(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Over the more than 100 years that luxury retailer Neiman Marcus has been in business, it’s quite likely some customers who shopped there were living beyond their means. A similar state afflicted the department store on Thursday, as it filed for bankrupty, overwhelmed by its billions of debt.

With its filing, Neiman Marcus became the first major department store to succumb to bankruptcy amid the coronavirus pandemic, and the second retailer to do so this week after J. Crew filed for protection from creditors on Monday. The Chapter 11 process enables Neiman Marcus to shed about $4 billion of its existing borrowings. Less burdened by its debt, it will be able to slim its estate as needed and invest in the remaining stores as well as its online platform to better compete with the big fashion houses and e-commerce rivals. Even so, it faces challenges thriving in a transformed luxury landscape rocked by deep economic shocks, at a time when brick-and-mortar retailers have the additional burden of reopening while mitigating health risks.

Neiman Marcus for decades was one of the few places where wealthy Americans could buy clothing, jewelry and the extravagant holiday gifts featured in its seasonal catalog. As such, it occupied a distinct position in the retail industry, sitting above more mid-market rivals such as Macy’s Inc. But a confluence of industry pressures — compounded by the lengthy Covid-19 shutdown as well as debt from its $6 billion buyout 2013 by Ares Management LLC and the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board — undermined the department store that began life in Dallas in 1907.

When Herbert Marcus, his sister Carrie Marcus Neiman and her husband A.L. Neiman set out to fashionably dress the community, there weren’t a lot of options. As with London’s Selfridges, shoppers flocked to this shrine to the new consumerism. One of Neiman’s strengths was having a range of designer brands under one roof. To underline its fashion credentials, in 1938, Stanley Marcus, the oldest of the four Marcus sons, established an award for designers, with Coco Chanel and Yves Saint Laurent among its recipients. Today, the picture couldn’t be more different.

Over the past decade or so, the big fashion houses have become less reliant on department stores such as Neiman. Wanting to take more control over their image, and concerned about their handbags and shoes being discounted, they moved to establish their own retail networks, with spectacular flagships. Then there is the rise of selling luxury goods online. In the early days of the internet it seemed inconceivable that men and women would buy everything from a Cartier watch to a Bottega Veneta handbag online. But that’s just what the likes of Richemont’s Net-a-Porter, have achieved. The luxury houses, such as Kering SA’s Gucci, have also been developing their own online presence, adding even more completion.

Neiman is no laggard here itself, generating about 30% of its sales from online, and also owning e-commerce platform MyTheresa (which won’t be included in the Chapter 11 process). But this hasn’t brought in as many younger customers as might be expected. As with other storied retailers, its customers are ageing. While many older Americans have plenty of money to spend, they often prioritize other areas, such as dining out or travel — at least they did before Covid-19 — over spending on things. Meanwhile, the under-35 crowd accounted for all the growth in the luxury industry in 2019, according to Bain & Co.

To tap into this demographic, Neiman needs to be more innovative and inclusive. Rival Nordstrom Inc. has done a good job here, from embracing less pricey designers to experimenting with smaller, neighborhood stores. These locations may be even more appealing to shoppers in a post-Covid world.

Bringing in edgier designers, or those with cheaper price points, would be another option. This doesn’t mean mass market. But it could take a leaf out of London’s Selfridges. As well as Chanel bags costing thousands of dollars, and watches costing hundreds of thousands, it also offers more affordable clothing and accessories, such as Kurt Geiger shoes. All that helps to make the store more approachable. Collaborations to create exclusive collections and pop-up stores with quirky brands are other possibilities.

All these actions take significant investment. And that’s not easy with a big debt burden. With that lessened, the group should have more scope to meet the required outlay. And of course, there may be stores that either need closing, or shrinking. Nordstrom said recently that it would permanently close 16 of its locations. Neiman is already closing most of its outlet stores.

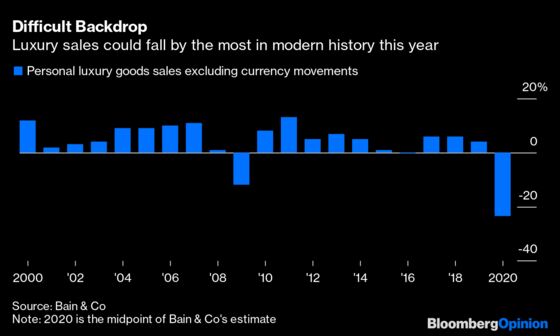

The path to recovery won’t be straightforward. Not only does it have the challenge of reopening stores, but the luxury goods market is facing the worst year in its history. Meanwhile, amid a tougher market, the fashion houses may be even choosier about where they allow their products to be sold.

A rival group of creditors was urging Neiman to put itself up for sale. So it is still possible a buyer may come forward. If either can breathe fresh life into the historic department store, there is a viable retail business.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andrea Felsted is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the consumer and retail industries. She previously worked at the Financial Times.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.