The Fed Has 21 Trillion Reasons to Combat High Inflation

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Anyone who doubts the Federal Reserve will push back against accelerating inflation need only consider the size of the U.S. Treasury market to put their mind at ease.

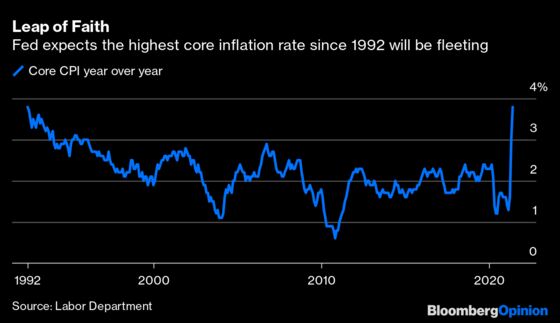

The U.S. consumer price index jumped 5% in May from a year earlier, while core CPI climbed 3.8% in the biggest increase since 1992. Both measures exceeded estimates on a month-over-month basis as well, suggesting that the price pressures in the world’s largest economy aren’t just due to so-called base effects. Though it’s still too soon to say whether Fed officials are right or wrong that this move higher is largely transitory, the figures hammer home why the central bank will likely move forward apace with talking about how to best scale back asset purchases at its meeting next week.

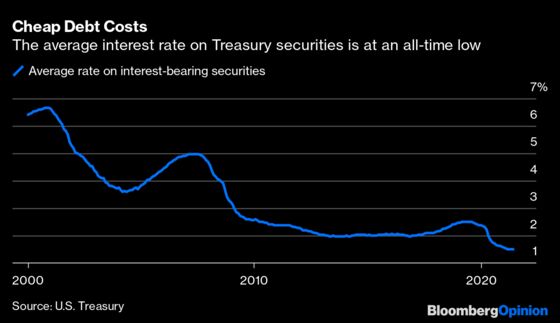

While the Fed’s dual mandate concentrates on maximum employment and stable prices, there’s little doubt that monetary policy also plays a pivotal role in allowing the U.S. government to run persistent budget deficits. The Treasury market is now $21.4 trillion in size, compared with just $2.9 trillion two decades ago. Yet you would be hard-pressed to find an investor who’s concerned about the ballooning national debt because the average yield the Treasury pays on its interest-bearing securities has never been lower and real inflation-adjusted yields remain deeply negative.

In a Bank for International Settlements working paper released last month, Ricardo Reis, a professor at the London School of Economics, laid out the implications of real interest rates (r) that are persistently lower than an economy’s growth rate (g), which in turn is below the marginal product of capital (m). That defines the U.S. situation. His top-line conclusion: “The government can run a deficit forever.”

The first three months of 2021 raised doubts about this kind of equilibrium lasting in the U.S. when the Fed was staying deliberately behind the inflation curve while elected officials were piling on additional fiscal stimulus. The benchmark 10-year Treasury yield jumped to 1.74% on March 31 from 0.91% at the start of the year in what was the worst quarter for U.S. debt since 1980. The 10-year real yield reached -0.54% in March, up from -1.12% in January. While those levels are still low by any historical measure, the trajectory seemed clear, and bond vigilantes appeared in control. As Reis put it: “If net spending is too high, the price of the debt will be zero, as the private sector refuses to hold this Ponzi scheme.”

Yet the 10-year yield has tumbled back below 1.5%, with the real yield at -0.87%. Using Reis’s words, the latest move shows that the “bubble premium” for U.S. debt remains firmly in place. It supports Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s view that President Joe Biden should push forward with his $4 trillion spending plans even if they lead to inflation that lasts into 2022. She added that Fed officials have the tools to deal with any lasting increase in price pressures.

The idea that the Fed will step in if necessary is crucial, because Reis’s research found that the idea of “inflating the debt” doesn’t really work because investors will demand a higher premium to hold government debt. That, in turn, constrains spending and ends up being a self-defeating proposition:

“To loosen the debt burden on the fiscal authority, the best action for monetary policy in this economy is to stabilize inflation as much as possible. This has a footprint on the government’s budget, because it permanently lowers the inflation risk premia that must be paid on the debt, creating fiscal capacity. Price stability generates fiscal resources, while a switch to monetary instability can trigger a rise r and cause a sovereign debt crisis.”

To be clear, there’s no reason to expect that any sort of debt crisis in the U.S. or other large developed economies is in the offing. And academic work can tend to ignore some of the structural forces that keep Treasury yields in check: demographics creating an insatiable demand for fixed income, foreign investors taking advantage of higher currency-hedged yields, and regulations that encourage banks to hold more U.S. government debt, to name a few.

Still, Reis’s report serves as a useful reminder that for all the talk about inflation and interest rates being too low for too long, that environment has also allowed for unprecedented government deficits and monetary-policy actions with relatively little consequence. It’s why Yellen used the term “slightly” in her comments last weekend. “If we ended up with a slightly higher interest rate environment it would actually be a plus for society’s point of view and the Fed’s point of view,” she told Bloomberg News’s Saleha Mohsin.

It’s true that the central bank would like to get away from the zero lower bound. But the fiscal reality suggests it can’t stray too far from it without risking the delicate equilibrium. For a sense of where the market starts to buckle, consider that 10-year real yields peaked at 1.17% in late 2018, higher than any point over the past decade. Yields collapsed the following year as U.S. growth slowed and the Fed cut interest rates. The experience so far this year suggests 2.5% is something of a soft cap on the nominal long-bond yield.

With Treasury yields sliding yet again, the Fed probably has enough cover to move toward talking about tapering its bond purchases so it’s in a better position to react later this year if the burst in inflation turns out to be not-so-transitory. Chair Jerome Powell has to walk a fine line between providing ample accommodation and proving that the central bank still has a handle on price growth and interest rates. Bond traders seem to believe in him and his colleagues for now — giving America the green light for deficits forever.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.