What the Coronavirus Demands of the Fed

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- U.S. markets recovered somewhat on Monday as investors’ hopes brightened that there might be a coordinated response among the world’s central banks to the coronavirus outbreak. At the same time, there are warnings that there is little that the central banks can do to contain the economic damage.

The key to understanding this debate is whether Covid-19 creates more of a “supply shock” (a decrease in the capacity of businesses to make things) or a “demand shock” (a decline in the ability of consumers to buy things). The best answer is, both. And while the U.S. Federal Reserve may not be able to do much about a supply shock, it has the tools to fight a demand shock — if it is willing to use them.

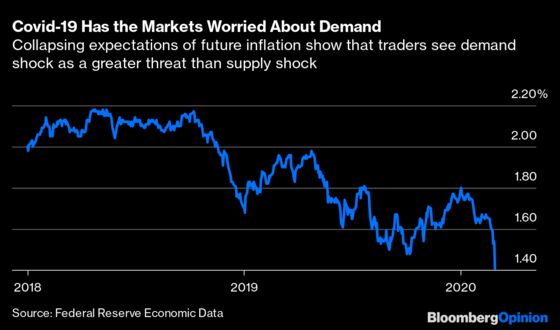

First, it is clear that the market convulsions in response to Covid-19 are mostly indicative of a demand shock. That is, investors believe that the virus will reduce the propensity of households and businesses to make purchases in the near term. Covid-19 has also disrupted supply chains, and will reduce the amount that businesses are able to sell. But if that were really what investors are worried about, then inflation expectations should be rising. Instead, they are collapsing.

Given such a strong demand shock, what can the Fed do? A coordinated fiscal response would be the best strategy, but that doesn’t mean that the Fed should stand idly by. Its most effective response would be to cut interest rates rapidly to zero — and then promise to hold them there until the economy has fully recovered and returned to its pre-coronavirus path.

The best measure of full recovery would be nominal GDP. Nominal GDP combines real growth with inflation. Using it as a target has the advantage of smoothing over the supply-shock effect from Covid-19: The Fed would allow higher inflation during the period when real growth was depressed, and as real growth recovered, it would seek to reduce the inflation rate.

Short of that, the Fed could modify some of the language that former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke used in the aftermath of the Great Recession, when he promised to keep rates at zero “for a considerable period of time after the economy strengthens.”

This time around, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell could promise to keep rates at zero “as long as Covid-19 remains a significant threat to global stability,” or some similar language. Such a statement would serve as a kind of automatic stabilizer. The worse conditions got, the longer the Fed would be expected to hold rates low. This alone would help avoid wild swings in financial markets as fears about the extent of Covid-19’s impact wax and wane.

This policy would not be without downsides. Like Bernanke’s promise, it would leave a lot open to interpretation. Markets did not know precisely how Bernanke defined a strong economy; in this case, they would not know what Powell would mean by a significant threat. That uncertainty would weaken the impact of the Fed’s policy. Still, a weak commitment is better than nothing.

If the Fed were unwilling to adopt either of these proposals, it could at least roll out Bernanke’s proposed average inflation target. That would mean making a commitment not to raise interest rates until the average inflation rate since the outbreak of Covid-19 rose to 2%. Such a commitment would mitigate a downward spiral and keep inflation expectations from collapsing, as they are currently.

Which if any of these measures the Fed chooses to take will determine how strong its response to the crisis will be. It is certainly within the bank’s power to provide a solid cushion to falling demand. The question is whether the Fed has the will to act.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Michael Newman at mnewman43@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Karl W. Smith, a former assistant professor of economics at the University of North Carolina and founder of the blog Modeled Behavior, is vice president for federal policy at the Tax Foundation.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.