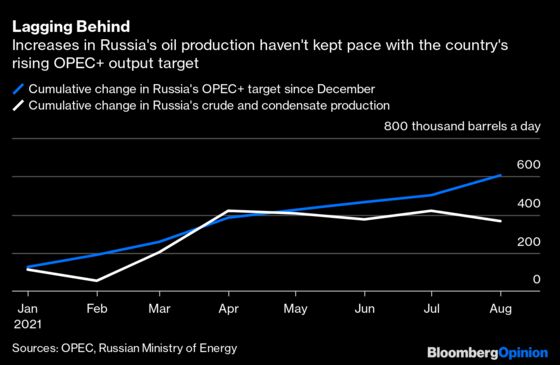

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Russia is struggling to boost its oil production, even as its allowance under the latest OPEC+ agreement is rising. At least that’s what the current data show. If it’s true, we ought to be worried.

The country is the largest of the allies that joined with the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries last year to agree to a record cut in oil production as Covid-19 slashed fuel demand. Now, as consumption recovers and the producer group is steadily restoring its curtailed supply, Russia is lagging behind.

Its production has flat-lined since April, while the amount it is allowed to pump under the deal has increased by 200,000 barrels a day. And that target is set to continue increasing at a rate of 105,000 barrels a day each month for the next year.

Maybe Russia has found a new sense of responsibility to pump closer to its OPEC+ target level, having been the group’s biggest over-producer in volume terms for much of 2020. But I doubt it. That would require the country to admit, at least privately, to past transgressions.

Alongside Saudi Arabia, Russia was given a baseline production figure — the level from which its output cuts are measured — of 11 million barrels a day, which will rise to 11.5 million barrels in April 2022. But, unlike the Persian Gulf kingdom, the Russian oil industry has never produced anywhere near that amount and almost certainly can’t do so now.

Part of the uncertainty over Russian production lies in definitions. The OPEC+ deal applies only to crude and excludes condensates — a light form of oil extracted from gas fields. Official Russian production numbers, published by the Ministry of Energy, combine the two and, as the world’s biggest natural gas producer, the condensate portion is significant. It probably amounts to about 800,000 barrels a day, or 8% of Russia’s total oil production (reported by ministry at 10.43 million barrels a day in August), but it likely varies seasonally with gas production.

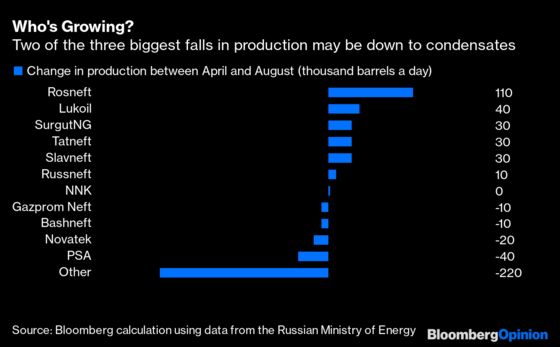

An important question mark is which of the two types of oil is falling. We don’t know, for example, if the stagnation in the country’s overall production is the result of a drop in condensates, which could mask an increase in crude. But if we look in more detail at individual companies’ production, there is some indication that condensates are underperforming.

Russia’s biggest crude producer, Rosneft Oil Co. PJSC, increased its production by 110,000 barrels a day, or 3%, between April and August. Lukoil PJSC and Surgutneftegas PJSC boosted output by similar percentages.

Among those whose output fell, Gazprom Neft PJSC is carrying out maintenance work at its offshore Prirazlomnoye field in the Arctic. The dip in Novatek PJSC’s production is in line with previous seasonal patterns, while one of the three projects being undertaken under production sharing agreements has also been undergoing planned maintenance.

That leaves the Other category in the chart above — a collection of small oil producers and one very large gas company, Gazprom PJSC — which has seen the biggest drop in production since April. Russia’s Ministry of Energy ceased publishing separate monthly oil production numbers for Gazprom in 2015, lumping the company into the Other category, where it then accounted for more than one-fifth of production.

It may be that lower condensate production by Gazprom has driven the slump in production by the Other group of companies. If so, the apparent stagnation in crude production since April may be illusory.

We ought to get an answer very soon. The company’s gas production should be ramping up ahead of winter as it seeks to put record volumes into domestic storage tanks. Condensate output should rise in tandem.

Russia’s oil production will be closely watched over the coming months and continued stagnation will raise concerns that the wider OPEC+ group can’t raise production by nearly as much as its future output targets suggest. That may be good news in the first half of next year (see last week’s column), as the group may need to trim supply anyway, but any relief will be temporary.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Julian Lee is an oil strategist for Bloomberg. Previously he worked as a senior analyst at the Centre for Global Energy Studies.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.