Nursing Homes Are Only as Safe as Their Communities

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- About 2.2 million Americans, or a little under 0.7% of the country’s population, live in nursing homes and other residential-care facilities for the elderly. Residents of these facilities, meanwhile, have by some estimates accounted for more than 40% of U.S. deaths from Covid-19.

This “astounding share of deaths,” as conservative health-policy expert Avik Roy described it last month, has raised lots of questions about whether a different approach to managing the disease in the U.S. might have been able to spare the lives of nursing-home residents while allowing for fewer restrictions on everyone else. I don’t exactly have answers to those questions, and in truth I don’t think anyone does yet. I have collected some numbers, though, that may help put the issue in context.

First, there’s nothing particularly surprising about nursing homes and their ilk accounting for a much larger share of Covid-19 deaths than they do of the population. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention keeps track of deaths by location, and from 2014 through 2018 19.5% of U.S. deaths from all causes and 20.9% of deaths from internal causes occurred in nursing homes and other long-term-care facilities. Since late January of this year, 24.1% of the deaths from Covid-19 for which the CDC has data on place of death have occurred there.

This is lower than the 40%-plus cited above because it does not count nursing home residents who die in hospitals. A lot of nursing home residents die in hospitals in normal years, with a large-scale study from the 2000s putting the share at about 20%, but with Covid-19 the percentage seems to be at least twice that. So yes, nursing homes do seem to have been inordinately affected. But they have also suffered heavily during past outbreaks of influenza and even the common cold, and though their share of U.S. Covid-19 fatalities is high it hasn’t really been “astounding,” or markedly different from that seen in other countries.

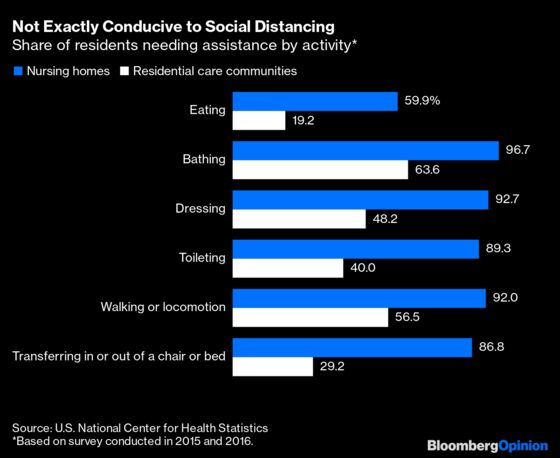

Nursing homes and their ilk are especially vulnerable to infectious diseases such as Covid-19 because their residents are frail elderly people with weak immune systems who spend a lot of time indoors, often in shared bedrooms, and generally cannot avoid coming in close contact with their caregivers. The numbers below are from a 2015-2016 survey by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics that is also the source of the most up-to-date estimates of nursing home and residential care community population:

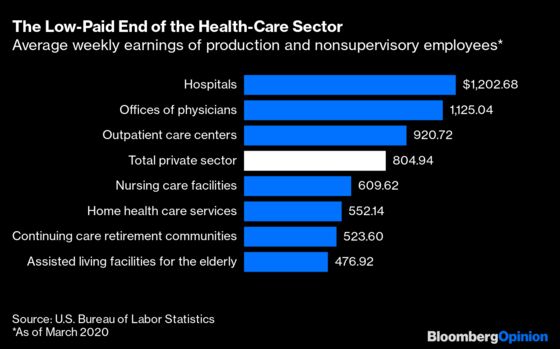

These caregivers, meanwhile, are among the lowest-paid workers in the health-care sector — or any sector, for that matter.

Because pay is so low, caregivers for the elderly often live in overcrowded conditions and work multiple jobs. They’re also less likely to have health insurance or access to paid sick leave than other health-care workers, and while the Families First Coronavirus Response Act passed by Congress in March addressed these issues somewhat, there were loopholes.

It shouldn’t be too surprising, then, that two recent studies of the characteristics of nursing homes hit hardest by Covid-19 found that the main things they had in common were (1) locations in communities with high incidence of the disease and (2) large size. Another study found that race of the residents was the best predictor, but that sadly kind of fits with (1). Keeping Covid out of nursing homes when it is spreading widely in places where employees live, shop and commute is very hard to do — and is hardest in larger facilities because more employees are going in and out. This was especially true early in the epidemic in the U.S. when testing for the disease was nearly nonexistent and personal protective equipment scarce, but it remains a challenge.

