Winners and Losers This Time Are Different From 2008

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The human inclination to compare the past and the present is irresistible. So looking for parallels between this economic downturn and the financial crisis of 2008-09 is natural, particularly given the alarming levels of unemployment and declines in economic output in both events.

But as the worst of the coronavirus health crisis eases, at least for now, we're seeing that there are meaningful differences between the last downturn and this one. The epicenters of the last crisis -- the housing market, household finances and the banking system -- are holding up better so far, while areas of strength coming out of the Great Recession -- the oil industry and urban real estate -- look murkier. This is due to differing economic fundamentals coming into the crisis, policy choices made by Congress and technological change.

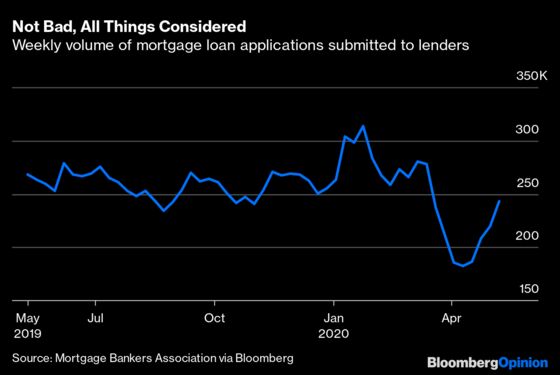

No industry epitomizes the difference between this crisis and the last more than housing. Although the market collapsed in March and early April as shelter-in-place orders went into effect -- scaring investors with memories of the severity and duration of the meltdown a decade ago -- we've seen several indicators suggesting activity has bounced back during the past month. Online real-estate brokerage Redfin says buyer demand has already recovered to pre-coronavirus levels. Mortgage-purchase applications have increased for four weeks in a row, and are now down only 9.5% year-over-year:

Meritage Homes, which develops luxury and senior housing, says that momentum built during the latter half of April has carried over to May, and it expects May orders to match last year's. A stable housing market with 15% unemployment may not be sustainable over the long run, but it's what we have at the moment.

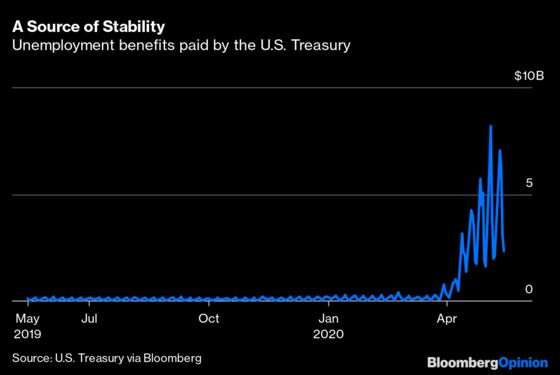

Another area of surprising stability so far, given the high level of unemployment, is household finances. This is mostly due to the $2 trillion CARES Act passed by Congress. Between the one-time relief checks sent to Americans and the additional $600 a week in federal unemployment benefits, most unemployed workers, particularly at the lower end of the income scale, have been made whole so far:

Through May 13 there's only been a 2.1% decline in the share of apartment households who paid rent, suggesting that most households continue to be able to pay their bills. This is good news, but it's important to note that millions of Americans are still waiting for relief with unemployment offices in many states struggling to process the flood of claims they've received. But unlike the Great Recession, there was no worrisome buildup of household or mortgage debt before this crisis. Fiscal policy has largely plugged the gap for households so far. There remains at least the possibility that we can get through this crisis without a huge wave of mortgage defaults and household bankruptcies.

At the same time that the housing market has stabilized, and with household balance sheets backstopped by government support, banks are in better shape and have bigger capital buffers to absorb losses, thanks to the regulatory changes adopted after the Great Recession. In order to return capital to shareholders, the major U.S. banks had to pass stress tests last summer that included the possibility of the stock market falling 50% and housing and commercial real estate prices declining 25% to 35%. None of these have happened so far. Banks pre-emptively suspended their stock buyback programs in March once it was clear how severe this crisis would be. None of the major banks have cut their dividends, let alone raised new capital, to weather this crisis. And the Federal Reserve has taken significant steps to ease stresses in both the banking and financial systems. Although banks have obviously been dinged by this crisis, they are not the source of it, an important difference as we think about the recovery process.

But some of the areas of strength coming out of the Great Recession look weak today. In 2008 oil demand suffered a temporary setback from the crisis but recovered quickly, as did oil prices. The price of West Texas crude oil was perched at a solid $80 a barrel in October 2009, the month that the U.S. unemployment rate peaked at 10%. That hasn't been the experience in this crisis, with the market oversupplied amid weak demand, disagreements on output among producers and the prospect of electric vehicles displacing gasoline-powered ones in coming years. Oil-producing regions in the U.S. were some of the first to emerge from the Great Recession, but are unlikely to do the same this time around.

And although coastal cities and their robust job markets were sources of strength coming out of the Great Recession, the opposite may end up being the case this time around. The young knowledge workers who flocked to high-cost cities during the past decade are older and might use this crisis to accelerate their plans to leave cities for cheaper housing markets. And companies, rather than looking to recruit the next generation of college grads to those same cities, might use this crisis to encourage more remote work or job shifts to lower-cost cities, a trend that has been underway for a few years. Cities such as New York and San Francisco still have plenty of strengths but their fortunes might plateau as this economic restructuring plays out.

These are the types of trends to watch as the initial shock of March and April recedes and the economic data turns more mixed in the weeks and months to come. Even if the recovery is as slow and prolonged as it was in the years after the Great Recession, the industries and regions that lead the U.S. out won't be the same as last time.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Conor Sen is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is a portfolio manager for New River Investments in Atlanta and has been a contributor to the Atlantic and Business Insider.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.