(Bloomberg Opinion) -- When research firm GlobalData surveyed Americans on which stores they were most looking forward to visiting once the Covid-19 pandemic subsided, one household name came out near the bottom, and well below its department-store peers: J.C. Penney. That helps to explain Friday’s late news that the retailer — which began life in 1902 as a store called The Golden Rule — filed for bankruptcy protection. Pushed to the brink by the coronavirus shutdowns, J.C. Penney Co. was seemingly left with no other choice. But years of struggle and strategic missteps had laid the groundwork.

After securing $900 million of financing, J.C. Penney will stay open for now, and its next steps include closing some stores, cutting its debt by several billion dollars and looking at alternatives including a sale. Despite those planned survival efforts, it’s hard to see J.C. Penney having a vibrant future.

Even before the coronavirus crisis, the retailer, with just under 850 stores in the U.S. and Puerto Rico, had battled to be relevant to shoppers. Changing consumer tastes and incursions from online sellers wreaked havoc on its sales. And so now, unlike in the case of luxury department-store chain Neiman Marcus Group Inc., which also filed for bankruptcy this month, there may be little for a potential acquirer to pick up.

The downfall of J.C. Penney — a chain that grew out of a single store opened 118 years ago in Kemmerer, Wyoming by James Cash Penney — is part and parcel with the long, slow decline of the department store. The concept had its heyday from the end of the Second World War through to the 1980s. Often starting life downtown as Americans moved to the suburbs, these venerable names followed, opening in newly built malls. They focused largely on clothing and the items needed to furnish the homes that Americans were buying. Amid the age of mass car ownership, they were more than happy to drive to these retail attractions.

For many years, J.C. Penney was known as a family department store. If not somewhere Americans aspired to shop, it offered good value, and solid styles. In fact, it was a bit like Britain’s Marks & Spencer Group Plc, the sort of place you went for back-to-school gear and basics. But at least M&S sold food — because by the 1980s, the environment for department stores was already darkening. In 1988, Walmart opened its first super-center, adding groceries to its non-food selection to encourage more regular visits. At the same time Target Inc., another mass merchant that combined clothing, home furnishings and groceries, was quietly expanding across the U.S.

The mid-market, which J.C. Penney had traditionally occupied, was under attack, not just from discounters, but later the internet, which was rapidly displacing department stores as the one-stop shop, and with cheaper, more transparent pricing.

By 2011, in an effort to reinvent itself, J.C. Penney appointed Ron Johnson, an executive from Apple Inc. who built the tech giant’s much-admired retail network. Some of his ideas – a communal space in stores for yoga classes and coffee bars and food stands dotted throughout – were directionally right, even if they never got off the ground. Other concepts did come to fruition and were disastrous, such as ditching the coupons that had driven much of J.C. Penney’s traffic.

When Johnson was ousted in 2013, the company apologized to customers in a television commercial: “We learned a very simple thing – to listen to you,” it said in the ad. “Come back to J.C. Penney.” Unfortunately, they never did to the same extent.

While subsequent leaders Marvin Ellison, now chief executive of home-improvement chain Lowe’s Cos Inc., and current CEO Jill Soltau made progress, the company has yet to regain its stride. It has grappled with messy stores, and a lower proportion of online sales — around 20% — compared with 26% at Macy’s and 33% at Nordstrom.

Most recently, Soltau had cut discounting and reduced the amount of stock the chain carries. She also ditched the electrical appliances that Ellison introduced and sought to strengthen Penney’s core clothing offering. But her efforts, however valiant, were no match for weeks of stores being closed. The group was also burdened with net debt of $4.5 billion, including store lease liabilities of just under 8 times Ebitda as of Feb. 1. Penney said late Friday that it owed creditors $8 billion.

With the company less constricted by debt, it may be possible for Soltau to turbocharge her recovery plan, which already includes rejuvenating locations. A store in Hurst, Texas shows the way, with a much-improved layout as well as styling, cafes, a fitness center and a barber shop. Soltau insists it’s not a prototype, but with more investment freedom she may be able to inject elements into other stores. She also had already begun to pare back J.C. Penney’s store base. More locations will close, in phases.

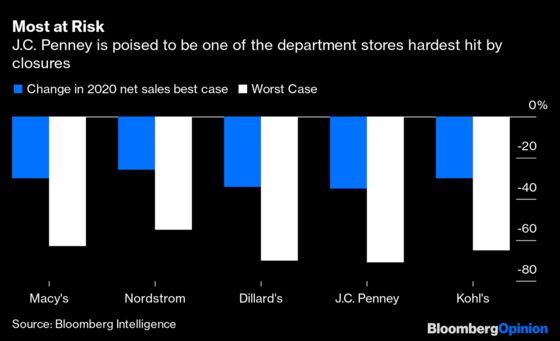

Stacey Widlitz of SW Retail Advisors estimates J.C. Penney’s footprint could shrink to just 150 stores. Even so, it’s hard to see how the retailer can stave off dwindling mall traffic if nervous shoppers stay home. Distinguishing itself from other mid-market rivals such as Macy’s Inc., which has its own plans for reinvention, will be another challenge.

A financial restructuring isn’t a panacea. For retailers to make it through such a process and flourish, there must be a revival of the operating business, too. It’s far from clear whether J.C. Penney — or any new owner — can pull that off.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andrea Felsted is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the consumer and retail industries. She previously worked at the Financial Times.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.