(Bloomberg Opinion) -- A “great day for European solidarity” is how Germany’s finance minister described last week’s $590 billion euro-area virus rescue package, clinched even as Europe’s North and South haggle over the cost of cleaning up the economic wreckage left by Covid-19. The package would allow countries to borrow from the euro region’s rescue fund, the European Stability Mechanism, for health-care spending without policy constraints, up to a certain amount.

The focus on money is understandable, given the looming recession that’s expected to be deeper than the crisis of 2008. But it obscures a glaring failure of the European Union that may have made both the human and financial cost of the pandemic worse: A lack of coordination and collaboration in health-care policy.

Despite a common market, a (mostly) common external border, and a common health-care challenge in the shape of an aging population, the EU’s 27 member states have scattered like mice when fighting the coronavirus. At the beginning of the crisis, Italy, the first and worst hit in Europe, begged its partners for masks and equipment — not money. The response was a string of border closures and the hoarding of medical supplies for domestic consumption. By the time France, Spain and Germany instituted their own lockdowns, it was clear there would be 27 different responses to the coronavirus, not one “European” one.

Normally, it’s the lecturing tone of the European Commission, the EU’s executive body, that would set the line for countries to follow. But health-care policy is jealously guarded by national governments, which have never given Brussels technocrats full powers to dictate how hospitals or drug supplies are managed. The lesson of Covid-19, supposedly, is that Leviathan’s nation-state knows best.

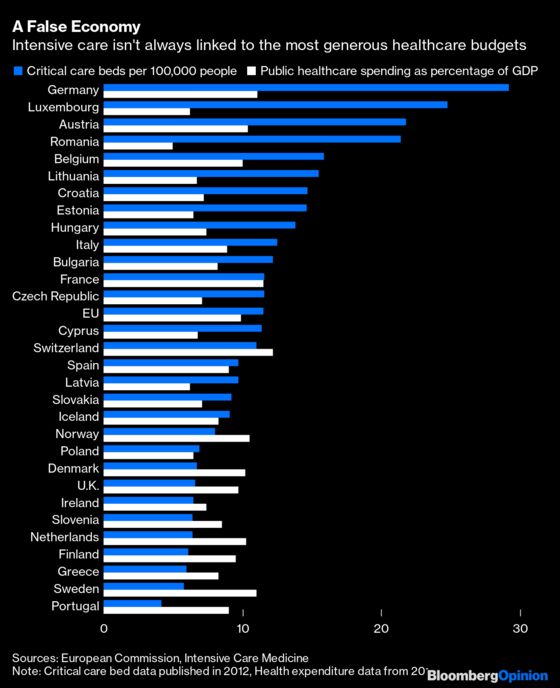

Yet the uneven death toll as it now stands suggests Leviathan isn’t always well-equipped against epidemics. Countries that reacted early relative to their Covid-19 outbreaks — Austria, Denmark, Greece — appear to be doing better than those that reacted relatively late, such as Italy or Spain. A thrifty yet decentralized country like Germany, combining high intensive-care capacity with specialist industrial health-care firms, seems to be coping better than France’s well-funded but centralized system that’s ferrying patients by high-speed train to less-hit regions in order to ease the burden. Some countries have better access to masks and tests than others.

There are complex factors that seem to make one country more Covid-resistant than another. They go beyond a North-South divide, or health-care spending as a percentage of GDP. Some factors, like population density, can’t be helped. But the EU should have been ideally equipped to fight a lot of these disparities. Properly-funded information-sharing and coordinated disease surveillance between countries would have made swift responses possible. A pooling of medical supplies would have better allocated existing resources for things like test kits, masks and ventilators, while combined purchasing power could have bought more for less.

It’s not just about hindsight, but foresight: The EU should also be a contender in the all-important global race for a vaccine, given it could pool national budgets to fund at least $30 billion in estimated research and manufacturing costs to get there. (It’s also home to several drugmakers already working toward that goal, such as France’s Sanofi or Germany’s CureVac AG). The bloc’s resources are often tied up in red tape and bureaucratic silos, though, as the furious departure letter by top EU science official Mauro Ferrari indicated last week. His reported push to redirect 2 billion euros ($2.2 billion) of annual “bottom-up” long-term research funding toward Covid-19 ruffled feathers and resulted in a unanimous request for his resignation from the European Research Council, but it’s clear that redirecting the flow of money in a crisis isn’t the EU’s strong point.

“More Europe” is an understandably hard sell right now, and few member states will be in a rush to transfer more powers to Brussels. But existing tools can and should be beefed up. Nine EU countries including France, Italy and Spain explicitly called last month for the Commission to do more on establishing common guidelines and the sharing of data and information. They could start with the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control, which has a paltry budget of around 60 million euros, a long way off the U.S. equivalent’s budget of $11 billion. Medical equipment and testing capacity should be funded across the bloc as lockdowns start to be lifted. That may well require a lift to the EU’s budget.

Not all forms of top-down control make sense in this crisis: Regional health authorities have led the way in some countries, more so than even national governments. But as the London School of Economics’s Joan Costa Font puts it, collective action between countries is obviously beneficial when facing a pandemic that doesn't respect borders — not least in the EU, where a highly-integrated economy means it’s in every country’s interest to have healthy neighbors. If the focus on money fails to lead to more burden-sharing of health information and resources, European states will face a long road out of lockdown.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Lionel Laurent is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Brussels. He previously worked at Reuters and Forbes.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.