(Bloomberg Opinion) -- After bringing everything to a screeching halt in an all-out war against the coronavirus, French President Emmanuel Macron wants to get the economy going again. The dark draconian days of the Covid-19 lockdown are over, confirmed cases have continued to fall, and Monday marks a new roll-back of stay-at-home curbs as cinemas, museums and more schools reopen.

To do so, he’s harking back to themes from his 2017 presidential campaign as a pro-jobs candidate who would be judged on his ability to shake up the country’s rigid labor market and complex pensions system.“France must fully get back to work,” he said in a national televised speech on June 14. “We must work, and produce, more.”

These challenges aren’t unique to France, or Europe, but few other countries had seen an exhausting cycle of social unrest and anti-government protests in the period leading up to the virus, which contributed to Macron’s approval rating stagnating at 38%.

Labor unions pounced on his words after his TV speech, accusing him of wanting to make up for lost economic time by forcing people to work longer — exactly what fueled protests against his now-suspended attempt at pension reform. Newspaper Liberation superimposed Macron’s features onto the head of Nicolas Sarkozy, a center-right predecessor whose mantra in 2007 was: “Work more to earn more.”

It’s hard to rally the troops after creating a world without work. The sudden return of the office in people’s minds is triggering stress: Some 42% of workers are in psychological distress, workplace consultancy Empreinte Humaine estimates. While not always unwarranted, every excuse for not returning to work is being given, from childcare burdens to the fear of taking public transport again, and doctors report a steady flow of people asking for sick leave.

It’s no wonder Macron made school mandatory again: As of June, 40% of teachers were not in the classroom, with remote teaching adding to parents’ logistical nightmares. Some white-collar workers paid to stay at home have gotten comfortable with this new parallel reality. “At first, I felt guilty for not working,” one furloughed staffer told me. “Then it went away.”

In an ideal world, reopening the economy would bring all of these workers back online. But the French economy still bears the scars of one of Europe’s strictest lockdowns, which crushed the tourism industry and gummed up factory production and supply chains. According to pollster Ifop, the population was divided neatly into three: 34% working on the front lines (from medical professionals to grocery store employees), 30% working from home, and 36% not working at all. It’s the latter that represent the biggest policy challenge.

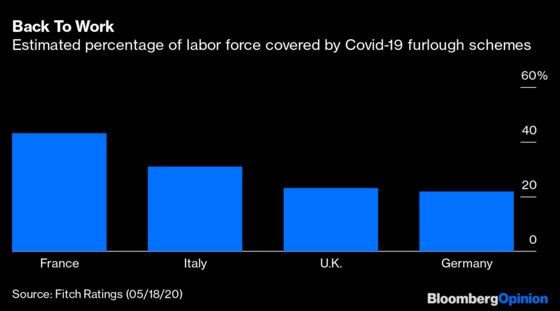

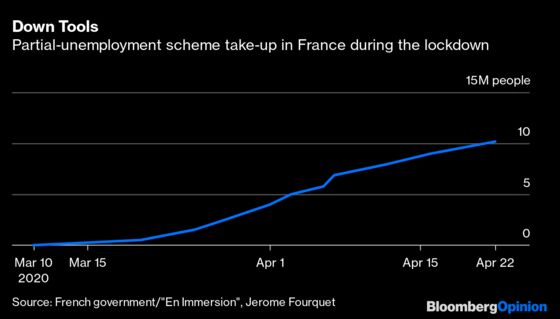

To avoid mass layoffs, the Macron administration — rightly — rolled out one of the most generous furlough schemes in Europe, with the state taking on the payment of as much as 80% of gross wages. Companies forced to close could preserve jobs and avoid the hassle of rehiring people later. The program covered almost half the French workforce, according to Fitch Ratings. That compares with around one-third of workers in Italy, and around one-fifth in the U.K. and Germany.

But paring back this 17 billion-euro ($19 billion) lifeline is proving very hard indeed.

Companies are in no fit state to reabsorb France’s entire army of furloughed workers. The virus is still with us, and so is social distancing, meaning the cost of doing business has gone up even as demand has gone down. While helping firms, generous state support such as guaranteed loans has also made them more indebted and less likely to hire or spend. Some 68% of companies have either delayed or plan to delay investment, according to research firm Rexecode. Anxious bosses are pulling all levers at their disposal to keep up workplace productivity, but the aerospace and automobile sectors are examples of industries where furloughs will last. There’s no point in kicking a valuable economic crutch out of the way if the alternative is more job cuts.

The risk of funneling indefinite subsidies into the economy is that you end up wasting taxpayer money on “zombie” jobs that may never be viable, argues economist Patrick Artus of Natixis SA. [It may be better to focus] on struggling sectors and offer smaller, but more direct, wage subsidies. Fiscal stimulus could then be targeted at more in productive areas like the green economy, creating new jobs and helping to retrain manufacturing workers.

There’s a chance here for Macron to hand more decision-making to local authorities and to companies themselves, which have been striking special agreements with staff to reduce wages. One example of this, consultancy Technologia says, is an aerospace firm that agreed pay cuts to avoid 700 potential layoffs.

For now, it looks like the return to work will be a gradual affair. Covid-19 is still with us, and government subsidies will be too. In the meantime, workers will be tempted to resist the calls for working harder, much like the 2004 book “Bonjour Laziness” by Corinne Maier that advocated a “disengagement” from corporate life. And Macron will likely have to change his tune once more to be heard.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Lionel Laurent is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Brussels. He previously worked at Reuters and Forbes.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.