Credit Markets Are Full of Alarms and No One Cares

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The credit markets are no place for discerning investors these days.

U.S. junk bond and leveraged loan sales have surpassed $1 trillion in 2021, an unprecedented amount for a calendar year. Loan funds have experienced inflows during all but two weeks this year, bringing the S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loan Price Index close to an all-time high, and year-to-date issuance of collateralized-loan obligations is also at a record. Even municipal-bond buyers are turning to the riskiest corners of the market, plowing $1.2 billion into high-yield muni funds in the week ended Nov. 10, the second-most ever, data from Refinitiv Lipper show.

Simply put, in the world of corporate credit, many companies want to borrow cheaply and a lot of investors are all too willing to lend at rock-bottom rates. This is hardly a new phenomenon, but with signs of deal fatigue finally creeping in at the end of last week ahead of the Thanksgiving holiday and a more subdued December, it’s worth taking a step back to assess the bond market.

When scanning the market, it quickly becomes clear that thanks to the Federal Reserve’s unprecedented intervention in March 2020, combined with its steadfast willingness to tolerate a longer-than-expected stretch of elevated inflation, investors see little choice but to whistle past the graveyard. Risks may be piling up, but haven’t you heard? Distressed debt is dead. In fact, the rampant borrowing hasn’t kept pace with a surge in spending and higher prices: Junk-rated companies have the least debt relative to earnings since 2015.

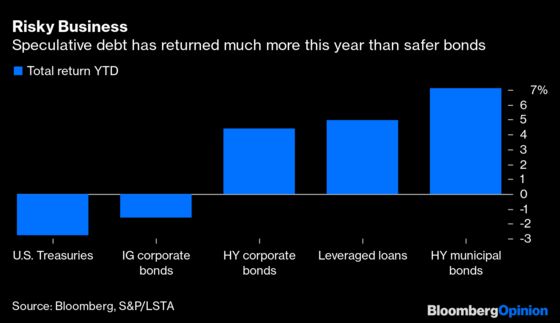

Indeed, with healthy balance sheets across the board, it has clearly paid off to lock in any sort of credit spread in 2021. The Bloomberg U.S. Treasury Index has lost 2.75% so far this year as yields gradually climbed from their pandemic lows. Investment-grade corporate bonds have fared slightly better, dipping 1.6%. But it’s junk bonds, which have gained 4.4%, and leveraged loans, which are up almost 5%, that have been some of the best performers in the public markets.

All the while, Bloomberg News’s credit reporters have been doing an admirable job of flagging the mounting risks, even if the relative performance suggests traders don’t seem to care.

From July: Leveraged Loan Investor Defense ‘Destroyed’ Amid Rampant Demand

80% of new leveraged loans last month gave borrowers the ability to make unlimited investments. That’s up from zero in January and 25% in February.

“Covenants do continue to get worse,” said Pisano. “Every day something comes up that makes them worse.”

From August: Leveraged Loan Boom Pushing Investor Safeguards ‘to the Brink’

Surging investor demand for leveraged loans is fueling a dramatic weakening in creditor protections, with borrowers gaining more leeway to incur additional debt and issue dividend payouts, according to Moody’s Investors Service.

From September: Bond Buyers Raise Risk for Next Rout by Sacrificing Protection

From October: Europe’s Leveraged-Loan Safeguards Shrink in Red-Hot Market

Of course, this sort of erosion in investor protections happens during every period of risk-taking. I wrote about this trend in leveraged loans in August 2018, and in January 2019, and even in February 2020, just days before Covid-19 roiled the global financial system.

But this cycle might go even further. Last week, Bloomberg’s Natalie Harrison reported that private-credit funds, which are much better positioned than public market investors to demand safeguards in return for often being the sole lender on a deal, are increasingly throwing in the towel and agreeing to “covenant-lite” structures as well. Individual and institutional investors alike are rushing to get into the illiquid credit market as an alternative to otherwise paltry corporate-bond yields.

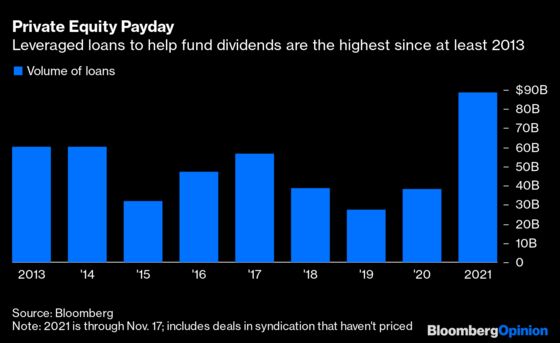

At the same time, private equity firms are piling a record amount of debt on to portfolio companies as a way to pay themselves large dividends. In one of the most extreme examples, Lottomatica SpA, bought by Apollo Global Management Inc. in May, priced a 400 million-euro ($462 million) bond at 8.125% earlier this month, with proceeds earmarked to pay such a large dividend that Apollo will effectively recoup its entire investment. That kind of quick return is increasingly important when private equity giants are raising an unprecedented amount of cash, leaving them “in a state of collective delusion” and paying deal multiples that look “bananas” to beat competitors for acquisitions.

Few would argue that these kinds of maneuvers, fueled by cheap financing, are a healthy development for the broad financial system. Yet it comes back to that gnawing question for investors: What’s the alternative? The average U.S. junk bond yields 4.38%, which is now lower than inflation, whether measured by the consumer price index or the personal consumption expenditures index. It’s even worse for buyers of investment-grade credit. Meanwhile, with negative inflation-adjusted borrowing costs, expect companies to go back to the debt markets again and again, pushing the envelope on what they can get away with.

The elephant in the room is the Fed, which came to the rescue of these very same investors less than two years ago when the onset of the pandemic threatened widespread corporate defaults and caused a stampede out of bond mutual funds. At the time, the central bank did what needed to be done, setting aside moral hazard and establishing the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility to stabilize markets. It is not a coincidence that the S&P 500 never fell below the level it reached the day the new facility was announced.

It’s times like now, when risky assets can seemingly do no wrong, that policy makers should contemplate the cost of moral hazard. The Fed wants to wait until the economy reaches maximum employment before raising interest rates from near zero. But it might also do well to consider that companies owned by private equity firms employ hundreds of thousands of Americans — if their balance sheets are loaded up with debt and they can no longer roll it over cheaply to get by, they’ll need to cut costs somewhere. Layoffs could be a place to start. This calculation also applies to the “zombie companies” that don’t bring in enough cash to cover interest payments. The central bank claims to want to get away from the zero lower bound of interest rates, but a world awash in debt could very well keep them there.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell discussed the idea of “risk management” during his last press conference. For better or worse, until there’s a clear indication that the central bank is truly pivoting in that direction, credit investors need not apply any such risk management of their own.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.