(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Like it or not, we may have to submit to the intrusion of big data because of the coronavirus.

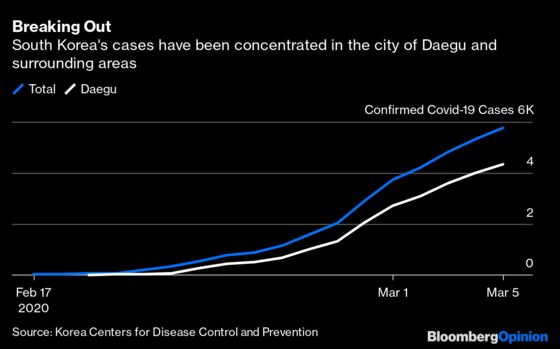

South Korea is at the cutting edge of how this could work in a democracy. Tracking down patient zeros — the first documented cases — and the ones that follow is becoming critical to containment and public safety. There won’t be a cure or vaccine anytime soon. The global number of cases is nearing 100,000. South Korea has the largest outbreak outside China, with almost 6,000 cases. The surge has largely been contained to the city where it erupted, Daegu, around a religious cult.

Central to South Korea’s approach has been the extensive collection and effective use of data as a public good – in this case, disease surveillance and testing. The Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s daily reporting details patients affected and being tested, connections between them and what provinces they’re in. It includes fatality rates by age and gender. Health authorities posted a detailed log of patients’ whereabouts prior to confirmation of infection. Their names weren’t given, but they were numbered. People were informed that this personal information was being collected and publicized. They didn’t have a choice.

A Wall Street Journal report chronicled this: “Patient No. 12 had booked seats E13 and E14 for a 5:30 p.m. showing of the South Korean film, “The Man Standing Next.” Before grabbing a 12:40 p.m. train, patient No. 17 dined at a soft-tofu restaurant in Seoul. Patient No. 21 drove her car to attend a weekday evening church service.”

From a visit to a funeral home to a restaurant and bakery, a website that uses government data now allows tracing infected individuals. Color-coded by timing, it allows people to avoid those places and enables so-called social distancing, or staying away from large groups and crowds. It’s a more focused way to confront the epidemic than living in a generalized state of paranoia. And far more targeted than locking down entire cities. App developers are using the public data to warn users if an infected person is within 100 meters. Because the coronavirus has been asymptomatic in some cases, tracing those infected is even more important.

Tech giants have mined data this way in marketing for at least a decade. Scientists have analyzed data from Twitter Inc. and Alphabet Inc.’s Google Trends to understand human mobility. Cellphone data has been used to track cholera outbreaks and the role of crowds. South Korea is pulling all these threads together. It’s also collecting data from pharmacies and doctors on how medication is being dispensed, and plans to use a similar system to ensure people aren’t hoarding masks.

The more information you have, the more you can do with it. South Korea’s growing pile of data has enabled authorities to quickly test for the disease and keep pace with its rapid spread. Knowing that the cases are concentrated in Daegu has helped ramp up testing there. That’s a big step forward. In previous outbreaks, delays in collecting and tracking led to slow response times.

This capacity hasn’t been conjured from nothing. South Korea has spent years investing in technology and, more recently, biotechnology. Research and development spending accounts for around 4.5% of gross domestic product, topping the list of countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, which average around 2.37%. Given the out-sized role of companies like Samsung Electronics Co. and SK Hynix Inc. in the country’s life, South Koreans are highly tech-enabled, with nine out of 10 people on the internet and 95% using smartphones.

To be sure, disease surveillance isn’t new. Typically, healthcare professionals need to inform public health officials for selected diseases. That takes time. Voluntary sharing risks misreporting, with no validation from lab tests. There are other pitfalls, especially data collection based on human behavior and media coverage. For instance, Google and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention teamed up for web data on searches around the flu. In 2013, Google’s estimates for Christmas-time flu peak were almost double the CDC’s. Meanwhile, Google underestimated swine flu.

Putting data to work effectively isn’t an easy task. In China, a highly connected and watched society, fears of misuse and mass-scale surveillance abound. Beijing has resorted to data to track citizens in the ongoing quarantines across the country. The U.S. doesn’t seem to have the data, or at least isn’t marshaling it effectively. Much of what it collects is in the hands of Big Tech. Testing and reporting for the coronavirus is proving difficult (and almost non-existent in places). In Europe, even if governments wanted to fully utilize all available information, new privacy laws would get in the way.

South Korea is conscious of risks to privacy; there are laws to protect data about children and personal information. But having a watchful eye in the name of public health has helped in this time of crisis. Without using data as ammunition, it isn’t clear how to effectively contain the spread of this disease without locking down large parts of a country.

So, wouldn’t you rather know if someone with coronavirus had been sitting where you’re now sipping coffee?

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Patrick McDowell at pmcdowell10@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Anjani Trivedi is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies in Asia. She previously worked for the Wall Street Journal.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.