(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Even as some retailers begin to open stores again, the pain across malls and main streets continues to take its toll.

J. Crew Group Inc. on Monday said it would begin pre-arranged Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings and enter into a $1.65 billion debt-for-equity swap with its lenders, becoming the first major U.S. retailer to succumb to the economic convulsions caused by the coronavirus pandemic. It won’t be the only casualty.

Other chains are grappling with the same issues: heavy debt loads, compounded by the damage done from locations closed for weeks. Neiman Marcus Group Inc. is closing in on a bankruptcy deal with a group of lenders, Bloomberg News reported on Monday, citing people with knowledge of the matter, and J.C. Penney Co. is reportedly in talks on a loan that would fund it through a restructuring. Meanwhile, Victoria’s Secret-owner L Brands Inc. said late Monday that it agreed to terminate plans to sell a majority stake in the lingerie chain to private equity firm Sycamore Partners. Jefferies analyst Randal Konik had warned last month of potential medium-term solvency issues at L Brands after Sycamore sued to get out of the transaction, citing a collapse in sales and looming debt maturities.

Every brand has its own story. In the case of J. Crew, it was one of the first mainstream U.S. retailers to gain real traction with the fashion crowd, and in its heyday was also ahead of its time in areas such as store design. The leadership of former chief executive Mickey Drexler and creative director Jenna Lyons took its preppy styles from classic to cutting edge, all helped by the brand being a favorite of Michelle Obama. But its trendy designs eventually alienated some customers, and when the power partnership came to an end in 2017, it never regained its stride. With cheaper competitors such as Inditex’s Zara and a resurgent Ralph Lauren Corp at the top end, J. Crew had to rely on incessant discounting.

J. Crew had hoped in recent months to spin off its faster-growing, denim-focused Madewell arm as it sought to cut borrowings of almost $1.7 billion as of February. But plans for the initial public offering were scuppered by the pandemic, and it was left struggling to deal with its debt, a legacy from its 2011 leveraged buyout by TPG Capital LP and Leonard Green & Partners LP.

Neiman Marcus, meanwhile, was acquired in a $6 billion leveraged buyout by Ares Management LLC and the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board almost six years ago. The chain has been in a race with its luxury rivals, such as Nordstrom Inc. to turn stores into temples of indulgence. That all takes investment, made harder with a debt load of $4.3 billion, according to Bloomberg News. J.C. Penney is at the other extreme. It must deal with shabby stores as it struggles to stay relevant while managing total borrowings of $3.6 billion excluding store leases as of Feb. 1.

All three chains are facing pressure from online rivals. For J.C. Penney, that’s Amazon. For J. Crew and Neiman, it’s the likes of Richemont’s Net-a-Porter. The latter two are no laggards to online themselves, so this challenge should be manageable. Their capital structures, however, are proving more of a hurdle.

Some stronger groups, including Gap Inc., have tapped the credit markets. In the U.K., a number of retailers such as Asos Plc, have turned to shareholders. American chains may follow suit. But the steep falls in many retailers’ share prices may make that difficult.

A buyer also can’t be ruled out for Neiman or J. Crew, which will continue to trade after also reaching agreement on $400 million of financing. After all, both have recognizable brands. But with valuations uncertain, a rescuer can’t be counted on either.

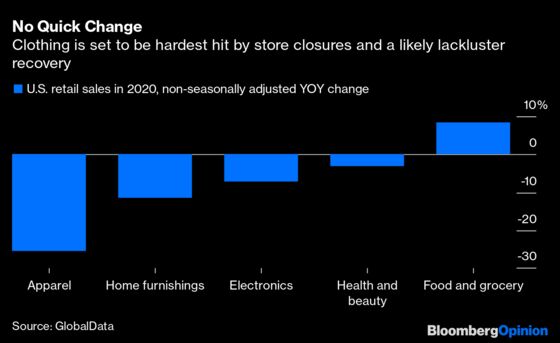

While the lockdown, and likely tepid recovery is most worrying for those companies with fragile finances, stronger chains will also emerge weaker. Gap, for instance, revealed that with physical stores shuttered, it would burn through half of its cash pile in less than two months, eroding its financial position at a time when it was seeking to revive its core Gap brand.

Gap had $1.25 billion of long-term debt as of Feb. 1, less than one times its Ebitda of $1.6 billion and seemingly manageable. But with the pandemic, cash reserves — which stood at $1.7 billion on Feb. 1 — have dwindled to an estimated $750 million to $850 million as of May 2.

After the struggle to survive, there will be little left over to invest, a problem when consumers are likely to be even more discerning and addicted to online shopping. So for those retailers that do make it through the crisis, prospering afterwards will be another thing entirely.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andrea Felsted is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the consumer and retail industries. She previously worked at the Financial Times.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.