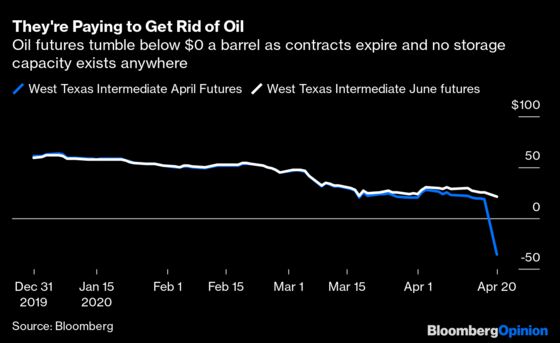

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Global market participants were fixed on the oil markets Monday as West Texas Intermediate crude futures crashed to negative — yes, negative — $40.32 a barrel from $18.27 on Friday. What this means is that owners of those futures were willing to pay someone $40.32 a barrel to take those contracts off their hands. Don’t look for historical comparisons, because there are none. And while yes, the move was shocking, it can largely be explained by technical factors, with traders fleeing the May futures contract ahead of its expiration Tuesday so as not to get stuck actually holding physical barrels of oil with no place to store it. The June contract was more in line with reality, trading at around $21.50 a barrel. Still, the episode speaks volumes about the current state of financial markets.

At the least, the craziness in oil — coming just a week after the historic deal between OPEC, its allies and Russia to curb production — underscores how the problems facing the global economy from the coronavirus pandemic won’t soon go away despite the recent rebound in equities that pushed major indexes above their lows of 2019 set last June. After all, it was also just over a week ago that the International Monetary Fund forecast the worst global downturn since the Great Depression. If true, demand for oil isn’t likely to make a comeback anytime soon, especially with lockdowns still in place in much of the world. The strategists at Morgan Stanley in their weekend research note made clear “sustainable re-opening” of economies and business require four key components: 1) adequate surge capacity in hospitals, 2) public health infrastructure to support testing, 3) robust contact tracing to curtail “hot spots,” and 4) widespread access to serology testing to determine who is already immune to the virus. “Even then, however, the return to work will be slow, with our economists not expecting to see pre-recession levels of output for U.S. or global growth” until the fourth quarter of 2021, Morgan Stanley strategist Ed Sheets wrote in the note.

There’s been a lot of optimism lately in markets that “the worst is behind us” when it comes to the pandemic. Even if true, it’s unlikely the economy will bounce back to “normal” with the flick of a switch. It’s not that the Morgan Stanley strategists are bearish. Rather, they are just noting that attempting to reopen the economy before their four key prerequisites are in place “would inject significantly more uncertainty” around whether the worst for the economy could be over as soon as the end of June. “Such a scenario would pose a clear risk to our positive bias towards current markets,” they added.

A BULL MARKET IN NAME ONLY

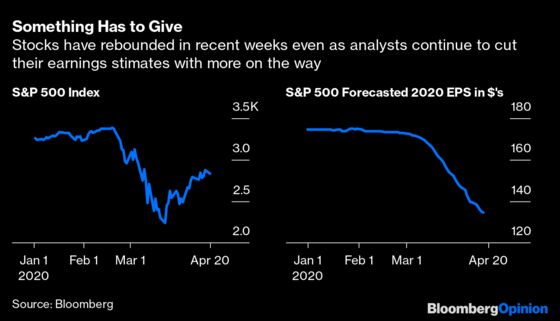

Even with a 1.79% pullback on Monday, the S&P 500 Index is up 26.2% from its closing low on March 23, meaning it has met the technical definition of being in a bull market. And although it’s still down for the year to the tune of about 12.6%, it’s up 2.87% from last year’s low on June 3, which is astonishing given that analysts have slashed their corporate profit estimates for this year by 23% already and first-quarter earnings seasons is only one week old. “Keeping in mind that earnings drops in recessions average in a range of down 25% to 30%, we believe there are larger downward revisions to come,” Bloomberg News quoted Cantor Fitzgerald strategist Peter Cecchini as saying. The smart money certainly seems to think estimates will be cut even more, dragging down stock prices with them. Hedge funds and other large speculators boosted their bearish bets on S&P 500 e-mini futures by 50% in the week ended April 14, to about 218,000, contracts, the most since February 2016, according to Bloomberg News’s Elena Popina. At the same time, money fund assets have surged to $4.52 trillion from around $3.6 trillion at the end of January, according to the Investment Company Institute. Clearly, the recent rally isn’t convincing many people that the worst is over.

