(Bloomberg Opinion) -- When it comes to the U.S. stock market, this is not yet the historic buying opportunity some investors have been waiting for.

Contrary to their reputation for weak stomachs, ordinary investors appear to be hanging on to their stocks, judging by the chatter online and continuing net positive flows to exchange-traded funds favored by long-term stock investors. But after a brutal sell-off that has carved 30% off the S&P 500 Index since its record high on Feb. 19 through Monday, many investors are no doubt wondering whether U.S. equities are a bargain now.

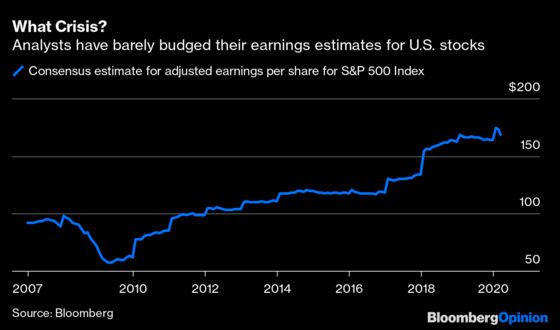

The short answer is no, even after all the recent turbulence, although it’s easy to conclude otherwise. Wall Street loves to parade its favorite stock market barometer, the price-to-earnings ratio based on analysts’ forward earnings estimates. Ever the optimists, analysts have slashed their earnings expectations for this year by just 3% since Feb. 19, a laughably modest haircut against the backdrop of a U.S. economy widely expected to contract because of coronavirus-related complications and a Federal Reserve desperate to temper the damage with its historic intervention on Sunday.

Here’s the rosy math: Analysts expect earnings of $169 a share for the S&P 500 this year, down from $174. That translates into a forward P/E ratio of 14, which is not terribly far from the 2008 financial crisis-era low of 11. But how realistic is that earnings estimate? It’s reasonable to suspect that the economic contraction from the coronavirus might rival the one that followed the dot-com bust in 2001, or even the one around the financial crisis. Earnings declined by 54% and 92%, respectively, from peak to trough during those two episodes.

But let’s assume analysts ultimately write down earnings by 30%, which is an average of the two write-downs they were eventually forced to make during the previous two downturns. That would yield earnings of just $122 a share and a forward P/E ratio of 20, which leaves a lot more room for the market to tumble further.

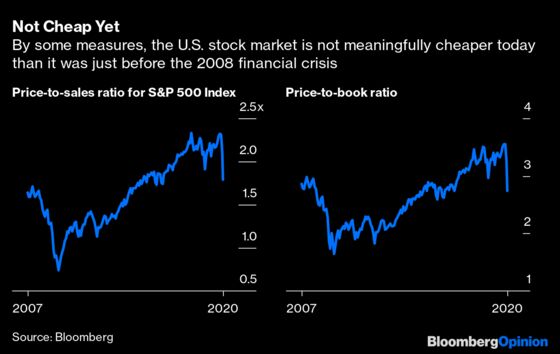

One need not argue about earnings to see that the market is not yet a bargain. Based on its price-to-sales ratio, the S&P 500 is still roughly 50% more expensive than its dot-com low and 160% pricier than its financial crisis low. It’s also more expensive based on other measures, such as price-to-book and price-to-cash flow.

The fact that many investors are surprised the market is not cheaper, by historical standards at least, shows how accustomed they’ve become to lofty stock prices. By some measures, the bull market that just ended was the second longest on record. There was also a lot of talk along the way that the growing availability of low-cost index funds meant that investors are willing to pay more for stocks than they once were.

It’s true that average valuations for U.S. stocks have risen in recent decades, but that may be false comfort. For one, over the same time, average valuations have declined in many other developed countries where index funds are as popular and widely available, which may mean that the recent trend in the U.S. is a fluke. More important, there’s no evidence that U.S. stock valuations are any higher during periods of stress, which is ultimately what investors care about when attempting to gauge how much further stocks might fall.

In fact, the bottom is uniquely too far for comfort in the U.S. Broad U.S. stock market gauges are stuffed with large-cap growth stocks, many of which were extravagantly expensive before this sell-off began, such as Amazon.com Inc., Tesla Inc., NVIDIA Corp., Netflix Inc. and many others. When those stocks are excluded, U.S. stock valuations appear much closer to previous bottoms. And bona fide bargains abound outside the U.S. where stock markets have been beaten up for years. Overseas value stocks, for example, are already at or near their financial crisis lows.

None of this means U.S. stocks are necessarily heading lower, of course. And even if they do, attempting to time the exit and re-entry is famously difficult. But for those wondering how much more room the U.S. stock market has to fall, the answer is a lot more than investors probably realize.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.