(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s been a turbulent couple of years for U.S. distillers. Starting in June 2018 they became collateral damage in then-President Donald Trump’s trade wars, with the European Union levying a 25% tariff on U.S.-made whiskey in retaliation for new U.S. duties on imported steel and aluminum. Tariffs on other alcoholic beverages followed from both the U.S. and EU, mostly as part of a battle over aircraft-manufacturing subsidies. “We’ve been a casualty of a very challenging trade war,” the chief executive officer of Brown-Forman Corp., the Louisville, Kentucky-based distiller of Jack Daniels, Woodford Reserve and Old Forester whiskeys, told Bloomberg News recently.

Not to mention a pandemic that shut down bars around the world. Must have been a really tough stretch for Brown-Forman, right? Well ...

Brown-Forman is the best publicly traded proxy available for the American distilled spirits industry, given that it gets almost 80% of its revenue from whiskey, most of it U.S.-made (outside the country it makes three Scotch whiskys, an Irish whiskey and non-whiskey drinks including Herradura tequila, Finlandia vodka and Chambord liqueur), and U.S. consumers account for a little over half its sales. Most U.S.-distilled spirits are either small cogs in global drinks machines such as Suntory Holdings Ltd. (Jim Beam, Maker’s Mark), Diageo Plc (Bulleit) and Davide Campari-Milano NV (Wild Turkey) or made by privately held companies, notably Heaven Hill Brands of Bardstown, Kentucky (Evan Williams, Rittenhouse Straight Rye), and Sazerac Co. of New Orleans (Buffalo Trace, Blanton’s, Pappy Van Winkle.)

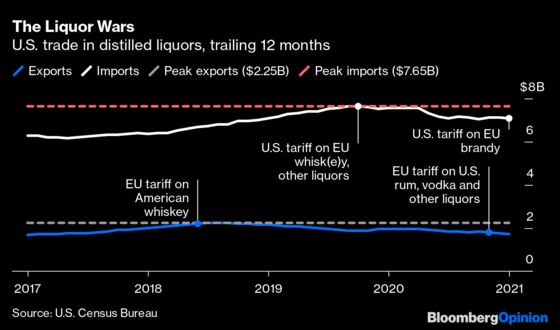

It’s not as if the trade wars haven’t hurt. U.S. exports of distilled spirits are down $523 million, or 23%, from their peak in September 2018, according to the Census Bureau, and imports are down $569 million, or 7%, from their peak a year after that. Brown-Forman accounts for about two-thirds of U.S. whiskey exports into the EU and U.K., CEO Lawson E. Whiting said in the company’s March 3 earnings conference call, and thus has borne the bulk of the tariff burden.

The pandemic has exacted its toll too. Sales of company flagship Jack Daniels Tennessee Whiskey, a standby of bartenders in the U.S. and many other parts of the world, are still down “high-single digits” versus a year earlier, said Chief Financial Officer Jane Morreau.

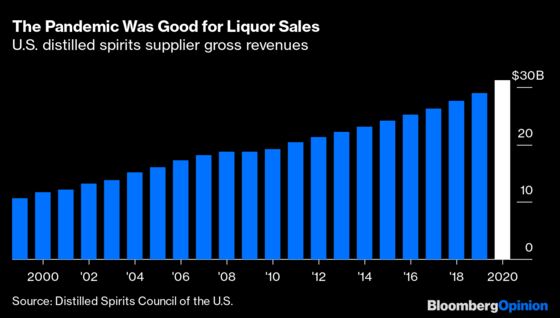

But overall U.S. sales were up 4.1% at Brown-Forman for the four quarters ending this Jan. 31, despite its divestment last summer of several lower-end whiskey brands. For the U.S. liquor industry as a whole, supplier revenues were up 7.7% in 2020, according to the Distilled Spirits Council of the U.S., the biggest percentage increase in 18 years and the biggest dollar increase on record. The pandemic apparently drove a lot of people to drink the hard stuff.

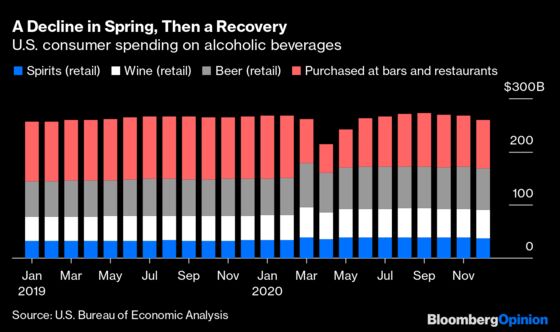

The monthly consumer spending data from the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Economic Analysis makes a little clearer how exactly this came about. Restaurant and bar closures did bring alcoholic beverage sales down in the spring, but in summer a new normal was established in which a partial recovery of beverage sales at bars and restaurants (helped in part by states changing liquor laws to allow them to sell drinks to go) combined with sustained higher retail sales to drive overall sales higher — although the lack of holiday parties and resurgence of the pandemic did tamp things down a bit again in December.

