As Bad as 2008? The Market’s Fear Index Is Starting to Think So

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- How afraid should be you amid the coronavirus outbreak, at least as far as the stock market goes?

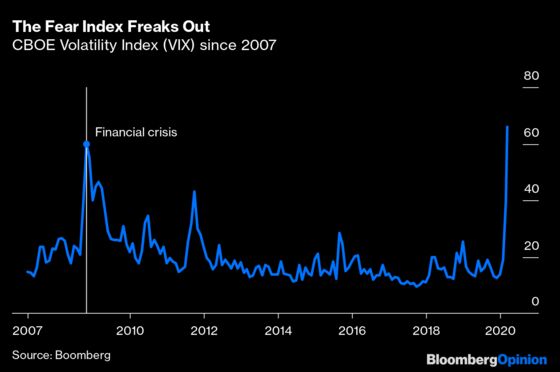

One of the best ways to gauge how much fear is in the market is the CBOE Volatility Index, better known as the VIX. The VIX, sometimes referred to as the fear index, is derived from the price of S&P 500 index options; it provides a more or less objective measure of real-time sentiment and market stress -- and it as it highest since the 2008-09 financial crisis:

Here are some thoughts that might put this into perspective:

No. 1. The VIX might serve as a leading buy indicator: The VIX chart cited above give us a sense of exactly how much fear is occurring in the market right now. Some of this is a function of what we don't know; some is simply a recognition that corporate revenues and profits are going to be pressured, perhaps a lot. The big question is for how long.

The chart above compares this VIX spike with several others since 2007. It suggests this is a much quicker run to 60 than in the past. This implies -- though by no means guarantees -- that when the pandemic runs its course the return will likely be just as quick.

No. 2. It feels as if it is minor until it isn't: During a long bull market, buying the dip becomes muscle memory. Every buy gets rewarded and most sells get punished, at least eventually. Lots of economic and market upheaval can create some concern among investors, though the standard response is that stocks tend to climb a wall of worry. “The trend is your friend,” the technicians says, but the older ones always add “Until the bend at the end.”

No. 3. Things can last longer -- often much longer -- than expected: Bear markets often begin when corporate profits begin to reflect a slowing economy. If you doubt this, just consider the bull market, which lasted 11 -- or seven years, depending on how you measure it -- which is much longer than most analysts and commentators expected.

Typically, the source of the bad news comes from inputs that take a long time to be reflected in markets. For example, a change in interest rates takes several months or even quarters to be felt in the broader economy; fiscal stimulus or austerity can take years to work its way into gross domestic product. Markets see recessions long before economists do.

Markets are a probabilistic discounting mechanism; they reflect the collective effort to make a reasonable guess about future cash flows and profits against the backdrop of an unknowable future. The inputs come from people filled with all of the usual human cognitive biases and foibles. Each new piece of information works its way into the market and is manifested in prices. If the news is consistently worse than expected, markets gradually get worse. Very often the headlines start out behind the curve as to how bad things will get, but they also tend to then overshoot on the other side; in other words, they stay bad even as the market recovery has already begun.

No. 4. Do not confuse cyclical versus secular: During the course of a long-term secular market, there are always large counter moves. Consider the rallies that occurred during the bear markets of 1968-1982 or 2000-2013; also, look at the sell-offs during the 1946-66 or 1982-2000 bull markets.

Pay attention to the qualitative context of what is driving the economy and therefore future corporate profits. If it is temporary -- as a pandemic is likely to be -- then we want to look through to the end of the lockdown and the recovery.

No. 5. Buying into a sell-off is really hard: “Everyone wants to be a contrarian” could be my favorite sentence of all time. How many traders wish they could put their emotions aside, follow a few charts and buy at the market lows? Humans are herding social primates, a species that evolved over time with group cooperation as a survival strategy. You have been wired to not fight the crowd; it is incredibly uncomfortable to do so.

The bottom line is this: We have no idea how much worse this gets in terms of public health or for the economy. But once the scope of this crisis has been accounted for, the market is likely to identify it before anyone else.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Barry Ritholtz is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is chairman and chief investment officer of Ritholtz Wealth Management, and was previously chief market strategist at Maxim Group. He is the author of “Bailout Nation.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.