Fed Trapped by a Covid Exemption for Bank Leverage

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Credit Suisse says it’s no “magic bullet.” Bank of America insists it’s a “red herring.”

And yet all it takes to whip bond traders into a frenzy is the mention of a three-letter acronym — SLR.

That stands for supplementary leverage ratio, a requirement stemming from the Basel III accord that says U.S. banks must maintain a minimum level of capital against their assets without factoring in risk levels. As a way to push banks to help the country get through the Covid-19 pandemic, regulators allowed them to temporarily exclude U.S. Treasuries and deposits at the Federal Reserve from the SLR denominator because they are the closest thing to risk-free assets. In addition to helping banks continue to take deposits and lend during the health crisis, it also served to ensure they would help backstop the unprecedented fiscal and monetary policy support that flooded the financial system with cash.

This emergency move is set to expire on March 31 — and the Fed has been unusually silent about the SLR’s fate ahead of its policy decision next week. Jelena McWilliams, chair of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, said last week that she doesn’t see the need to extend the interim rule at the depository institution level, according to Politico. Because the FDIC, Fed and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency collectively approved the measure last year, markets have taken McWilliams’s stance as effectively ruling out a widespread extension. Even though she said the most important question rests with the Fed, which regulates the parent holding companies, that’s not quite right either, Mark Cabana, head of U.S. rates strategy at Bank of America, told me in an interview, because holdings of Treasuries went up significantly at depositories over the past year, not dealers.

It makes sense why Cabana calls the SLR debate a “red herring.” It’s inherently complicated and requires a deep understanding of the private banking system and how the Fed’s balance sheet works — beyond the “money printer go brrr” meme. When digging in, it becomes clear that the Fed has no easy solutions to maintain a healthy banking system and Treasury market.

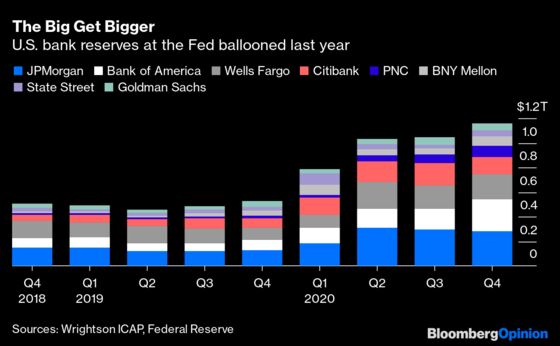

First, it’s important to understand the mechanics behind the Fed’s bond-buying program. When it purchases Treasuries from a money manager, those securities become an asset on the central bank’s balance sheet. The seller will deposit the cash it received at a bank, which, left as reserves at the Fed, is an asset for that bank and a liability for the Fed. In other words, quantitative easing boosts the asset levels of U.S. banks, which, in turn, means they need to hold more capital.

There’s nothing wrong with the Fed, as a regulator, requiring that banks maintain adequate capital to avoid another financial crisis. But it’s a hard sell when the Fed, as the nation’s monetary policy authority, is forcibly increasing the asset base. This kind of internal struggle explains why the SLR exemption was put in place; it’s anyone’s guess what might have happened without it as the Fed expanded its balance sheet by almost $3 trillion in three months.

So, what to do? At first glance, the easy answer seems to be to just extend the SLR exemptions for Treasuries and reserves to avoid disrupting this market plumbing. By some measures, this break allowed banks to expand their balance sheets by as much as $600 billion — why mess with that? However, the Fed created its own political problem by loosening its restrictions on banks’ cash distributions, which had been put in place after the pandemic. Banks are now buying back stock and distributing capital to shareholders, or, in SLR terms, willfully reducing their numerator. It stands to reason, then, that they could afford to have the denominator return to its usual form.

This is the argument from Democratic Senators Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Sherrod Brown of Ohio. In a letter to regulators last month, they argued “to the extent there are concerns about banks’ ability to accept customer deposits and absorb reserves due to leverage requirements, regulators should suspend bank capital distributions. Banks could fund their balance sheet growth in part with the capital they are currently sending to shareholders and executives.”

Another problem with extending the SLR exemption is that it truly benefits only a few large banks, as Zoltan Pozsar, a strategist at Credit Suisse, noted during a recent Bloomberg “Odd Lots” podcast. Not only is such favoritism politically fraught, but it runs the risk of falling short of what’s necessary to absorb the amount of cash hitting the financial system. The SLR exemption is talked about as a “magic bullet,” he said, but that’s not really the case.

“Maybe only reserves should exempted permanently, but not Treasuries — that would be more in line with the global standard,” Pozsar said, floating an idea that has been bandied about by strategists. But that creates new issues in short-term rates markets. Specifically, when overnight repo rates climb above the Fed’s interest rate on excess reserves, or IOER, banks have a natural incentive to use their cash to step into the repo market and capture a higher return.

That behind-the-scenes arbitrage might not happen if only reserves were exempt from SLR calculations because Treasuries typically serve as collateral for repo transactions. In such a circumstance, “there’s regulatory benefit to holding cash,” Cabana said, and banks would be less likely to serve as the “repo police.” It has been less than two years since the repo meltdown of September 2019, which JPMorgan Chase & Co. Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon blamed in part on regulations, and the Fed isn’t eager for a repeat performance.

Dimon, for his part, raised the specter of having to turn away deposits at some point without SLR relief during the bank’s earnings call in January, which would obviously be quite a drastic business decision. In response to the same question, Chief Financial Officer Jennifer Piepszak described the whole situation rather bluntly:

“Obviously it is an issue for us in the near to medium term, should we not get the extension and it’s one that's important for people to understand. But we bring it up more so, because it’s another example of where lack of coherence around this, that these rules can have an impact, not just on JPMorgan. So we don’t bring it up, just because of the impact on JPMorgan. We bring it up because it is perhaps one of the better examples of the need for recalibration. You have to have the right incentives in the system for it to work through time. And we’re just seeing that, that’s not the case.”

These are the leaders of the largest U.S. bank saying the Fed has a serious problem. To Cabana, the recent angst over the SLR extension has less to do with the actual mechanics and is more about the rapid increase in Treasury yields over the past two months, which happened to coincide with the expiring exemption. “What all of this indicates to me is there’s heightened sensitivity over where Treasury demand is going to come from and whether Treasury rates can remain here,” he said. “Because there’s a lot of debt out there, and it’s only going to keep growing.” The U.S. is auctioning $38 billion of 10-year notes on Wednesday and $24 billion of 30-year bonds on Thursday.

It’s rare for the Fed, arguably the most powerful financial institution in the world, to look as if it’s trapped. Not granting an SLR extension, especially with traders so focused on it, runs the risk of pushing up Treasury yields, which at a certain point could hamstring the recovery and jeopardize its goals. Extending the exemptions is bad optically, will draw political opposition and might not even resolve underlying issues with the financial plumbing and the growing size of the Treasury market. It’s not clear there’s better middle ground, though Bank of America’s suggestion to allow reserves and Treasuries accumulated during the pandemic to be exempted could potentially do the least damage.

Whatever the Fed decides to do, it won’t be a panacea and it won’t be a disaster. But it’ll likely be messy. For central bankers who are used to being in control, that’s equivalent to a no-win situation.

I'd encourage you to listen to the podcast in full, but Pozsar goes into further detail explaining why even JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Citigroup Inc. don't stand to gain much from an SLR extension, leaving just Bank of America and PNC Financial Services Group as the main beneficiaries.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.