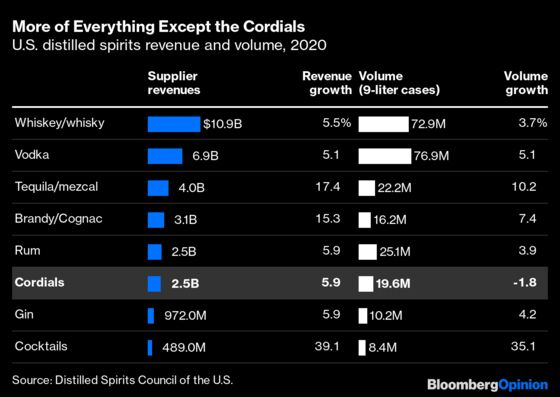

There was also a shift in which kinds of drinks were selling. Liquor sales rose faster than those of beer and wine, while within the spirits category tequila and brandy saw bigger gains than whiskey and vodka. The volume of cordials (liqueurs, amari and such) actually went down as bars bought fewer to mix into cocktails, although revenue still went up as retail customers opted for higher-end products than bars tend to do. The fastest-growing category of all was pre-mixed cocktails. At Brown-Forman, U.S. sales of Jack Daniel’s Country Cocktails (Black Jack Cola, Lynchburg Lemonade, Downhome Punch, etc.) more than doubled over the past year.

So what’s next for the purveyors of whiskey, vodka and other hard drinks? With Trump out of the White House, their tariff woes have already begun to subside. Earlier this month, the EU and U.S. announced a cease fire in their battles over Airbus SE and Boeing Co., and suspended the related tariffs on food and alcoholic beverages. The standoff over steel and the accompanying tariffs on U.S. whiskey continues, but prospects for resolution are clearly better under a Joe Biden presidency than they were before.

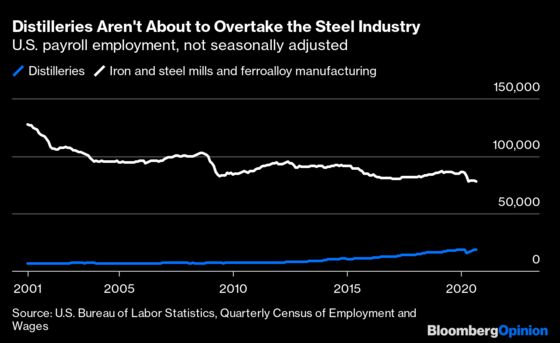

Given that the U.S. imports a lot more distilled spirits than it exports, one might wonder if it’s really in the interest of distillers here for all these trade disputes to be resolved. But the renaissance of American bourbon and rye in recent years helped drive a 75% increase in U.S. spirits exports over the decade ending in 2018, while imports were up 49%. U.S. distilleries have also seen employment rise 141% over the past decade, although when I dug into the jobs data to see whether they were coming close to rivaling the steel industry that landed them in this tariff trouble, the answer was no, not really. (Also, average annual pay was $90,627 at steelmakers in 2019, versus $63,965 at distilleries.)

Still, distilling is a growth industry in the U.S., and one with nice undertones of craftsmanship and local color. I purchase its products, have toured several of its manufacturing facilities in Kentucky and want it to thrive. That said, I also drank way too much last year and have cut back sharply on my consumption since. I don’t think I’m the only one, either. After that historic increase in U.S. liquor sales last year, this may be the year of the hangover.

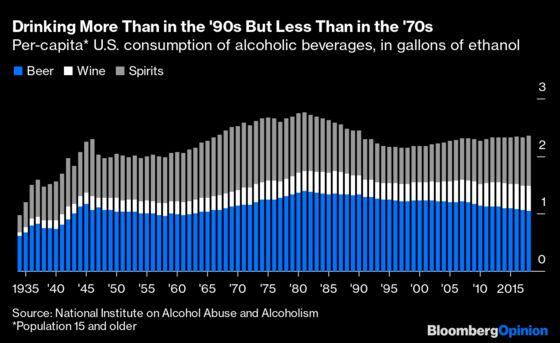

The long-run picture for alcohol consumption in the U.S. is that it reached its highest per-capita level in more than a century in 1981, then declined in the 1980s and 1990s as hard liquor fell quickly out of fashion and beer drinking more gradually subsided. Since the turn of the millennium beer consumption has kept falling, but the whiskey and cocktails revival and the continued growth of wine drinking has led to a modest increase in overall alcohol consumption.

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Prevention has intermittent consumption estimates going back to 1850, and they show per-capita drinking nearing but not surpassing the 1981 peak in the early 1900s and in 1860. In those days men were likely responsible for a higher share of consumption than today, so their per-capita intake was relatively higher. In the mid-1800s the intake was also almost 90% spirits, and other estimates put per-capita consumption at a staggering 7.1 gallons of ethanol in 1830 and 5.8 in 1790, presumably almost entirely spirits. So we definitely could drink a lot more liquor than we do now.

Should we, though? After a sharp decline in the 1980s and 1990s, the death rate from cirrhosis of the liver began rising again in the 2000s. Annual deaths from all the underlying causes I could find with the word “alcohol” in them in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s database doubled from 19,180 in 1999 to 38,589 in 2019, with the rate per 100,000 population going from 6.9 to 11.8.

Most of these deaths aren’t people having a few sips of Woodford Reserve of an evening, and the high-end distilleries that have driven the whiskey revival (“high end premium” and “super premium” brands accounted for 81% of the growth in American whiskey revenue from 2002 to 2020) probably still have room to grow. But I do wonder if, after a pandemic binge, this country might be due for another of its periodic reckonings about alcohol.

There's also Constellation Brands Inc., which is U.S.-based and publicly traded, but spirits such as High West Whiskey remain a pretty tiny part of its beer-and-wine-dominated business.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.