(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Coronavirus self-isolation is fostering a growing dependency on Amazon.com Inc. But it’s also refocusing attention on the human cost of having the entire stock of the “Everything Store” merely a click and a day away from your front doorstep.

Amazon workers at a fulfillment center in Staten Island, New York are on strike, saying the company has not been responsive to safety concerns and demanding that the facility be closed for two weeks and sanitized. In Italy, Amazon reached an agreement with workers last week to provide additional virus containment measures and end an 11-day strike. Elsewhere, France’s labor minister has demanded an improvement to the working environment for the firm’s employees, saying that “protection conditions are insufficient.”

The comments came a week after Chief Executive Officer Jeff Bezos outlined many of the company’s efforts to blunt the effects of coronavirus in an open letter posted on Instagram, including boosting worker pay in the U.S.

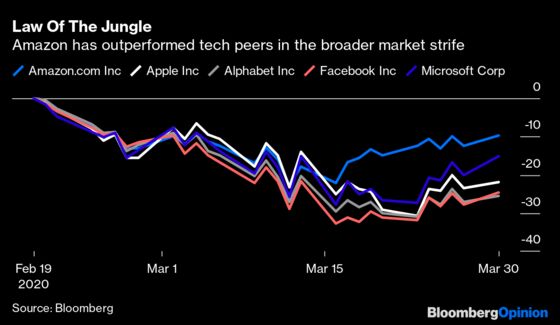

Demand for Amazon delivery services has, meanwhile, given its stock better protection than its tech peers from the recent market pummeling. The shares are down 9.4% since Feb. 19, compared with the average 22% decline of Apple Inc., Google parent Alphabet Inc., Microsoft Corp. and Facebook Inc.

The logical conclusion is that Amazon should be doing a lot more to protect its workers. It can afford to: It’s sitting on $55 billion in cash and is expected to generate another $34 billion of free cash flow this year.

But the stark reality is that Amazon’s e-commerce business isn’t very profitable. Its cloud computing operations are the money-printing machine. That unit will enjoy a 28% operating margin on sales of some $46 billion this year, helped by the surge in internet usage caused by people logging on from home for longer, Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Jitendra Waral estimates. The company’s other $288 billion of revenue will generate operating profit of as little as $3 billion.

That razor-thin profitability hints at the strict cost control upon which Amazon relies to ensure goods are delivered cheaply and quickly. Unfortunately, cost control is often a euphemism for low wages, ungenerous benefits and a squeeze on suppliers. A 2018 analysis by the Economist found that after Amazon opens a storage depot, local wages for warehouse workers fall by an average of 3%. Nor does that inspire much confidence in Amazon’s latest moves: The recently announced $2 per hour pay bump will hold only until April, while the doubling of overtime pay will expire in May — for now, at least.

What’s more, workers’ negotiating power is likely to be eroded by the coronavirus crisis. The peak of U.S. labor exploitation came during the Great Depression, when everyone was scrambling for jobs, which in turn ultimately turbocharged labor organization. The number of jobseekers today is now at the highest in a half-century: A record 3.28 million Americans filed for unemployment benefits in the week of March 21, compared with 211,000 just two weeks earlier.

Bezos explicitly targeted those newly unemployed in his Instagram letter, explaining that the company would hire 100,000 additional employees to cope with increased demand. So the fact that only 100 people from a workforce of 4,000 at the Staten Island site are striking is either indicative of minimal discontent or a fear of retributive job losses (the only unionized Amazon employees in the U.S. are in its film and TV productions). As if to underscore the point, Amazon fired the worker leading the strike on Monday, ostensibly for “violating social distancing guidelines.” According to Amazon, only 15 people ultimately demonstrated in the strike, of whom just nine were actual employees.

The working conditions at Amazon are partly our fault as consumers. The company has groomed us to rely on next-day deliveries at no extra cost, at least if we have a subscription to its Prime service. We probably don’t ask what it takes to make that work. For all of its Kiva warehousing robots and efforts with drone distribution, Amazon still depends on hundreds of thousands of human workers around the world. You know when you receive a massive box containing just a small parcel? That’s not because of some algorithmic misstep; it’s a person in a warehouse making a quick decision on how best to deliver your package.

Amazon can for sure afford to lessen the load on its workers with better pay and working conditions, but only because of the massive success of its cloud business. It's harder for rivals to do so and still turn a profit. The dilemma is accentuated by, but not peculiar to, the current crisis. If that’s to change, we as customers must also be prepared to pay higher prices — and that’s as true in good times as it is in bad.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Alex Webb is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Europe's technology, media and communications industries. He previously covered Apple and other technology companies for Bloomberg News in San Francisco.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.