(Bloomberg Opinion) -- A series of dispatches from America in the age of Covid-19.

Word got out here that nasal swabs were the only thing standing between Northern California and a lot of coronavirus testing, and people with a talent for figuring out things began to figure things out. Marc Benioff, the chief executive of Salesforce, flew a plane full of medical supplies from China to the University of California at San Francisco Medical Center, and some functional though less-than-ideal nasal swabs were happily among them.

Chris Kawaja, the owner of a chemical company with dealings in China, found another off-brand Chinese nasal swab supplier, and messaged them. “I said, ‘Hey, do you have these things?’” says Kawaja. “And this woman came right back and said, ‘Yeah, I have 250,000.’” These swabs were the real deal, but before Kawaja could nab them the Chinese woman sent another message to say, “Some guy in Houston just took 200,000 of them.” Kawaja charged the rest to his credit card — at 70 cents a pop, triple the old market price — and had them shipped to San Francisco in small batches, to evade the notice of Chinese customs officials. “It did occur to me: Why did I need to find this stuff?” says Kawaja. “Why did some random dude in Marin need to read some random newspaper article about how Joe DeRisi needed swabs, and go and find the swabs?”

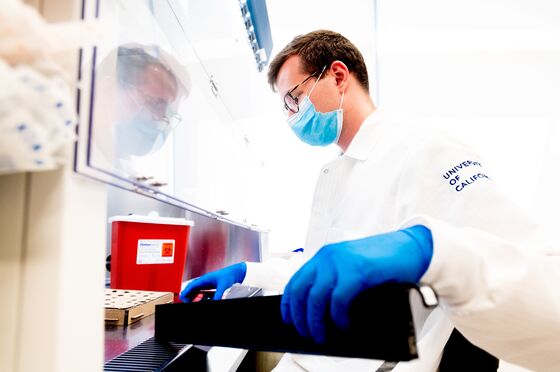

DeRisi is an infectious disease specialist and co-president of the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub in San Francisco. I’ve been following his work and have already written about how, in the first three weeks of March, he used a volunteer labor force of 200 graduate students to build the fastest big coronavirus testing lab in the country from scratch — only to find that an absence of nasal swabs left him little to test. The swabs are no longer a problem, and the Biohub suddenly has a magic flashlight, with the power to see both where the virus hides and how it moves.

There’s now the question of where to point it. Not, DeRisi thought, at people turning up at hospitals with coughs and fevers: Their tests didn’t tell you much that you didn’t already know about where the disease might next travel. Random sampling of some community, obvious as it sounds, might not be the best idea either. “Just testing anyone may not be the right strategy,” says DeRisi. “You want to get the most bang for your buck. You want to go out and find the virus, so you can isolate it. We’ve been playing defense. Now we can start playing offense.”

The first swabs the Biohub received that hinted at any sort of strategy came, oddly enough, from the weird and remote beach town of Bolinas, just north of San Francisco. The bookstore in Bolinas has no cash register but a sign telling customers to take whatever book they want and to stick however much they think it is worth into a collection box. The whole town is like that. A local entrepreneur named Cyrus Harmon, frustrated by his inability to get himself and his family tested, had gotten in touch with UCSF researchers and offered to pay to test all the town’s 1,400 residents. He’d read the story of Vo, a village in Northern Italy, that has escaped the worst of the pandemic by testing all its residents and isolating the infected. It took Harmon and a venture capitalist also living in Bolinas three weeks to do for 1,400 California communists what the U.S. government and the big lab testing companies say they still can’t do for 100 U.S. senators: Test everyone, fast.

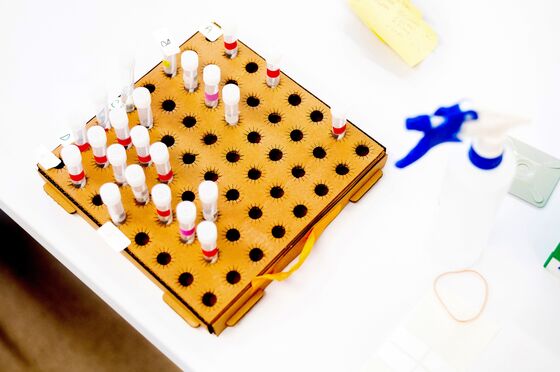

There were some glitches. The first batch of Bolinas samples arrived at the Biohub in a garbage bag. “Ten percent of the tubes had leaked,” says DeRisi. “Because they’d used shitty swabs that didn’t fit inside the tubes.” Even then it took DeRisi’s graduate students less than two days to hand the entire town of Bolinas its results: No one had the virus.

