Why Covid Saw Fewer Fender-Benders But More Traffic Deaths

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- During the first wave of the Covid pandemic, something disturbing occurred on the empty roads of Virginia. Estimates made in the spring of 2020 found 45% fewer collisions had occurred in the preceding year, if compared with the pre-Covid year ending in the spring of 2019. Yet more drivers had died in crashes. Bizarrely, fatal crashes involving extreme speeding and non-use of seat belts had increased by 78%. The roads had become less congested but also deadlier.

Across the U.S., what happened in Virginia happened in many other states as well. Why? Perhaps it was pandemic rage, a direct consequence of the psychological burden of the pandemic? Or did anti-Covid measures keep the more cautious part of the population off the roads, leaving a riskier group of remaining drivers, with a predictable outcome? Or maybe it had nothing to do with Covid at all — maybe it was a continuation of a pre-existing trend. After all, road fatalities have been climbing in the U.S. for a decade, in part due to bigger vehicles and in part because more drivers are drinking, using drugs, or looking at their phones.

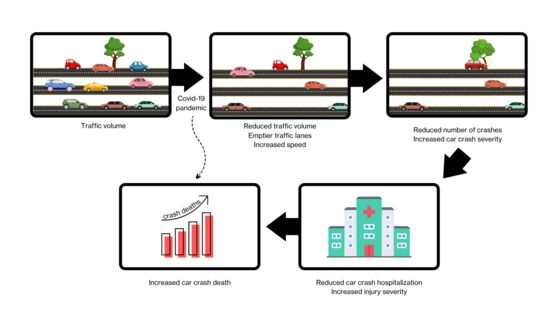

All of these factors probably played some role, yet another, simpler factor may be even more important. A meta-analysis looking at dozens of studies of pandemic collisions worldwide finds, in general, a pronounced reduction of both traffic and overall road deaths during the pandemic in most countries. Yet along with this reduction came a spike in the fraction of deadly crashes linked to factors such as extreme speeding. The most frequently cited cause: less-congested roadways, which allow faster driving — something traffic experts call the "speed effect."

Perhaps pandemic psychology also played some role. But quite ordinary psychology linked to the lure of open roadways seems to have had a significant effect.

Research published in the World Journal of Emergency Surgery surveyed well over 100 studies of road collisions and their consequences during the pandemic. Summarizing the findings of such a sprawling study isn't easy, but one principal theme is that traffic patterns differed widely by country. For example, traffic densities fell between 25% and 75% in different European countries, compared with 40% on average in the U.S. Total traffic deaths dropped significantly in almost all nations, with exceptions including Denmark, Sweden, the Netherlands and the U.S., where overall traffic deaths rose slightly.

But there were commonalities. Most strikingly, across all nations, the Covid period showed a significant shift toward more severe and deadly crashes involving high speeds. In Spain, the fraction of deadly crashes increased five-fold over the first year of Covid. Similarly, collisions involving extreme speeds became three times more likely in the U.K. In the U.S., numbers increased 65% in Boston and 167% in New York. They nearly quadrupled in Chicago.

Many of the studies also suggested a fairly simple cause for this outcome: less road congestion. For example, one detailed study in California based on extensive crash, speed and traffic flow data found that highway travel and the number of collisions fell substantially during the pandemic, but that the frequency of severe collisions increased due to lower traffic congestion and higher driving speeds. The lead author of this study, economist Jonathan Hughes of the University of Colorado, a specialist in traffic policy, attributes the increase to the “speed effect,” a well-known traffic phenomenon.

"The ‘speed effect’ is the increase in traffic fatalities due to higher average traffic speeds," he told me by email. "On many California highways, speed is typically limited by congestion not by speed limits or driver preferences. With many drivers staying home during the early Covid-19 period, the decrease in traffic allowed remaining drivers to drive faster, meaning that the crashes that did happen were more severe because they happened at higher speeds."

Significantly, Hughes and colleagues found that the increase in deaths from extreme speeds was most pronounced in California counties with higher levels of congestion prior to the pandemic, suggesting this is where reduced congestion let drivers increase their speeds the most.

Nonetheless, Hughes suggests there's some sense to the idea that the pandemic could have changed the behavior of the riskier drivers on the road, although he says the story is more complex than most people think. If traffic is stop and go, the danger posed by a risky driver is mitigated by congestion from other cars on the road. Reduce congestion and the risky drivers are no longer constrained, and can potentially drive more dangerously. So the speed effect could involve some combination of less congestion allowing everyone to drive faster, and also removing some constraints on the riskier drivers.

"We find some evidence," he says, "of increases in the proportion of crashes involving drivers typically viewed as more risky. The proportion of crashes involving male drivers increased from 61% in the months before Covid to approximately 67% during the initial Covid period. However, the main effect on fatalities seems to come from higher average speeds for all drivers."

One of the paradoxes of this "speed effect" is that it has implications going beyond the pandemic. If the shift toward deadlier crashes was less about the pandemic, and more about just the reduction in traffic congestion, then the same result would be expected from any traffic measures that reduce congestion, including building new roads. Any policy that reduces congestion might increase speeds and also crash severity. So if you’re frustrated by sitting in rush-hour traffic once again, consider the upside: at least no one’s driving too fast.

More from Bloomberg Opinion:

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mark Buchanan, a physicist and science writer, is the author of the book "Forecast: What Physics, Meteorology and the Natural Sciences Can Teach Us About Economics."

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.