Media discussions of the nursing home toll have often focused on state policies. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo has come under huge amounts of fire for the state’s decision in March to require that nursing homes accept recovering coronavirus patients (who generally don’t seem to be contagious, but one never knows) and others suspected of having the disease. The policy, which has since been reversed, resulted in more than 4,500 such admissions in the state, according to the Associated Press. But while future studies may find that it worsened the state’s outbreak, at the moment it’s awfully hard to find evidence of such impact in the data.

That is, if New York’s policy led to lots more nursing home deaths from Covid-19, one would expect nursing homes’ share of deaths from the disease to be much higher in New York than in other states. Comparisons are harder than they should be, in part because New York has not released numbers on nursing home residents who died in hospitals. But in the CDC’s count of deaths by location, the share of Covid-19 deaths occurring at nursing homes and other care facilities in New York is 16.7%, below the 24.1% national average.

It’s an even lower 5.1% in Florida, where Governor Ron DeSantis banned most nursing homes from accepting Covid-19 patients (designating several Covid-only facilities instead). But the share of deaths that occur at nursing homes is perennially lower in Florida than in other states, seemingly in reflection of different policies and practices regarding hospices, which in Florida account for a much higher share of deaths than they do nationally and in New York a lower share. If you add together deaths from Covid-19 at nursing homes and hospices, they come to 17.8% of the total in Florida, 18.1% in New York and 26.4% nationally. Meanwhile, Florida’s estimate of Covid-19 deaths among nursing home residents regardless of place of death puts them at close to half the state total.

In other words, go figure! Florida has of course had far fewer deaths overall from the coronavirus than New York, but that may be because it implemented school closings, nonessential business closures and other social distancing measures before the disease had spread widely in the state while New York’s lockdown came too late, with differences in spring weather and urban density perhaps contributing as well. Now that the disease is spreading rapidly in Florida and continuing to ebb in New York, we’ll presumably learn more.

More testing and PPE availability, and perhaps smarter state policies, may allow nursing homes in Florida and other states now experiencing Covid-19 outbreaks to fend them off more successfully than those in New York and elsewhere in the Northeast did. But one also has to hope that testing, masks and other measures keep those outbreaks from getting quite as out of control as New York’s did. So far I’m not aware of any place that has successfully protected nursing homes amid major spread of the disease. In Sweden, where letting Covid-19 circulate among the young while protecting the elderly was part of the government’s original plan, nursing homes now account for about half of a death toll that is on a per-capita basis among the highest in the world.

There’s one other thing about U.S. nursing homes in particular that may cause problems as Covid-19 continues to spread. Medicare, the federal health insurance program for the elderly, does not pay for long-term care, and most nursing-home residents (61.8% in the 2015-2016 survey cited above) rely on Medicaid, the federal-state health insurance for those with limited resources, to pay their bills. (At other long-term-care facilities the clientele is wealthier and the Medicaid share 16.5%.) Medicaid reimbursements generally don’t cover the cost of care, so to make ends meet nursing homes also care for short-term patients recovering from hip replacements, heart attacks and the like whose costs are reimbursed by Medicare at much more generous rates.

By putting a temporary halt to elective surgeries, Covid-19 pretty much dried up that source of income. Medicare does pay the bills for recovering Covid patients, and despite the obvious complications some nursing homes are courting them and on occasion even evicting long-term residents to make room. Still, the overall nursing home population has fallen by an estimated 100,000 since the beginning of the year, and the industry’s trade group warns of a wave of bankruptcies and closures to come in the absence of more federal aid. Nursing homes aren’t really to blame for Covid-19’s high death toll, but it can sometimes seem like we’ve designed them to make it worse.

That is, I compared the numbers that hard-hit New Jersey reports on total deaths of nursing home residents to the CDC's tally of state deaths at nursing homes and came up with a 47% not-in-nursing-homes share, which is probably a little high because the CDC data are less timely than the state data.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.