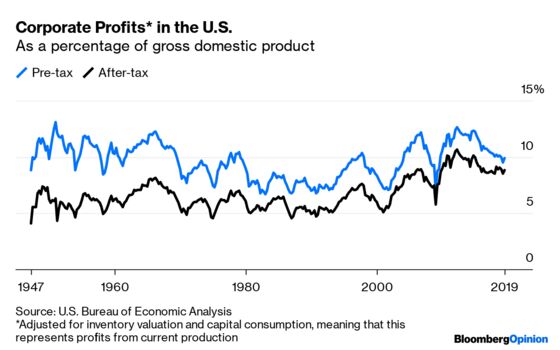

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Early in the current economic expansion, after-tax corporate profits were setting record after record as a share of gross domestic product. The share going to wages and salaries, meanwhile, was at an all-time low (going back to 1929). This inspired some understandable hand-wringing, and a growing body of economic research on what exactly had been causing this seeming income shift from labor to capital.

Since 2012, though, the corporate profit share in the U.S. has been mostly falling:

Corporate profits did rebound a bit in the second quarter, according to the preliminary estimate from the Bureau of Economic Analysis that was released last week along with the second estimate of second-quarter GDP. Also, the after-tax profit share isn’t down nearly as much as the pre-tax share, thanks to the sharp decline in the corporate income tax rate in 2018 brought on by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. But the overall profit trend, which became much more apparent after annual GDP revisions made in July, is remarkable — it’s “the longest late-cycle contraction in post-war history,” as Gregory Daco of Oxford Economics put it.

For most of the post-World War II era, sharp declines in corporate profits’ GDP share tended to coincide with, and sometimes presage, recessions. Declining profit margins caused corporations to cut back on investment and hiring, which caused slowdowns that compressed margins even more. (Or something like that.) The decline in profit as a share of GDP that began in late 1997 took three years to translate into a downturn, a sign that the connection between the two was weakening, perhaps because of globalization. But then the decline that began in late 2006 was followed pretty quickly by the Great Recession. Now we’re in year seven of such a contraction. What the heck is that supposed to mean?

One possibility is that we are finally headed for the cyclical downturn that the profits/GDP chart has been pointing to for years. But it could also be that, after rising through the cyclical ups and downs from below 8% of GDP in the 1980s to above 12% in 2006 and again in the early 2010s, the corporate profit share has peaked and is now on a long-run downtrend. Which maybe isn’t the greatest news for equity investors, but could mean a healthier, more balanced economy. After all, if the share of GDP going to corporate profits is going down, somebody else’s share has to be going up. And it looks like the growing slice of the pie is going to workers:

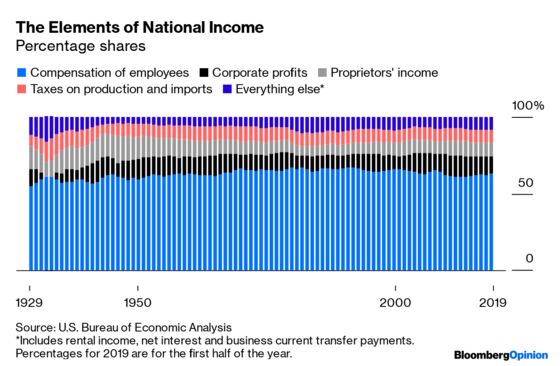

I’ve switched from dividing by GDP to dividing by national income because it is on the income side of the BEA’s National Income and Product Accounts that corporate profits are reported. Doing it this way makes more sense — among other things, profits earned overseas by American corporations are counted in national income and not GDP. But profits as a share of GDP seems to be the metric of choice for Wall Street economists, which is why I started with that.

As may be apparent from the above chart, the share going to compensation of employees dipped in the early years of the expansion, but it didn’t hit record lows. This could happen even as the share of national income going to wages and salaries was at all-time lows because spending on non-wage compensation such as health insurance and pensions has risen. The 2.8 percentage point decline in corporate profits’ share of national income since 2012 was due mainly to a 2.2 percentage-point rise in employee compensation’s share, with wages and salaries accounting for virtually all of that increase. Labor’s share is rising again! As my fellow Bloomberg Opinion columnist Tyler Cowen wondered in July, why aren’t people celebrating?

Maybe we should be, although it’s probably worth waiting a few years to see if the trend survives another turn of the business cycle. Also, while employee compensation’s share of national income is back to just about its long-run average, wages and salaries’ share is still lower than it ever was before 2006. Mainly because employers in the U.S. spend so much money on health-care, it may not feel like labor is gaining on capital, even if according to the national income data it is.

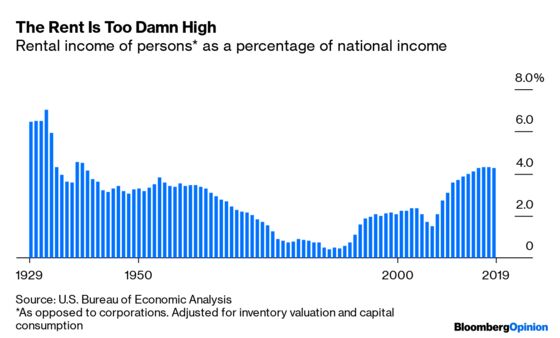

Something that has gotten much less attention in the capital versus labor discussion is the rise of rent. The next-biggest gainer in national income share since 2012 — and thus presumably the next-biggest contributor to the fall in corporate profits’ share of national income — has been “rental income of persons.”

More than 90% of this rental income is, as you might expect, housing-related. Most of it is the “imputed rent” that homeowners are assumed to be receiving from, um, themselves for the privilege of living in their own homes (aren’t economic statistics fun?). The rental income increase over the past decade thus can’t be attributed to the fall in home ownership and rise in renting in the aftermath of the housing bust, but it probably does have something to do with high housing costs.

Super-expensive housing in coastal metropolises isn’t just making life tough for middle-class and poor people there. It may also be squeezing corporate profit margins as companies have to pay more to get skilled workers to come to and stay in places like New York and Silicon Valley.

Gross domestic income, which is national income plus and minus a few things, should in theory be equal to GDP, but it never quite is. Also, the bars in the chart go up to 100.4% in 1932 and 1933 not because of some quirk in national income accounting but because corporate profits were negative in those years and our charting software doesn't know what to make of a negative number in a stacked-bar chart.

As distinguished from corporations and government entities, for which there is no breakout of rental income; nonprofits are included, though.

The big increase in the late 1980s may have had more to do with changes in the tax code that reduced the advantages of being taxed as a corporation rather than an individual, thus increasing the share of rental income that was going to individuals and to partnerships and limited liability companies that are taxed as individuals.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Sarah Green Carmichael at sgreencarmic@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.