Bolinas had never struck DeRisi, or anyone else, as the best place to go virus hunting. Rich people with lots of space and a preference for isolation were not the most likely hosts. But the idea of testing everyone in some town or neighborhood struck DeRisi as a good one, maybe even a great one. You just needed to go looking in places the virus was more likely to be hiding. One of them happened to be right around the corner.

*****

Last Sunday, my college sophomore daughter and I marched up and down every street in four square blocks in San Francisco’s Mission District. These four square blocks constituted just another tract in the U.S. Census but were of special interest to a virus hunter: Less a typical American community than a place with aspects of many different American communities. It was as if someone had thrown the pieces to seven different jigsaw puzzles into one box. It has charming Victorian houses, less charming housing developments, and brutalist, densely packed apartment buildings. It has people living on the streets. It has upper middle class and really poor people. It has teleworkers and construction workers. It has four churches, a street of retail shops and a park. It holds a big working-class Latino population but also, like chips in a cookie, hipsters and tech bros — though when I told my daughter this she said, “Hipsters would never live anywhere near tech bros.”

Well, now they did and they had something else in common: They’d all been tested for the coronavirus. Or, at any rate, most of them. Over the previous week a team of 450 volunteers, supervised by a UCSF medical researcher named Diane Havlir, had drawn blood and swabbed the noses and throats of several thousand Mission residents, then sent the samples to DeRisi. In three days they’d taken nearly a third of the test samples collected in the greater San Francisco area since the pandemic’s start.

Havlir, an AIDS researcher, had earned the trust of the locals over many years of working with them to control that disease. Walking around you got a sense of the wariness she’d had to overcome. The lower floor windows of most every building had bars, like jail cells. Signs everywhere told strangers to keep out, and murals and graffiti had unkind words for ICE. Men without masks walked dogs without collars and both eyed you a bit as you passed them on the street. Even the sweet aspects of street life felt vaguely threatening: children, clearly from different households, playing together in the street; a card game in the park; seven men without masks, seated along a wall beside the park, too close to each other. What once seemed commonplace now left you wondering if you should call the department of public health.

The researchers announced the initial results of the Mission study on Monday. Just the positives and the negatives, not what is likely to be the more revealing data from the genetic analysis. But even those crude results paint a picture of how the virus might be getting around — one that is clearer than just about any that the city, or for that matter, the country has had until now. “The departments of public health are operating in a permanent mindset of scarcity,” says DeRisi. “They aren’t doing any of this sort of sampling.” Which is a great pity as it is amazing what it can reveal. Slightly more than 2% of the people tested in the four square blocks currently have the coronavirus, for instance. Only 1 in 10 of them has a fever and most have no symptoms at all — which is to say that, absent the testing, they’d probably still be walking around and infecting people without knowing it.

There was more. Of the 981 white people tested, zero have the virus. Latinos are only 44% of the study but 95% of the positives. Men are a bit more than half of the sample but 75% of the positives. Just over half of the people tested say they’re unable to work from home — but that group registers 90% positive. Being in a crowded house appears to be a problem: nearly 30% of the positives come from households of more than five people, though those households make up only 15% of the population. Being poor is a bigger problem: people earning less than $50,000 a year are 89% of the positives, though only 39% of the group studied. Only a quarter of the people with the virus have a primary care doctor. Six of the people with the virus still haven’t been located by the researchers, and informed that they’re ill.

The data you get when you go out and test people without symptoms is different from the data you get when you only test those who show up in a hospital. You learn some of the same things — for instance that the people most susceptible to the virus, and maybe also most likely to spread it, are the people who can’t afford to isolate themselves. But the outside data might also tell us a whole bunch of stuff that the hospital data won’t.

Joe DeRisi and his volunteer army of grad students are now busy in their labs studying the genetic markings of the viruses they’ve found. And asking the questions that need to be answered, to reopen the society without lots more sickness and death. For example: How’s this virus moving through society? “There are all kinds of rumors,” says DeRisi. “Are kids the hidden vector? Or can you get it from a handrail? Those guys sitting along the wall beside the park — are they the problem? Or is it the guys playing cards in the park?” By studying the genomes of the samples, he may be able to answer those questions, and others. He’ll be able to see, for instance, if parents are infecting their children or if it’s the children infecting their parents. “There’s so much we don’t know,” says DeRisi. “We honestly don’t know what we’re going to find. That’s what’s cool about it. It’s science!”

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Michael Lewis is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. His books include “Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt,” “Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game,” “Liar’s Poker” and “The Fifth Risk.” He also has a podcast called “Against the Rules.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.