Fed’s 100-Basis-Point Shock Rate Cut Expects the Worst

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The Federal Reserve couldn’t wait 69 hours.

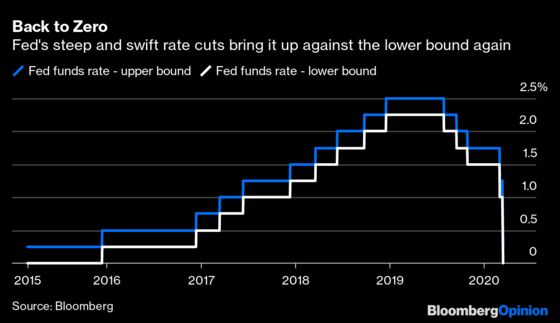

The fact that Chair Jerome Powell and his fellow policy makers took drastic action by cutting the central bank’s benchmark interest rate by 100 basis points to a range of 0% to 0.25% was bold in its own right. But to do it on Sunday, just days before the Federal Open Market Committee’s scheduled meeting — which it canceled — and less than two weeks after the Fed’s first emergency rate cut since 2008, conveys an added sense of urgency about the potential economic fallout from the coronavirus pandemic.

What’s more, the Fed announced it would boost its holdings of U.S. Treasuries by at least $500 billion and its agency mortgage-backed securities by at least $200 billion in the coming months. If there were any doubt about whether the central bank was restarting quantitative easing before, there should be no doubt now: QE4 is here.

The Fed appears to be making its decisions based on the adage: “Hope for the best, expect the worst.” It’s about all anyone can do in the face of a global pandemic. Here’s what the central bank had to say in its statement announcing the huge interest-rate cut:

“Available economic data show that the U.S. economy came into this challenging period on a strong footing. Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in January indicates that the labor market remained strong through February and economic activity rose at a moderate rate. Job gains have been solid, on average, in recent months, and the unemployment rate has remained low.

…

The effects of the coronavirus will weigh on economic activity in the near term and pose risks to the economic outlook. In light of these developments, the Committee decided to lower the target range for the federal funds rate to 0 to 1/4 percent. The Committee expects to maintain this target range until it is confident that the economy has weathered recent events and is on track to achieve its maximum employment and price stability goals.”

This is a tricky spot for Fed officials, who haven’t been shy about opining about what will happen when the central bank returns to the zero lower bound of interest rates. In general, there seems to be little appetite for taking rates below zero as they are in Europe and Japan, and Powell reiterated on Sunday that he doesn’t see negative rates as appropriate for the U.S. That means the Fed has taken its shot. All it can do now is wait and see whether the disruptions to everyday life for individuals and businesses will rise to a level that will force a new kind of unprecedented action (think yield-curve control) or if it’ll simply be a short-lived shock from which the U.S. can bounce back quickly.

Suppose it’s the latter. “I expect we’ll have a big rebound later in the year,” Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin said on Sunday. In that case, can anyone really expect the Fed will raise interest rates or pare back its bond buying as quickly as it eased in recent weeks? I seriously doubt it, which is why the central bank’s comment about keeping rates locked near zero “until it is confident that the economy has weathered recent events” sounds like wishful thinking. It’s been just more than four years since the Fed lifted off from the zero lower bound. Now central bankers — and bond traders — are back there much sooner than expected.

Lest anyone forget, there are significant political optics to moving interest rates around in an election year. President Donald Trump, naturally, said he was “very happy” with the Fed’s decision. Trump bragged about the stock market’s bounce on Friday, a fact that some observers suggested played into the central bank’s decision to move just before U.S. futures markets opened.

“The kitchen sink has been thrown, but there may be more to this,” Ward McCarthy and Thomas Simons at Jefferies LLC wrote. “Policy makers apparently wanted to take advantage of Friday’s late upswing to keep the market momentum going.”

That didn’t exactly go according to plan, with futures contracts on the S&P 500 hitting the limit-down band in the first few minutes of trading after the Fed decision.

Last week was full of nightmares for Wall Street, from the inability to find liquidity in U.S. Treasuries to resurgent fears of default and stress in the banking system after a swath of companies acutely harmed by the coronavirus planned to draw on their lines of credit. The QE4 bazooka should help quell those anxieties, as should the several measures the Fed announced Sunday related to the discount window, intraday credit, bank capital and liquidity buffers, reserve requirements and the U.S. dollar liquidity swap line arrangements.

Still, this is largely uncharted territory for traders, Fed officials and Americans in general. It’s not entirely clear that the traditional measures of monetary policy will be enough to jump-start — or even salvage — global economic growth. The Fed is proving once again it will do whatever it takes within its power to prevent the coronavirus outbreak from triggering a financial crisis.

But it can only do so much. Christopher Low at FHN Financial speculated that the Fed moved on Sunday rather than at its meeting because “expanded testing will mean a significant increase in the number of Covid-19 cases by Monday morning … NY now has the most known cases, but only because NY is testing most aggressively. As testing ramps up in other states in the next week or so, the number of cases nationally will rise proportionally.”

Things won’t just return to normal in the U.S. with this 100 basis points of easing. But the Fed has done what it can.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.