(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s like the 2012 euro crisis all over again, as Europe awaits a decision on Italy’s sovereign-debt rating from S&P Global Ratings after Friday’s market close. The country’s current BBB (negative outlook) is just a couple of notches above the junk-bond category, so there’s plenty of investor interest in what happens. Moody’s Investors Service will assess its rating, which is one notch lower, next week.

It doesn’t make much sense that the finances of one of the world’s largest economies are beholden to Delphic judgments from commercial agencies.

It’s unlikely that Italy will be cut to junk. Even if it is, the European Central Bank will keep buying Rome’s debt. But an eventual loss of the country’s investment-grade rating would matter. Many bond funds would have to sell Italian sovereign debt and other related credits. It could cause financial distress to the nation’s finances, and to the European Union.

Surely we need a more realistic, and more flexible, rating system to avoid a credit shock during the Covid-19 crisis — which is no individual country’s fault.

Both the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank appreciate the dilemma and are making efforts to either purchase higher-quality junk-rated debt, or to accept it as collateral, but we need to change the way we rigorously evaluate credit risk. What’s the point of creating “fallen angels” — the name given to bonds that have dropped below investment grade since the pandemic struck — if the world’s biggest bond buyers then have to implement special measures to ignore the downgrades?

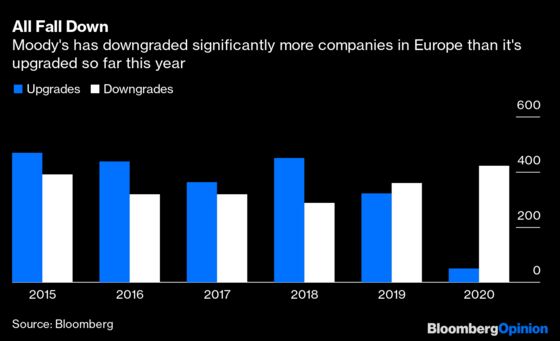

S&P downgraded six times more companies in the first quarter of 2020 than it upgraded. Moody’s has taken negative rating action against nearly a quarter of the companies it classifies as speculative grade, largely because of the coronavirus. It expects the gap in creditworthiness between junk and investment grade to widen. This deluge needs to be managed before it overwhelms even the best efforts of the world’s central bankers.

Credit ratings are too blunt an instrument right now, given the vast — and necessary — escalation of debt. The requirement of investment-grade bond indexes to only allow specifically rated bonds is an accident waiting to happen. A wave of more downgrades is coming.

The agencies could help by adopting new methodologies to make it less binary for bond indexes and fixed-income funds when credit is downgraded. With so much debt being reclassified downward, we need a system that considers creditworthiness relative to other sovereigns and corporates, rather than looking at individual cases in an absolute way as we do now.

With half of America’s investment-grade companies sitting in the BBB bucket (just above the junk divide) and more than 200 billion euros ($216 billion) of European credits close to the edge, there’s an overwhelming need to address this anomaly.

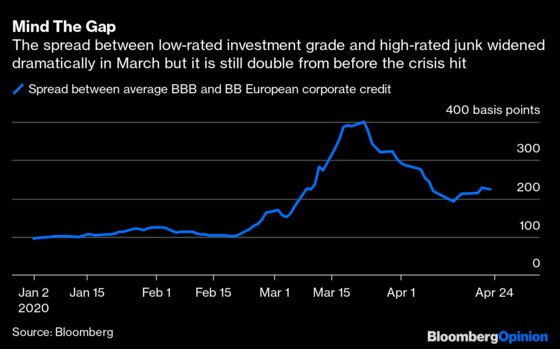

The penalty for falling on the wrong side of the divide is too severe. It has a sizable effect on credit spreads (the difference between a bond’s yield and that of its benchmark), with a one-notch downgrade often being punitive. The average spread between junk BB-rated European credits and investment grade BBB stuff blew out to almost 400 basis points from an average of about 100 basis points at one point during this crisis.

The credit markets themselves function pretty well in determining how a bond should be valued. Netflix Inc., for example, managed to achieve its lowest-ever yield Thursday for a $1 billion debt sale despite only having a relatively lowly BB- junk rating. That makes sense for a company whose business model is suited to people staying at home. Investor demand was more than 10 times what was on offer. On the flip side of the coin, Carnival Corp., the ailing cruises company, had to pay nearly 12% to raise funds in March despite being technically still investment grade. Investors know how to price this debt.

In fairness, the ratings agencies can’t provide real-time credit validation when they rely on actual data rather than presumption. But they need to adapt to the changing reality of Covid-19 — and quickly.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Marcus Ashworth is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European markets. He spent three decades in the banking industry, most recently as chief markets strategist at Haitong Securities in London.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.