Coronavirus Might Make Americans Miss Big Government

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In South Korea, the number of people who are confirmed to have been infected with Covid-19, the pandemic disease commonly known as coronavirus, has ballooned to over 5000 as of the time of this writing and will certainly continue to rise. In the U.S. the official number infected is only 118. But much of this difference may be an illusion, due to differences in how many people are getting tested. South Korea has made a concerted effort to identify all the people infected with the virus, creating drive-through testing stations. The U.S.’ testing efforts, in contrast, look almost comically bungled.

The list of ways that U.S. institutions have fumbled the crisis reads like something out of a TV comedy: The number of test kits issued in the U.S. has been a tiny fraction of the number issued in South Korea. An early testing kit from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) contained a faulty ingredient and had to be withdrawn. Regulatory hurdles have slowed the rollout of tests, with officials from the CDC and the Food and Drug Administration only now discussing what to do. There are stories of possible coronavirus patients being denied testing due to maddeningly strict CDC limits on who can get a test. Some cities may have to wait weeks for tests to become widely available, during which time the populace will be left in the dark. Worst of all, the CDC has now stopped disclosing the number of people being tested, a move that seems likely to spread panic while reducing awareness.

What are the reasons for this institutional breakdown? It’s tempting to blame politics – President Donald Trump is obviously mainly concerned with the health of the stock market, and conservative media outlets have worked to downplay the threat. But the failures of the U.S.’ coronavirus response happened far too quickly to lay most of the blame at the feet of the administration. Instead, it points to long-term decay in the quality of the country’s bureaucracy.

Political scientist Francis Fukuyama has been sounding the alarm about the weakening of our bureaucracy for years now. He notes that the civil service has always been less powerful in the U.S. than in other advanced nations in Europe and East Asia, as the U.S. relies more on the courts. That may lend an imprimatur of fairness to government decisions, but courts are obviously ill-equipped to handle acute threats like pandemics. Fukuyama also points out that less bureaucratic power means more direct political control, which allows the wishes of civil servants to be overridden by the desires of lobbyists. All of these tendencies, he argues, have become worse in recent decades.

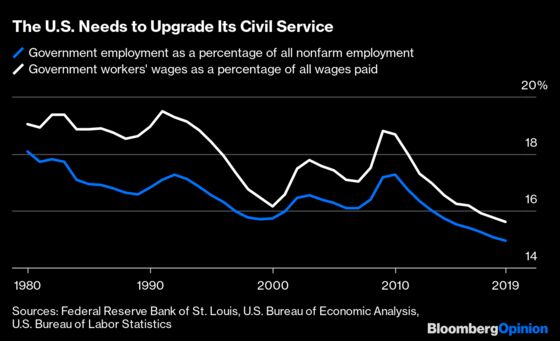

A decline in institutional competence is hard to measure. But the amount of resources that the U.S. as a whole devotes to its bureaucracy is shrinking, in terms of both wages and number of employees:

Very little of this decline is a function of our shrinking military. The civilian federal workforce is a much bigger factor, having fallen from about 4% of GDP in 1970 to under 2% today. Much of the work is now handled by contractors, or not done at all. State government cutbacks have also been big.

A bureaucracy whose size doesn’t grow in step with the overall economy means that civil service is not a promising career for young college graduates. Inflexible government pay structures also make it hard to reward excellence or get ahead. Salaries are uncompetitive at the top end, topping out at just under $200,000 for the most highly-paid senior bureaucrats -- only slightly more than an entry-level engineer makes at Google.

Part of the problem is that it’s very difficult for the U.S. to compete with the private sector when the latter is so efficient. But that’s not true everywhere: Singapore manages to have a thriving private sector alongside a highly effective bureaucracy that recruits the best and brightest. So it’s largely a question of political will.

In the U.S. the public sector has come under sustained attack from the political right for many years. President Ronald Reagan famously declared that “government is the problem,” while anti-tax activist Grover Norquist stated that he wanted to “drown [government] in a bathtub.” Republican and Democratic presidents alike have enacted pay freezes for federal workers.

Trump is continuing the assault on the civil service, proposing yet another pay freeze. In 2018 he fired an executive branch team responsible for responding to pandemics and attempted to decrease funding for public health.

Economists, meanwhile, have been little help. The discipline focuses almost exclusively on incentives and markets, neglecting the details of building efficient government organizations. It’s therefore little surprise that the policy establishment and commentariat, whose ideas are deeply influenced by economics, tends to treat the civil service as an invisible black box and focus instead on the details of regulation and taxes.

Over time, all this neglect and hostility adds up, reducing the flow of talent into the civil service and hampering agencies’ effectiveness by creating uncertainty about future hiring and budgets. Poor responses to pandemics and natural disasters are only one bad result -- expensive and decaying infrastructure is another.

Countries need efficient, talented, thriving bureaucracies. The U.S. is no exception. If the decline of the civil service isn’t reversed, the coronavirus epidemic will not be the last disaster that the U.S. finds itself unprepared to handle.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Nicole Torres at ntorres51@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.