Returning to Business Is Going to Take a Pay Raise

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- America’s top executives are warning of “economic catastrophe” if workers don’t return in May, according to Axios. Several of them told the media company that “they want to have a hard national conversation about trade-offs involved in any widespread lockdowns beyond the middle of next month.”

That conversation needs to include a general increase in wages, probably not a subject the CEOs want to talk about. America’s biggest companies and their CEOs have feasted on low-wage labor for years, even as evidence mounted that workers failed to make ends meet. It’s not that companies couldn’t afford to pay workers a living wage. Indeed, America’s biggest companies have enjoyed record profitability in recent years, and the CEO-to-worker pay ratio has swelled to more than 300 to 1, an obscene spread when many workers struggle to afford housing, health care, child care and other basic necessities.

Simply put, corporate executives valued fattening their coffers more than looking after workers. So they hid behind shareholder primacy, the idea that enriching shareholders is their highest priority. They complained that unilaterally raising wages would put them at a competitive disadvantage, even as they fought efforts to raise the minimum wage. They even blamed the market: If it decrees that workers should receive inadequate wages, who are they to second-guess it?

Any competent observer could see that the status quo was unsustainable. After all, the whole point of work is to make a living. If employers were unwilling to uphold their end of the bargain, what could they expect from workers in return? Some CEOs recently came to that realization, or said they did. The Business Roundtable, an association of top American CEOs, adopted a new “Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation” in August signed by 181 CEOs committing to “lead their companies for the benefit of all stakeholders,” including workers. Days later, Business for Inclusive Growth, a coalition of 34 multinational companies, unveiled an initiative to tackle inequality at the Group of 7 summit.

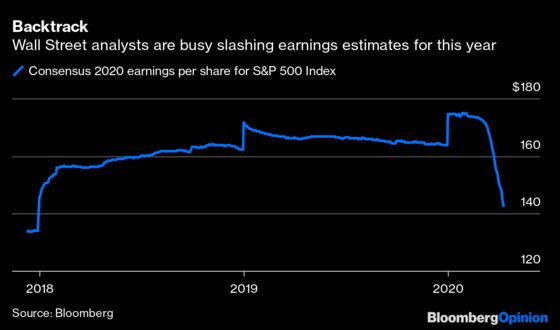

Companies were slow to act, however, and now time is short. The complaints by CEOs are a last-ditch effort to avert two conflicting situations. The first is a severe earnings recession. Public companies have begun reporting first-quarter earnings this week, and it won’t be pretty. Wall Street analysts have already slashed their 2020 earnings estimate for the S&P 500 Index to $142 a share from $175 when the year began. And that assumes business will return to normal in short order. If it takes companies longer to wrangle workers, earnings are likely to take a deeper dive.

The second is a spike in wages. The coronavirus has laid bare that without workers to produce and consume their products, even the most formidable companies are just empty shells. The problem is that unless companies sweeten the deal, workers may not be so eager to return. After years of beaten-down wages and growing pay disparity, workers have far less to lose than their bosses. The federal government and central bankers have also conceded that they will have to spend whatever it takes to keep Americans fed and housed, so workers may reasonably decide that government assistance is preferable to flirting with the virus until reliable treatment or a vaccine is available.

That’s particularly true for the two sectors in the crosshairs of this crisis. One is consumer discretionary, which includes travel, entertainment and retail. Workers in that sector will arguably be most at risk when consumers decide it’s safe to leave the house again. They are also the most poorly compensated. My Bloomberg colleague Jenn Zhao compiles the median employee compensation for the biggest U.S. public companies by market value. The average across 76 consumer discretionary companies was roughly $33,000 in 2019, which is the lowest of the 11 sectors and half the amount realistically needed to raise a family of four in the cheapest places in America.

The other sector is consumer staples, which includes essentials such as food, beverage and personal products. Workers in that sector are perhaps the most urgently needed, and yet the second most poorly paid. The average compensation among 41 consumer staples companies was roughly $45,000 last year.

If business is to resume any time soon, companies and workers will have to work together to manage the grave risks ahead, as little remains known about the virus. But collaboration requires trust, which is in short supply thanks to companies’ long-running neglect of workers. According to Gallup’s most recent survey of the public’s perception of honesty and ethical standards among the professions, just 20 percent of respondents gave business executives a rating of “very high” or “high.”

CEOs ought to realize that no amount of fear-mongering about the economy is likely to hasten business as usual. I wrote last year that if companies wouldn’t raise pay, the government would make them. Coronavirus beat legislators to it. Absent a quick end to the fight against Covid-19, if CEOs want to avoid a severe earnings slump, they should consider paying workers a living wage.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.