(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The coronavirus may mercifully pass over the very young, but of all the age groups that emerge from this crisis, they will be most marked by it. The longer schools are closed, the deeper those marks will be. Yet reopening is both urgent and fraught, because there’s no simple way of going back to the way it was.

Even if this particular pandemic is novel, history has taught us that the effects of interrupting education can be profound. During World War II, the last crisis that is remotely comparable to today’s, bombing damaged about one in five schools in London, while another two-thirds were requisitioned for government use. Millions of children were sent to the countryside for safety. There were shortages of books and stationary supplies; rural schools had to share classrooms with evacuees, so groups of students were staggered between morning and afternoon learning sessions. By January 1940, only a quarter of children in London were receiving full-time education.

The war had an impact not only on education quality but on children’s future career paths and earnings. One study compared two cohorts of students who reached the age of 10 during or immediately after the war — one in Austria and Germany, the other in Sweden and Switzerland, where civilians faced far less disruption. It found educational attainment lagged in children whose learning was interrupted by war.

Nobody had Zoom or ShowMyHomework during the Blitz, it’s true. The world of learning has changed dramatically over the past several decades, but not all children are benefiting from that in the same way. Some happy homes are buzzing with video learning, homework scanning and board game-playing industriousness. For students from less privileged backgrounds, however, the routine and structure of classroom learning is difficult to replicate at home.

It’s not just a matter of equipping children with laptops or tablets and internet access. Having a dedicated work space, family stability and support, and good nutrition and sleep habits can be the difference between children who maintain some level of productive learning and those who fall further behind or lose interest in schooling altogether.

In homes where abuse, alcoholism, depression, disability or marital breakdown — not to mention unemployment and Covid-19 illness — are prevalent, concentrated learning becomes almost impossible. The interruption can also have a devastating effect on children with mental health issues and those with special education needs.

Teachers at Marlborough Science Academy, a well-run state-funded senior school in a largely middle-class part of Hertfordshire, had one week to prepare for the move to digital teaching. Jo Bustin, who has taught at the school for 22 years and has a senior leadership role in safeguarding, figures that most of the children in her school will be fine, but it’s already apparent that those who are in unsupportive or unstable homes lose out.

The school remained open for students of front-line workers and students seen as vulnerable, but most of those invited to attend in person don’t. “This is one of the greatest experiments I’ve ever seen in education, because we are basically saying, ‘Here it all is, and it’s up to you to decide whether you want to engage,’” she told me.

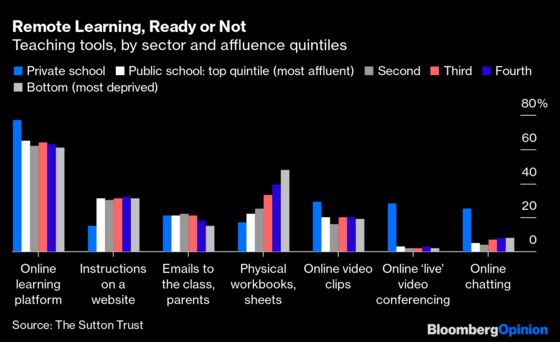

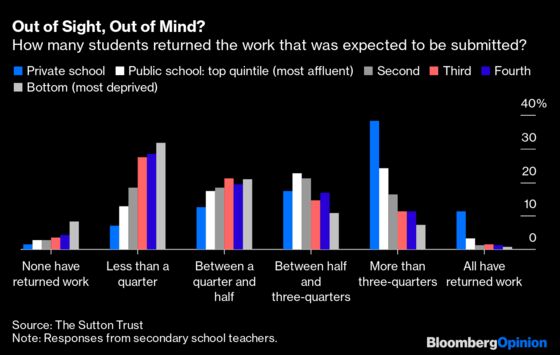

The level of affluence seems to make a difference on students’ experiences as well. An April report by the U.K. charity Sutton Trust found an alarming gap in remote learning experiences, with privately schooled kids twice as likely as publicly schooled (in the American sense of state-run) students to receive daily remote instruction.

Even those teachers who have adapted to digital instruction say they can’t connect with students in quite the same way. One former teacher explained that once you get a group of kids on Zoom, one will always misbehave — it doesn’t matter how privileged the family. Sometimes kids just don’t want to learn or stay on task. Some councils advise against live video teaching because of the potential for inappropriate dress, language or other problems, so classes are recorded. And teachers say it’s hard to enforce assignments; they can’t exactly hand out detentions.

For Britain, school closures compound preexisting problems. The U.K. education system is a hodgepodge of schools running the gamut from failing to first rate. Deprivation is more common than many realize. About a fifth of children between the ages of four and 15 are entitled to free school meals, generally because their families receive some kind of income support.

A 2017 analysis found that pupils from economically disadvantaged backgrounds were on average 18.9 months behind the rest of their peers at the end of secondary school. This education gap — which translates into outcomes such as poorer health, lower average earnings and a greater propensity to be involved in crime — is often cited as a major contributor to Britain’s stagnant productivity and low levels of mobility.

The public health implications of restarting school amidst the coronavirus crisis have been much debated, but the weight of evidence is now leaning toward finding a path to reopening sooner rather than later. Schools are not major vectors for the virus spreading — as a recent study from University College London researchers, as well as research in Iceland and experience in Asia, suggests. And much of the labor force returning to work depends on parents being able to send their kids to school.

That doesn’t mean schools can return to their pre-virus normal. Denmark started with primary schools and kindergartens. Desks are placed further apart. Pupils are separated by the requisite two meters (though how that works for very young children isn’t clear), drop-offs and pickups are staggered, parents are not allowed in the building and toys are all rigorously washed.

More new guidelines will surely be needed, along with plans to help close the educational gaps that widened during this period. For children in homes with vulnerable adults — those with underlying health conditions who have been told to continue self-isolation, for example, even after some businesses reopen — alternative provisions may need to be made. Schools also have what U.K. law calls a “duty of care” to provide safe working conditions for teachers, and teachers unions have threatened strikes if schools reopen against medical advice.

The longer it takes to work out a way back to school, the greater the risk that inequalities that have long bedeviled Britain’s education sector will widen. Families that stretched to afford private education may be unable to do so, putting additional strain on an already resource-poor state sector and forcing private schools to lay off staff. The demands on the U.K. Treasury are great, and education could lose out as the economy contracts.

If so, this virus is likely to have a very long tail indeed.

Elaine He contributed graphics to this piece.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Therese Raphael is a columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. She was editorial page editor of the Wall Street Journal Europe.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.