Lots of Restaurant and Entertainment Workers Need Lots of Help

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In 1918, when the last great pandemic swept through the U.S., professional cooks, dishwashers, waiters, waitresses, bartenders and their ilk made up about 1.4% percent of the nation’s workforce. That’s a guesstimate based on data from 1920, which I adjusted upward because Prohibition had taken effect that year, driving a lot of bars and surely some restaurants out of business. But it’s definitely in the ballpark: In 1910, their share of the workforce was 1.3%.

In 2019, the share of workers employed in what the Bureau of Labor Statistics now calls “Food preparation and serving related occupations” was 5.3%. That’s a big difference, and an indication of how the U.S. economy is in many ways more vulnerable now to damage from the “social distancing” measures needed to slow a pandemic than it was the last time they had to be used in a big way. Sure, lots of professionals can do their jobs from home using technologies that would have been inconceivable in 1918, but the share of economic activity and employment dependent on people gathering outside their homes — not just in restaurants and bars but also at theaters, stadiums, casinos, amusement parks, museums and such — is bigger too.

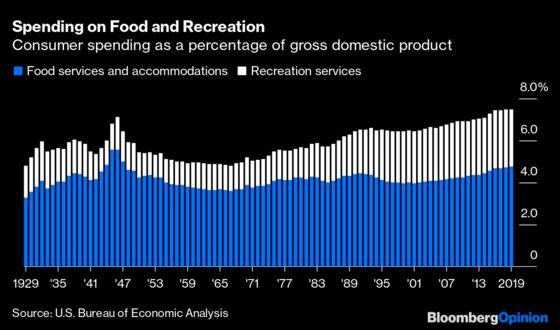

Here’s consumer spending on food services and recreation as a share of gross domestic product, numbers for which are available from the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Economic Analysis back to 1929.

A lot of people apparently went out to dinner in the waning days and aftermath of World War II! Also, suburbanization, the baby boom and the rise of television really do seem to have put a crimp on spending on restaurants and recreation in the 1950s and 1960s.

Since the mid-1960s such spending has been mostly growing as a percentage of GDP, with the recreation services share more than doubling since the late 1960s. Through the 1990s, recreation consumed remotely (what the BEA calls “audio-video, photographic, and information processing equipment services”) contributed a lot to this growth, but since then its share of GDP has held steady, with in-person entertainment and hospitality among the growth sectors of the slow-growth 2000s.

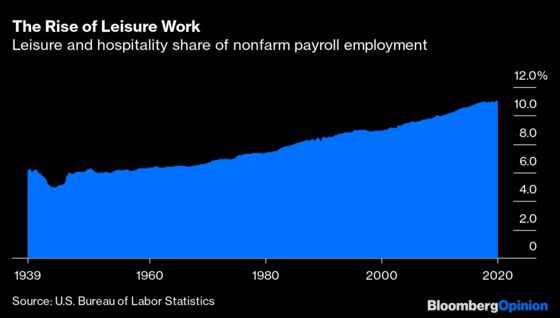

Because jobs in leisure and hospitality (I’m just following the terminology of the different statistical agencies here, with hospitality meaning accommodation and food services) generally haven’t been transformed or eliminated by technological progress — another way of saying that productivity growth in both sectors has been quite slow — their share of employment has grown faster than their share of GDP.

The 16.9 million leisure and hospitality workers in the U.S. account for 11% of all nonfarm payroll jobs. And the 5.2 million increase in employment in the sector since January 2000 amounts to almost a quarter of total job gains over that period. The pay isn’t great, with an average hourly wage of $16.87 in February versus $28.52 for the private sector as a whole. Neither are the benefits: Only 33.4% of leisure and hospitality workers had access to paid leave in 2017-2018, the lowest share of any major industry. Accommodation and food services workers in particular also seem kind of stuck: A recent analysis of 2018 job-switching data by Indeed Hiring Lab economist Nick Bunker found that they were among the least likely to switch to jobs in other industries.

All in all this paints a picture of a much-bigger-than-it-used-to-be and vulnerable group of workers who are about to be devastated by efforts to fight the coronavirus pandemic, unless the government in Washington comes through with some near-immediate aid. It’s not just them, of course — airlines, many brick-and-mortar retailers and other industries are being hammered too. But leisure and hospitality is really the epicenter here.

The 1918 influenza pandemic is not remembered for its economic disruption, at least not in the U.S. The economy fell into recession in August of that year, but the downturn was mild and brief and has since usually been attributed to the sharp decline in government spending at the end of World War I, not the flu. In a 2007 study for the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, economist Thomas A. Garrett did find evidence of sharp flu-related declines in business activity in autumn 1918 in several U.S. cities, so it’s possible that the pandemic played a bigger role in the downturn than it is credited for. But the Dow Jones Industrial Average did not have a particularly volatile 1918 and ended the year with a gain of 11%, which also seems better explained by the end of the war than by the influenza still raging in the winter of 1918-1919.

The pandemic of 2020, on the other hand, has already hammered the stock market, with a big economic hit now almost certain to come. The biggest difference from 1918, I think, is that this time we know what’s coming and what is causing it, which has led to a much sharper and more simultaneous reaction to the threat by governments, businesses and individuals. In 1918, the whole thing was something of a mystery, with the influenza virus that caused the pandemic not identified until 1940. Some cities in the U.S. did slow its spread by closing schools and banning large gatherings, but in general it proved unstoppable, killing an estimated 675,000 people here (0.7% of the population, or the equivalent of more than 2 million people today) and 17.4 million to 100 million worldwide (1% to 5.4% of the population, or the equivalent of 77 million to 419 million people today).

The social distancing measures being imposed by governments and adopted by individuals in the U.S. and around the world are meant to avert a disaster of that epic scale. Which makes sense! But the economies of the U.S. and other wealthy nations have grown quite dependent on the activities now being banned.

I couldn't separate leisure and hospitality as in the first chart because those numbers aren't available from before 1990.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.