers in 2019, and a separate inquiry by New South Wales state in February — was that a “Special Manager” be given the power to oversee the casino’s operations for two years. That will ensure a trusted government-appointed figure will have the responsibility of cleaning up Crown’s image.

For all that businesses hate the meddling of regulators in their affairs, the arrival of legions of interfering compliance officers can be strikingly good for the bottom line. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. took just over a year during the 2008 global financial crisis to quadruple in value and return to a near-record market capitalization over $100 billion. JPMorgan Chase & Co. saw its market cap triple over roughly the same period.

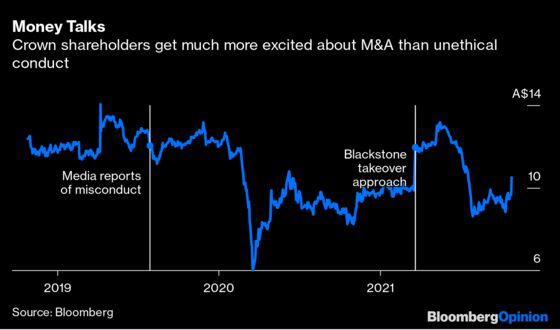

There’s ample evidence that investors react negatively to news of unethical behavior — not least in Crown’s own stock price, which fell by 8% in the two weeks after the initial newspaper reports. By the same token, events likely to lead to an improvement in business ethics ought to be good for equity valuations.

That’s even more the case for a casino. As a regulated monopoly that typically pays Victoria more than A$200 million ($150 million) a year in gambling taxes, Crown is a golden egg-laying goose that the government has no interest in killing. The final decision in the Victorian inquiry, the commissioner Ray Finkelstein wrote, “required the weighing up of two almost irreconcilable positions”:

On one side, there was the overriding need to maintain the integrity of the licensing system. That requires the cancellation of a casino license held by an unsuitable person. On the other side, there were two factors: the risk that cancellation of Crown Melbourne’s license would cause considerable harm to the Victorian economy and innocent parties; and whether, in a short time, Crown Melbourne could so ‘remake’ itself that it would again become suitable to hold a casino license.

It’s telling that in balancing these two priorities, Finkelstein ultimately came down on the side of keeping the resort in business. No party has any interest in an outcome so punitive that Melbourne is left with an empty hulk of a casino on the south bank of the Yarra River. The question then becomes whether the casino’s road back to redemption is an uncertain one, where the business regulates itself with a watchful eye over its shoulder in case it oversteps the boundaries — or the more interventionist approach, where the government is so involved in the process that it more or less guarantees the outcome.

To be sure, it’s possible that a two-year overhaul won’t be enough to fix Crown Melbourne’s problems. As the numerous and repeated instances of the casino industry getting mixed up with money laundering and organized crime demonstrate, one of the core jobs in running a gambling business is walking that narrow line between ethical and unethical conduct without embarrassing your host government enough to lose your license.

In theory, though, it shouldn’t be impossible to make money when house winnings account for about 1.35% of the $32 billion of wagers made by high rollers in a good year, not to mention the rivers of cash flowing from conventional gaming tables, machines, restaurants, entertainment venues and shops. If the government is unable to find anyone who can run Crown Melbourne with integrity while still turning a profit, what would that say about the viability of an ethical casino industry as a whole?

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.