(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The instruction given by Boris Johnson to the British people on March 23 was dead simple: “You must stay at home.” The pithiness and urgency of that message, the alarming rise in deaths, and the U.K. prime minister’s subsequent hospitalization with Covid-19 all reinforced the instruction. People got it.

Some say it was too successful. Many Britons don’t seem to want to come out of lockdown now. The all-important R number — the average number of people infected by one person — is now said to be below one. But how to keep it there while getting people back to work?

Johnson’s task on Sunday, when he’ll set out the circumstances under which people can resume parts of their old lives, will require far more granular and sophisticated communication. There’s only one way into lockdown, but multiple routes out.

The government’s grave errors in the early stages of the pandemic make the reopening perilous politically. Having been slow to increase testing, Britain improved during April, but it’s a long way from the mass examinations needed to provide confidence in a steady return to normality. The other component of a successful unlocking strategy — contact tracing — is being trialed on the Isle of Wight. But the U.K.’s homegrown solution may prove inferior to the Google and Apple Inc. technology that countries like Germany and Switzerland opted for.

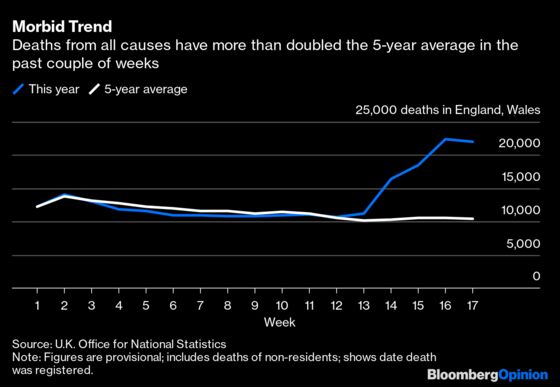

Britain’s abject record in fighting the virus leaves Johnson very little margin for error. The U.K. death toll has surpassed that of Italy, making it the worst-hit country in Europe, and second globally to the U.S. The official number of more than 30,000 fatalities is probably far smaller than the real figure. Data from the Office for National Statistics show that over 42,000 more people have died than is normal since mid-March.

As Keir Starmer, the opposition Labour Party leader, asked Johnson on Wednesday: “How on earth did it come to this?” The government has two answers to that question, neither very satisfying.

The first is that it’s too early to make conclusive judgments about death tolls. The relative numbers between nations may look different some months down the road when a full accounting is made. Even so, there’s little chance that Britain’s death rate will not look horrible when compared with Germany, South Korea and many other countries. While there may be an argument for taking international comparisons with a grain of salt, U.K. ministers have been using such information at every news conference for weeks.

The government’s second answer to Starmer’s question — that it has been “guided by the science” — looks even more dubious, given all of the confusion and mystery around this guidance. On Monday it bowed to pressure to release the names of members of the influential Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), after growing criticism about the dangers of shrouding the advice in secrecy.

On Tuesday, one of the most prominent SAGE members, Imperial College professor Neil Ferguson, resigned after the Daily Telegraph reported that he had violated social distancing rules to meet his married lover. It was Ferguson’s controversial models that most influenced the government’s lockdown policy. He apologized and said he’d figured that since he’d had Covid-19 and completed his period of self-isolation he was immune. Scientists aren’t entirely sure what immunity the virus confers, so that’s an odd statement from one of the government’s chief advisers on the pandemic.

The timing of the Ferguson disclosure is significant too. A backlash against Johnson’s lockdown — and the evidence on which it was based — has been building, especially among members of Johnson’s Conservative Party. Steve Baker, an arch-Brexiter, says the restrictions are “absurd, dystopian and tyrannical.” Jonathan Sumption, a former U.K. Supreme Court judge, wrote a column calling the lockdown “without doubt the greatest interference with personal liberty in our history.” That was applauded by Tesla Inc.’s Elon Musk.

Ferguson’s indiscretion is a gift to this campaign against restrictions. It doesn’t help confidence in the government’s policies if the man known as “Professor Lockdown” wasn’t following the advice he repeatedly trumpeted on national media. His resignation provided an opportunity to question not just his judgment but his scientific models.

Johnson will want to respond in some way to this pressure to restore economic activity from the right of his party, the same people who delivered him power. But between Sweden’s light-touch approach and South Korea’s leave-nothing-to-chance policies, Johnson is leaning toward the latter. This seems to be born of the conviction that voters won’t tolerate the trade-off of losing lots of lives in exchange for getting back to work. Johnson’s own experience of Covid-19 will no doubt shape his thinking. There’s also a more pragmatic calculation that any new infection spike could deal the economy an even bigger blow.

Polls seem to bear out the prime minister’s caution. An Opinium poll for the Observer published last weekend showed that only 17% of people felt conditions were right for reopening schools. Only 9% thought it would be right to consider reopening pubs and even fewer said a return of sporting events or concerts should be allowed.

Yet support for the lockdown has been accompanied by a growing sense of public unhappiness with Johnson and his colleagues. The percentage of people who approve of the government’s management of the crisis has fallen to 47% from 61% three weeks ago. There will be little tolerance for more mistakes.

Having been tentative going into the lockdown, at such great cost, Johnson cannot now be anything but cautious in coming out of it. He’ll just have to find a way to make the new policy sound as straightforward and convincing as the one it replaces. He can’t afford to get the reopening wrong too.

Elaine He contributed a graphic to this piece.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Therese Raphael is a columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. She was editorial page editor of the Wall Street Journal Europe.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.