HAVENS REMAIN IN DEMAND

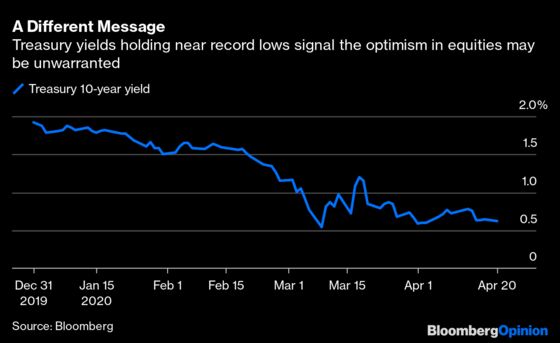

What makes the rebound in equities even more of a head-scratcher is that the move hasn’t really been confirmed by other markets. Although the credit markets have firmed, with corporate-bond yield spreads tightening from Armageddon-like levels, haven assets such as U.S. Treasuries, gold and the dollar remain in high demand. At 0.63% on Monday, yields on 10-year Treasury notes are hovering around their all-time lows despite the Federal Reserve having pulled back its support by reducing purchases over the last week. “We had the great lockdown but it’s not going to be a great reopening,” Priya Misra, global head of interest-rate strategy at TD Securities, told Bloomberg News. “The reopening will be phased and gradual and there might be sudden stops along the way.” At $1,707 an ounce, gold is closer to its high for the year of $1,769 than its low of $1,478 in February. The same is true of the dollar, which rose on Monday to bring the Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index’s gain for the year to 5.08%. That makes 2020 already the best year for the greenback since it strengthened 8.98% in 2015. Looking beyond oil in the credit markets, copper is still down 18% for the year even after gaining almost 10% from its low on March 23. The stock market tends to grab the headlines and be viewed as the ultimate arbiter of risk appetite, but doing so risks missing the broader picture.

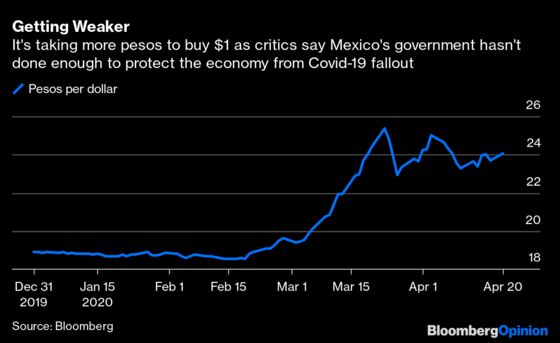

CREDIT RATINGS MATTER FOR MEXICO

It’s well known that markets are much quicker to react to declining creditworthiness than the credit-rating companies. This is why, by the time a borrower is actually downgraded, there often is little market reaction. Sometimes, though, markets do get surprised, which seems to be the case with Mexico. The nation’s stocks, bonds and currency all fell after Moody’s Investors Service downgraded its ratings for both the government and Petroleos Mexicanos late on Friday. Moody’s decision was somewhat expected, as it came on the heels of downgrades by S&P Global Ratings and Fitch Ratings, but the cuts still highlighted the relative weakness of Mexico, according to Bloomberg News’s Justin Villamil. With a drop of 1.61%, the Mexican peso was the biggest loser against the dollar of 31 major currencies tracked by Bloomberg after the ruble, which fell 1.76%. Moody’s cut Pemex, the world’s most indebted oil major, to junk, and cited the oil company as one of the reasons for a dim sovereign outlook. There also is concern that Mexico has done too little to protect its economy from the coronavirus pandemic. The government so far has limited its response to public-works projects, low-interest loans to the poor and budget tightening, which helps to explain why the peso has depreciated some 22% this year.

TEA LEAVES

The real estate industry is built on optimism. For most Americans, buying a house is the biggest investment they will make in their lifetimes. So before shelling out $270,000 for the average U.S. home, consumers better feel pretty secure in their employment and income stream. The problem is, the coronavirus pandemic has suddenly made many Americans feel less secure, with more than 20 million filing for unemployment insurance in recent weeks. Plus, with social-distancing rules in place most everywhere, it’s almost impossible to get out and actually buy a home. We’ll get a glimpse of just how bad things are for the housing market, which accounts for a big chunk of the economy, on Tuesday when the National Association of Realtors provides an update on existing home sales for March — which was when the lockdowns were just starting to be put in place. The median estimate of economists surveyed by Bloomberg is for a decline of 9% after February’s 6.5% jump. Bad, but not as extreme as the 20% declines we saw during the financial crisis a decade ago. But with all the data these days, the risk is to the downside. “Social distancing and bank-branch and legal-office closures made it nearly impossible for buyers, sellers and other agents to get together at the closing table in many heavily populated parts of the country,” Bloomberg Economics notes. “These real estate closures will be delayed until restrictions are lifted.”

DON’T MISS

This Crisis Shouldn’t End Like the Last One: Mohamed El-Erian

Central Bank Independence May Not Survive the Virus: Clive Crook

Texas, Like OPEC, Can't Turn Back Time for Oil: Liam Denning

Dot-Com Prices in a Pandemic Make Fools of Us All: John Authers

Coronavirus Reverses Brazil's Economic Revolution: Mac Margolis

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is the Executive Editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global Executive Editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.