Virus Recession Gives Economists a Shot at Redemption

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Macroeconomists famously mishandled the crisis of 2008. Their models mostly excluded the financial sector, making it difficult to foresee the possibility of a crisis like the one that happened. In the aftermath, some argued heavily against fiscal stimulus, blunting countries’ ability to respond effectively. And some warned of inflation that never even came close to materializing.

But with the coming of the coronavirus depression, macroeconomists have a golden opportunity to redeem themselves. Shutdowns have given theorists some time to think about what’s coming. This downturn is going to be bigger and more complicated than the last one, which only increases the need for theories to anticipate some of the potential scenarios.

Traditionally, many macroeconomists tend to think in terms of a simple model of aggregate demand and aggregate supply. In this basic framework, there are two kinds of recessions. The first is caused by demand shocks, in which consumers decide to hoard their money instead of going shopping. The second is caused by supply shocks, in which producers find it more expensive to produce.

Recessions in the last century generally fell into one of these two categories. The Great Recession and the Great Depression were both caused by huge financial crises, and displayed all the hallmarks of demand shortages -- in particular, falling prices. In contrast, the oil crises of the 1970s were fairly obviously a supply shock, causing inflation and stagnation at once.

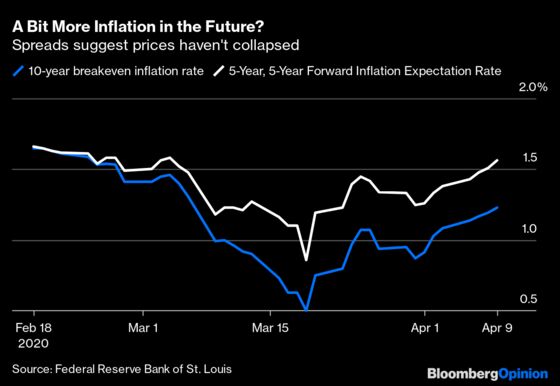

But it’s not yet clear whether the coronavirus shutdowns will look like either of these textbook examples. Price changes are usually the way economists tell the difference. During the acute phase of the crisis, when shutdowns were beginning, inflation expectations fell, which looks like a demand shock. But they bounced back quickly:

Interestingly, the first macroeconomic models to tackle the shutdown predict exactly this sort of ambiguous effect on inflation. A new paper by economists Veronica Guerrieri, Guido Lorenzoni, Ludwig Straub and Ivan Werning tries to model an economy where some industries closed down while others stay open. Realistically, they assume that workers from the former sectors can’t just go to work in the latter. A supply shock in the shutdown sectors thus turns into a demand shock for everyone else, and prices can move in either direction.

What can the government due to stabilize the situation in such a world? Relying on standard epidemiological models, the economists conclude that shutdowns are indeed the optimal policy in the short term. Economic relief spending is important, but it fails to have its traditional Keynesian stimulative effect because consumers can’t spend their checks on businesses that are shut down; thus, the economists recommend that monetary policy be used to keep businesses afloat.

This provides theoretical backing for most of the measures in the recent $2 trillion relief bill, as well as some additional steps. It implies that the government’s emergency loans to businesses are crucial. And it also suggests that paying companies to keep workers on payroll and putting cash directly in people’s pockets can sustain aggregate demand.

The goal of these short-run measures is actually twofold: first, to allow people to survive the shutdowns comfortably and second, to try and restart the economy as quickly as possible after shutdowns are lifted. The ideal scenario is one in which the shutdowns are just like turning the economy off and on again: In this pleasant fantasy, when the virus has been suppressed with testing regimes and other public-health measures, people would just go back to shopping at the same stores, eating at the same restaurants and working in the same offices. The economy would then bounce back to where it had been.

Unfortunately, that is not going to happen. It’s a good goal to strive for, which is why payroll preservation measures, emergency loans and the like are so important. But the epidemic will undoubtedly change the economy in enduring ways. Consumption habits will shift, as will patterns of global trade. This means lots of business models that worked perfectly well before coronavirus will be unviable after. The large number of workers who have lost their jobs -- some economists are forecasting an unemployment rate of 13% or more -- will have to be reintegrated into the workforce. And financial institutions will find that some of the corporate debt they own will no longer be good.

So macroeconomists need to figure out what this will mean for the next five or 10 years, after shutdowns are lifted. After reopening, it’s not clear whether the biggest factors weighing down the economy will be supply-based or demand-based. Financial weakness and a backlog of unemployed workers will tend to depress demand. But a contraction in global trade will crimp supply as well; cutting off cheap foreign supply chains might be a bit like cutting off oil. The shutdowns themselves might also look like a supply shock, because they make it harder to source goods and services.

And of course, it’s possible that these supply and demand shocks will interact with each other in a few years in a different way than they might in the short term. To properly predict how the coronavirus recession will play out, macroeconomists will need to take into account many factors -- labor market disruptions, the financial sector and international trade.

Which means they need to get started now.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.