Landlords Shouldn’t Get Away Without a Hit This Time

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The question of who takes the hit from coronavirus is implicit in many of the policy decisions that governments will make during the next few months. There are basically two criteria leaders should use to decide who loses the most from coronavirus. The first is human welfare -- making sure that everyone still has food, shelter and the other necessities of life, not just during the pandemic but after it. The second is productivity; the government needs to preserve the ability of companies and workers to create real economic value. Both considerations suggest that landlords should take a hit.

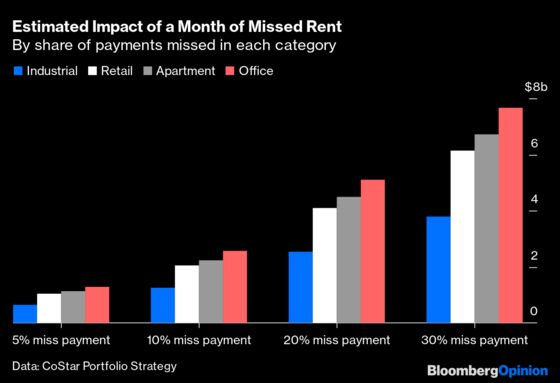

With many businesses shuttered and workers out of work, the country is experiencing a deluge of missed rent payments. On the residential side, fewer than 70% of renters made payments by April 5; normally more than 80% of payments are on time. Even one month of missed rents can result in large losses to landlords:

In Europe, where lockdowns have been more severe, the crisis may be even more acute.

Governments ultimately must decide how much of these rent payments will be collectable after the crisis ends and how much will have to be written off by the landlords. In the U.S., various states and cities have suspended evictions. Landlords report that many governments are refusing to enforce rent collection during the crisis. There will undoubtedly be a long legal tussle over unpaid rent for years to come. Meanwhile, there is a patchwork of government policies aimed at making landlords whole. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have granted mortgage relief to landlords who suspend evictions. The Paycheck Protection Program will bail out some landlords and increased unemployment insurance will allow many tenants to keep paying rent.

The question of who is ultimately responsible for missed rent is therefore still very much up in the air. The worst option would be to force tenants to spend the next few years paying back months of rent that they were unable they missed through no fault of their own. This would be unfair, and it would punish those who can least afford to take the hit. It might be a recipe for social unrest. Large-scale rent relief is necessary, whether through enforced forbearance or government handouts to renters.

The next question is how big a loss landlords should take and how much should be borne by taxpayer. If property companies fail, banks that lend to these companies will have to write off billions of dollars in loans. That could weaken the financial system, worsening and prolonging the depression. But the government could avert this by bailing out the banks and letting property companies simply fold. This would mean that land, as an asset class, would take the hit.

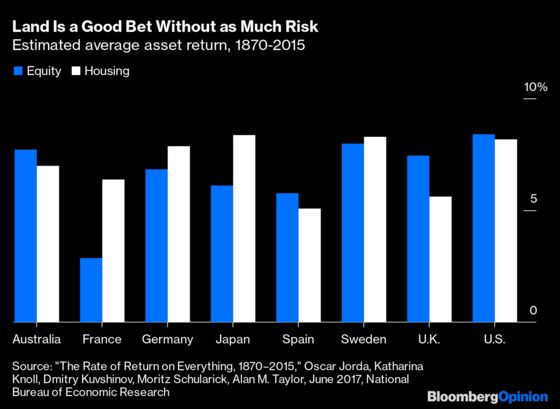

One argument for doing this is simply that it rarely happens. Researchers have found that since the mid-19th century, housing has yielded similar returns to equities in most developed nations while incurring much less risk.

In an efficient financial market, this shouldn’t happen; risk and reward should be proportional. One possibility is that government policy consistently intercedes on behalf of landowners -- rebuilding after disasters and wars or setting zoning policies so that land usually or always appreciates. In other words, government backing can turn land into a lucrative one-way bet.

Not only is that unfair, it could be a big contributor to inequality. In a 2016 paper, macroeconomist Matthew Rognlie found that most of the increase in capital’s share of national income documented by economists such as Thomas Piketty was because of rising land prices, not to the increasing value of corporations.

This could also be bad for national productivity. As 19th century economist Henry George pointed out -- and as subsequent generations of economists have reaffirmed -- landlords naturally receive more value than they produce. Only an ideologue would believe that landlords are parasitic; they obviously produce value by building, upgrading and maintaining properties. But because the value of the land they own is determined by the productivity of the city around that land, much of the rent that landlords capture is not generated through their own efforts. That makes it inefficiently expensive to live in urban areas even in good times; in a crisis, it can deal a lasting blow to the livability of highly productive cities.

Letting landlords take a hit from coronavirus, as long as it doesn’t hurt banks, could therefore be the optimal policy. (Small unincorporated landlords might be exempted from these losses, perhaps with a targeted bailout.) It would represent a rare loss for a class of wealthy people who are used to not taking losses. The alternative -- bailing out landlords at taxpayer expense -- might seem easier, especially in a time when bailouts in plentiful supply. But it’s probably not the fairest or most productive approach.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.